Considering icons of different music worlds: two eulogies

Maybe rewrite history and David Cassidy shows up late for the Partridge Family audition, stoned, hair plastered to his skull, so the next guy, Walt Strohman or someone, ends up Keith Partridge, and somewhere down the line Walt runs for President, drives into North Korea with a USA flag pin in his lapel. David Cassidy, well, let’s just say he joins the Peace Corps, gets a corporate gig, divorces, bangs up his knee in a hang-gliding incident, spirals sideways, slurping solo appletinis at Olive Garden. You get the idea.

But the moment David Cassidy became Keith Partridge, he became fixed as Keith Partridge till the day he died, like Elvis kept on having to be Elvis, and Chaplin couldn’t stop being the Tramp, penguin walking even unto Swiss exile. Twenty years old when he got the job, David-cum-Keith lived blessedly in a California cul-de-sac (I think), riding to gigs on the funky Mondrian Partridge Family bus.

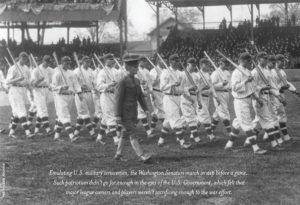

The bus was made for Keith—a proxy for America trying to outpace the Eisenhower suit, black-and-white tv. It’s hard to remember, but buses at one time were conveyances of transcendence. You know, not just sharing a smoke with a sad-sack in worn-out shoes, but Ken Kesey, Greyhounds to Montgomery, Fathead Newman blowing sax on the chitin circuit. To be sure, the Partridge Family was commodified, homogenized, Keith the epitomized product, the bus doubtless a product of much corporate dithering, but when the Partridge Family first aired, September, 1970, as school kids were getting back from summer vacations, maybe a school bus wasn’t just a school bus, it could be like an express ride to Valhalla. At the top of our lungs, my grade school friends and I sangshouted “I Think I Love You,” maybe it was, or “I Can Feel Your Heartbeat” or any of the catchy leave-nothing-to-chance Wrecking Crew tunes coming through the static on those waning summer days. David Cassidy/Keith Partridge with his earnest sloe eyes and hair like a fashion-forward Jesus’ had come to carry us to salvation. We were ready, willing, rapturous.

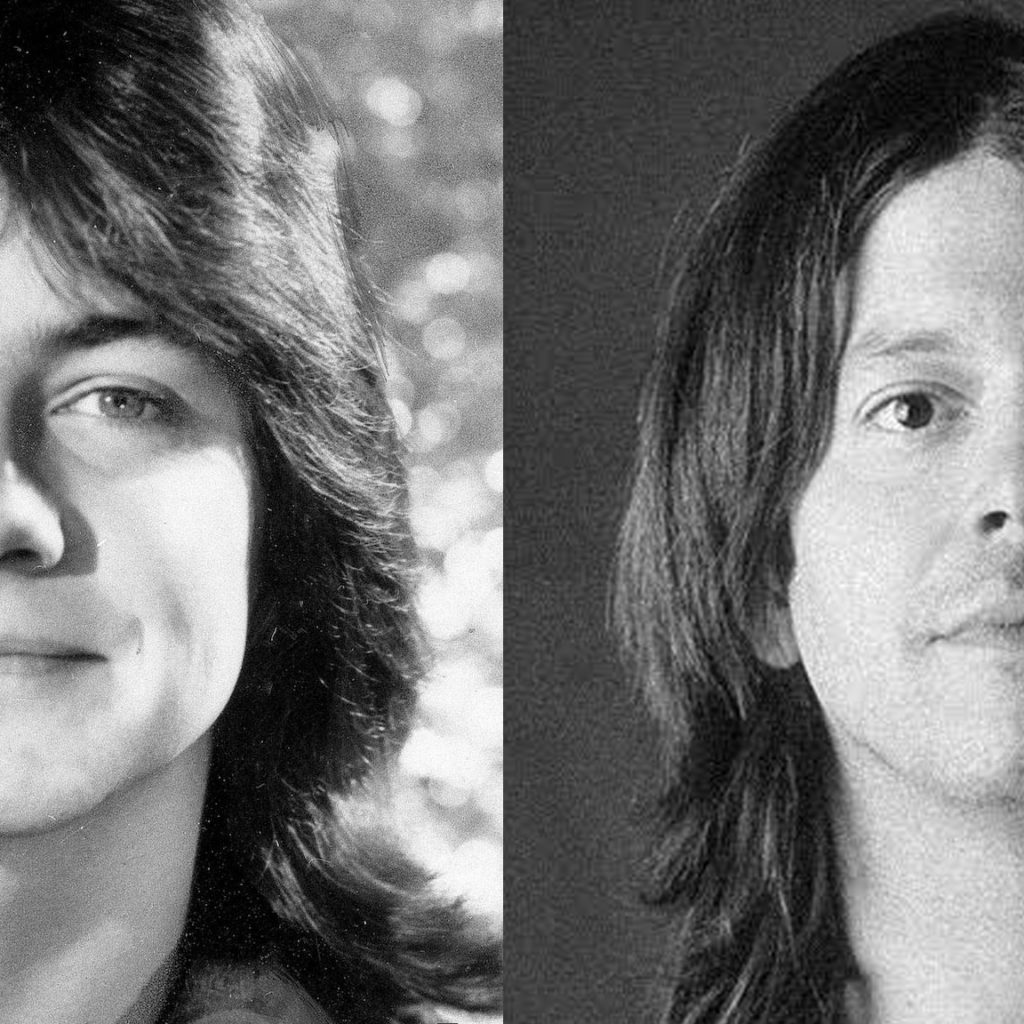

Grant Hart, songwriter/drummer in the seminal punk outfit, Hüsker Dü, died a week before David Cassidy—in comparative obscurity. I didn’t even learn about his death (liver cancer, Hepatitis C) till months after the fact. But like David’s, Grant Hart’s life would be summed up from a brief intensely packed period in his twenties. From 1979 to 1987 Grant sang from behind the kit like Gene Krupa and Judy Garland on everything, bare feet pumping the bass pedals, hair whipping off halos of sweat. Hüsker Dü had aspired to be punk rock’s answer to the Beatles, and succeeded to the extent that the band was once interviewed by Joan Rivers; but they never became the Beatles, or U2 or Culture Club for that matter. After the band’s inevitable breakup in 87 Grant, for all his vividness, became a cautionary tale, living a mashup afterlife of semi-addiction, puttering with classic cars, painting, sliding in and out of the alternative rock scene, releasing an underappreciated album here and there. Maybe some of us will always be ourselves, vectors of our genes’ power over us, while others are irrevocably exponents of chance. There was probably no alternative life for Grant Hart. Winning the lottery, a hang gliding incident, wouldn’t have knocked him off the course he was on.

People often assume, I think, America was pretty radically made over in the time between the cancellation of the Partridge Family tv show in 74 and the release of Hüsker Dü’s first album (Land Speed Record) in 81. But who knows, maybe things didn’t change that much. In the early 70s, tuning in Cronkite, helicopters cruising over Vietnam jungle, the choppers’ whack-whack contrasting to my bicycle chain’s metallic whirl as I pumped across neighbors’ lawns in suburban Massachusetts, optimism was still the default American mode. In time Vietnam ebbed, the choppers lifted off the embassy roof, and Reagan’s sunshiny jingoism creeped into the living room, the bedroom, the boardroom. USA! USA! Hüsker Dü was only one of the bands that signaled the 80s flowering angst, twists of irony, a counter to the optative mood, but the band also germinated its own sense of precarious hopefulness. Listen to “Celebrated Summer”—and tell me it doesn’t knock you into a state of anguished ecstasy.

You don’t have to be a soothsayer to discern the consistent currents flowing beneath changeable surfaces. It was the 80s. I was exploring different directions in music, literature, movies—chasing the highbrow in a suburban middlebrow way. I graduated college, hitchhiked around, moved to Hawaii to complete the novel I’d been working on, wrote some poetry, moved to Brooklyn. Sometime in the midst of this perambulating, I scrounged tickets for a Hüsker Dü show in West Hartford, Connecticut. The show was toward the end of the band’s run, but on stage, pounding his drums, Grant didn’t appear to be running out of steam at all. He wailed “Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill,” “Don’t Want to Know if You Are Lonely,” full-throatedly, mop hair whirling. I pogo’d like crazy in the front row. The crowd sang along in tribal solidarity and, so it improbably seems, joy. It reminds me now, in David Cassidy’s and Grant Hart’s coincidentally linked deaths, how we did sing in our collective euphoria, preteens and punks, without exclusionary pretense, and lived for those moments of pure aural bliss, living for the tunes, as if no other utterance could possibly add to the divine nonsense of being.