Turn it up. When rock’n’ roll was punk, and the search for meaning in the mosh pit.

As the recognizable form, rock’n’roll came from out of seemingly nowhere and seemingly everywhere, organic but commercially driven, inevitable and accidental, it derived from prison hollers, English and Scottish ballad singing, Brill building song sellers, the invention of the transistor, the Arkansas hoedowns, shoeshine singers, Louisiana radio shows, West African gourd instruments, the chitlin circuit, the slave spirituals, medicine shows, minstrel shows, Mississippi riverboat dance band shows, zippos, sheet music emporiums, teenage grooming, backseats of cars, the speakeasy and cathouse stride players, homemade guitars, Yiddish theater, vaudeville and barbershop quartets and Camptown Races Do-da, and in the conforming hoopla of post-World War II atmospherics it was celebration of the democratic, the expressionistic, the subversive, it was music infused with race and identity politics, with the sublimation and distortion of race and sex, with urban and rural beats, Memphis, Chicago, Fort Worth, Clarksdale, and it spoke of depths of metaphysical sublimation and hunger, an anguish to feel, a barely articulate articulation. When Chuck Berry sang,

Swing low, chariot, come down easy

Taxi to the terminal zone

Cut your engines and cool your wings

And let me make it to the telephone

he wasn’t just singing about an airplane trip, he was mixing old spiritual longing with the modern condition, a sacred and secular conflation that warped the flight metaphor into something like a Ginsberg or Ashberry poem. Or when twenty year old Elvis Presley, a semi-employed truck driver, wandered into Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios in Memphis, and changed the course of popular music by singing,

Now this is one thing, baby

I want you to know.

Come on back and let’s play a little house,

And we can act like we did before.

Well, baby,

Come back, baby, come.

Come back…

you got the sense a lot more was at stake than doing the dishes. The universe was going up in flames, metaphysically, and Elvis (and guitar player Scottie Moore, and bassist Bill Black) was trying to keep time. Love, lust, have probably been standard song subjects since the first caveman whistled, but here was something extraordinarily combustible, menacing even, in the drawn-out syllables, the yelps and canine moans, against the cultural backdrop of all those Eisenhower-era teens sipping Coca-Cola by backyard pools. Little Richard and Elvis had been approximate hit-making contemporaries (“Tutti Frutti” entered the charts in December of 1955, “Heartbreak Hotel” was January 1956) and they would soon be followed by Jerry Lee Lewis, whose version of “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Goin’ On” was released in May of 1957, as Dwight Eisenhower, in the tentative but definitive first steps in dismantling Jim Crow, was sending troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, guarding African American students walking to an all-white high school. The optics for both Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard in 1957 must have been, let’s say, less suited for prime time living room watching than those of the comparatively mildmannered Elvis. But take a look at old pictures and video clips on Youtube of Richard and Jerry Lee from that era: even they were performing in suit and tie, their fashion sensibilities more in line with Steve Allen and the Anita Kerr singers than later gaudily spangly presentations of themselves, or—across the looming generational divide—the likes of Hendrix or the Beatles. The Beatles themselves were a uniformly mod-suited lovable combo in 1963, the year of “Viva Las Vegas” and the John Kennedy assassination, but within two years they’d morphed into the nascent drugginess and sitar experimentations of Rubber Soul.

By his mid-thirties, Elvis, for all his suggestive hip swivels and hair product provocations, had pretty much become relegated to the musical equivalent of the VHS, his endless string of mediocre movies undermining the otherworldly quasar of his early success. So old fans—now parents with jobs and mortgages, who viewed Elvis as a nostalgia-circuit figure of their own recently passed youth—must have taken notice of the television special comeback he mounted in 1968, performing in front of a live audience for the first time in seven years, hitting the stage in a black leather getup that made him look more like 50s-era Brando than the Beatles of their Sergeant Pepper resplendence, but belting out his repertoire of hits as if rediscovering the versatility and lusty clout of his own voice. His self-aware jokiness and leather outfit may have been unsuited to the flowing au current counterculture Beatles and Stones style, the hippies and Vietnam war protests going on in the streets, and it would soon lead to his arena-ready jeweled jumpsuit- and cape-wearing karate kicking excesses, but in 68 he’d staked out his territory and was pushing it for all it was worth. By that time, everyone was just trying to hold on, find their place. Chuck Berry’s

We had motor trouble that turned into a struggle

Halfway across Alabam’

And that ‘hound broke down and left us all stranded

In downtown Birmingham

was becoming Dylan’s

God say, “You can do what you want, Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’, you better run”

Well, Abe said, “Where d’you want this killin’ done?”

God said, “Out on Highway 61”

As with literature and the visual arts, no small part of the pleasure one derives from popular music comes from its predictable patterns, and its rejection of predictable patterns, the considerable feat of turning specificity into essentiality, the familiar into the wondrous. It’s an explicitly devotional move, implicitly political. One mission of art— maybe its primary mission, I have been thinking lately—is to declare life at its most quotidian to be to be unknowable, and then leaving it to the art to furnish its own particular meaning (whether a nonsense war whoop of “Tutti Frutti,” or Halley’s Comet arcing overhead in Giotto’s blue night sky) that has the effect of summoning the dead. It’s rebellion against any existing backdrop, a challenge to prevailing metaphors.

One problem with this idea—of art as rebellion—however, as Elvis et al must have eventually figured out, is that it has a limited shelf life. Defiance of norms in their context is one thing, but a few hundred years on, out of context, who really cares much that Candide is satire of enlightenment teleology, or thinks about Bach’s subversion of Calvinist musical norms? Maybe music or social historians know that “Tutti Frutti” superseded previous modes of expression, but after a while we’re left with the expression only. The context for the rebellion is an unread footnote.

The point is: rock music especially has always relied on the energy of subversion to counter the condition of existential ambivalence. Little Richard’s whoop, the giddy Chuck Berry lick in “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” (originally brown skinned), the siren whistle of “Highway 61” accomplish similar work: tearing down what gets in the way of feeling, foregrounding immediacy. Soon after the relatively innocent tunes of Little Richard, Jerry Lee, Buddy Holly et al began coming over the airwaves in the US and circulating transatlantically to England and back again, teaching the music of America back to itself, the songs, as a shared collective stock, took on more complex, and archly literary, forms. The LP album became the standardized format for serious artists. Hallucinogens, a thriving street culture, political vangardism, raised the ante. The music that came out of this period wasn’t so much in rebellion against the old as it was vaguely indebted to it. As curators, these bands were also going back past Elvis and Little Richard to deeper roots (Robert Johnson, Elmore James, the Carter Family, Charlie Patton, Bob Wills, Son House), averring prayer and nihilism in equal measure. And like kids who’d parlayed relatively modest inheritances into fortunes, the Stones, Beatles, Velvet Underground, the Stooges, Hendrix, the Who expanded their economies, amping everything up. Then when I started going to rock concerts in college in the 80s, you stood, as a test of good faith, as close to the stage as you could get, elbowing and leaping your way into of the arms of strangers in the madness of what would become known as the mosh pit. Bands like the Replacements, Ramones, the Lyres, Pogues, Sonic Youth, the Cramps, Leaving Trains, Lazy Cowgirls, Jason & the Scorchers, Hüsker Dü, Black Flag played at such frenzied speed and volume that you were compelled by the music’s sheer force to release yourself to it, part of the frenzy you were creating. I wasn’t a drug user, but this must have been something like what it was like: feeling the power of absolute surrender. That I also happened love Frank Sinatra, Patsy Cline, Chuck, Elvis, Buddy Holly, Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen, may have put me at odds with many dorm-mates and fellow concertgoers, but the broader musical repertory spoke of some expanded tribal attachment, each concert creating a portal into the history of everything.

A question occurred to me the other day. What was one supposed to do with that elevated feeling engendered by these experiences? It’s an odd question. I’m not sure it makes as much sense as I think it ought to. Either way, I don’t have any answer for it. You sing along. You feel, in the general sense, as Emerson—the transparent eyeball—proposed, being “glad to the brink of fear.” When you look at a Rembrandt it doesn’t so much demand viewers stand on any cliffs as it asks them to consider eternal stillness. But of all artistic genres, rock music in its purest form seems to call one to action. When Shane MacGowan, frontman of my all-time favorite band, the Pogues, sings,

Now you’ll sing a song of liberty for blacks and paks and jocks

And they’ll take you from this dump you’re in and stick you in a box

Then they’ll take you to Cloughprior and shove you in the ground

he’s implicitly enjoining us to witness and acknowledge suffering, ugliness, hopelessness, the grit beneath your skin, and—at least that’s how I see it—to stake a position. For those of us who grew up in the mashup decades of the 70s, 80s, 90s, going to see these bands that played with high-wire exhilaration, we felt gladness to the brink. We were true believers.

But to get back to my original question: What’s the point of rock music? Or is that a bad faith question to begin with? Is all that thrashing about, the ramped-up guitars, merely entertainment, a pose, a schtick, and one should no more expect music to have a point than Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, or Survivor? Yet— Yet a few answers might be suggested. 1) More is the point. Turn it up. Little Richard’s band used to play through a 25 watt PA. A decade and a half later, the Who’s PA was 120,000 watts. You can’t hear your own thoughts. You’re lost in greater and greater waves of sound pressure pushing your cells around. But volume on its own, it seems to me, points to diminishing returns, lack of meaning, the collapse of a tulip economy. 2) In its superficial disdain for mainstream materialist culture, rock, like hip-hop, also proposes an alternative materialism. Rebellion as a currency of capitalism. Graceland as the promised land. Take the Car, for example. Next to the Girl, the greatest of all rock metaphors. In fact, the first rock’n’roll song might have been “Rocket 88” (1951), Ike Turner’s paean to a new model Oldsmobile and a template for practically everything that came after: Chuck Berry, songs from Janis Joplin, the Beach Boys, Springsteen, Prince, A Tribe Called Quest. The car, like the girl, evolved as a metaphor of conveyance, of escape, transcendence, of motion as emancipation, but it’s also a capitalist motif, and rock’s adoption of it complicates the notion of rock as rebellion against the larger social milieu. Monthly car payments warrant no mention in “Rocket 88” nor “Little Red Corvette” nor in any of Springsteen’s epics of escape and survival. 3) Though much—most—of rock music isn’t overtly political, it can, in its prevailing tendency, make the political point that the world, being fraught with anxiety, insecurity, turmoil, is always looking to be upgraded. Rock music, like the church, inches toward salvation. Art does shape our way of knowing, our way of seeing the world outside itself, and making the unknowable into, well, not exactly something knowable, but perhaps tolerable. At any number of the Pogues concerts I went to over the years, Shane would lurch into the line from “Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” “They’ll take you from this dump you’re in and stick you in a box,” and the instant had the effect of bonding the tribe—the world, it seemed to me—in humane solidarity, intersecting anguish with hope before they take you from the dump. Perhaps, in retrospect, there’s a moment, thinking of such nights, when you find yourself unexpectedly responsive to the music’s accumulated force. That’s all.

The other day I was talking to my lifelong friend, Eve, who told me a story about being on hold with customer service at Neiman Marcus, when the wonderful pop confection “Can’t Hardly Wait,” from the Replacements’ Pleased to Meet Me album, came on.

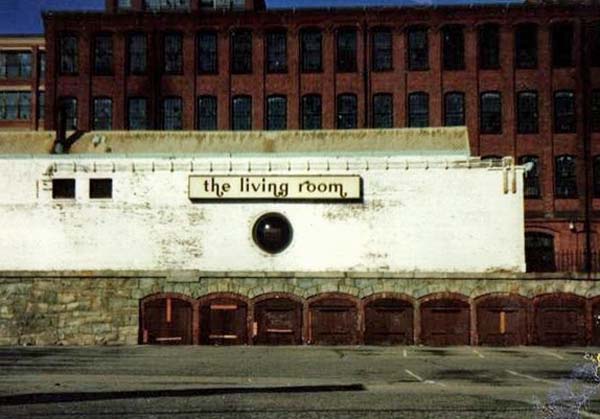

Eve and I had seen the Replacements together in Providence, in the late 80s, on a memorably debauched, wondrously cinematic night that’s remained a mythical touchstone for both of us lo these decades later. If my memory is right, the Replacements’ original guitarist Bob Stinson had been kicked out of the band and they were touring in support of Pleased to Meet Me, on the cusp of a commercial breakthrough that never quite happened. Without Bob, they were a more professionalized unit but still careeningly unmanageable. At the time I wasn’t tuned to the band’s looming identity crisis, but it hardly mattered; the Living Room in Providence, like CBGBs in the Bowery or a million other rock clubs across the country, was graffiti scribbled, possessed of a reassuringly ambient stench of cigarette smoke, b.o. and sloshed Budweiser, and Eve and I, caught in the room’s dim strobe flicker, surfed the wave of elbows, shoulders, the sudden intimacy of a stranger’s mouth two inches from your face. All these decades later discreet memories of that night still exert a stranglehold on my imagination, and I wondered if the Neiman Marcus folks, or the hold music folks, could have fathomed the song’s meaning (that absurdly inadequate word) to us. Or had “Can’t Hardly Wait,” sunk into the generational background, as “Tutti Frutti” or “Heartbreak Hotel” in our parents’ generation had a few decades before: a noise that elicited a fond echo, with little trace of its original tumult and insurgency.

“Can’t Hardly Wait” is a love song of love in tatters, as much of an anthem as the Replacements could ever muster, a pop ditty with an ashtray heart. For a band that so famously shrugged its shoulders at commercial considerations, it’s a wonder the Replacements themselves could have ok’d the licensing of the song, or that the lyrics passed Neiman Marcus’ corporate muster:

Jesus rides beside me

He never buys any smokes

Hurry up, hurry up, ain’t you had enough of this stuff

Ashtray floors, dirty clothes, and filthy jokes….

But maybe that’d been the point all along. In begrudgingly joining the mainstream, the music was less corrupted by its association with it than the mainstream was enriched by the music. Songs like “Can’t Hardly Wait” are secret bombs waiting to go off, insisting, as you’re on hold at Neiman Marcus, that life’s a messier business than you think, but we’ll get by in defiance and, as Emerson says, gladness to the point of fear. Or, as Shane MacGowan in his cigarette-and-god-knows-what-abraded voice, sings, “Then they’ll take you to Cloughprior and shove you in the ground/ But you’ll stick your head back out and shout, ‘We’ll have another round.’”