Annals of weird old America: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln & its strange aftermath.

On a cool April evening, after a dinner of cornpone and chicken fricassee, a small group—two couples, a generation apart—set out for the theater in a lacquered two-horse carriage. The women swapped little stories, fluid and familiar, while the men talked of peacetime things, farming, trains and such. The mood was just short of jovial, a neighborly parry of frontier talking, quick jabs of consonants, vowels wind-blown. The group included Clara Harris, glam socialite daughter of a New York Senator, her fiancé Major Henry Rathbone, and Mary Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln. In the carriage, rubbing the night’s slick mist from his face, the president tried out a couple new jokes. You could hear a creak when he stretched his legs. Long bones growing wintery. Henry Rathbone laughed extra hard at something Mary said. Really—the way Clara held Henry’s hand— It was Good Friday. Portents had given Abraham Lincoln grief in the past, Shakespearian, Talmudic caliber visitations of sailing at great speed—wine-black waves—but tonight he was having none of it. Not even a week had passed since Grant and Lee’s war had sputtered to an end at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, some hundred and sixty miles to the south. In the District, bells had tolled for the victory. Shattered men crutched along E Street. Mothers, widows in their weeds, made their way down Massachusetts Avenue. Tonight was for respite.

The experience of a single death unanticipated by old age, cancer, a faltering heart, has to be pretty close to universal. The soul-deep stabbing of grief, the inconsolable reflex of denial, the body’s physical revulsion, a realization of life’s chilly caprice…. In this regard was Lincoln’s death on this April night at Ford’s Theater so different from any other unexpected death? The facts of the night are part of national collective memory. We need hardly review them: the’s assigned guard goes out to a bar. The famous actor, J Wilkes Booth, familiar to the theater, presents his card to an usher— He climbs the stairs to the presidential box, and enters— Barricading the door—Drawing the derringer. The shot. Mary Lincoln screams. Blood on pretty going-out dresses. Booth slashes a dagger to fend off Major Rathbone, severing the major’s artery, then bounds off the presidential box onto the stage, breaking his leg. A born overactor. He wields the dagger like Macbeth contemplating its existence, and declares, as far as we know, Sic semper tyrannis, or some similar phrase you imagine him rehearsing in his head over and over. With a fractured fibula (conjecture as well, your honor—), Booth eludes about a dozen men trying to stop him, he seeks open ground like a fullback, mounting his waiting horse, and riding off in the gray drizzle, a blurred horseman. Actress Laura Keene makes her way into the box, cradling the president’s head in her lap while doctors, actors, stage managers, detectives swarm the place. It’s been thirty seconds, a minute, since the actor put the derringer to the back of the president’s head. Playgoers stream into the street. Lincoln’s carried to a border’s bed in a nearby house, diagonally situated because of his height, and in the ensuing hours is attended to by caretakers helpless to do more than watch, mutter in and out the door, swallowing grief.

April 15

It’s over. 7:22 this morning. You’d think with four years of unremitting killing there’d be no headroom for lamentations, but the president’s death, announced in every daily throughout the Union, signaled a new kind of mortifying clarity. Appomattox had been a false ending—

In the days after the assassination, the Confederacy still existed in theory, but was in shambles. In North Carolina, soldiers were deserting the Army of Tennessee by the thousands, the remnant simultaneously fending off Tecumseh Sherman’s forces and negotiating terms of surrender. On the run, Confederate president Jefferson Davis operated a shadow government out of a box car, lugging the treasury’s gold in wooden crates over half of Georgia and the Carolinas. Meanwhile on the night of April 23, Booth rowed across the Potomac into Virginia, nursing an increasingly painful leg. In this area, he was a known quantity, a celebrity. Swaggeringly handsome, a relatable, contemporary type, with a volatile heightened profile—Johnny Depp, Hugh Jackman. Relying on an old Confederate secret mail route, he and accomplice David Herold, a pharmacy clerk, disguised as best they could as Confederate veterans, tried to make their way deeper South.

April 21

“Carrying a corpse to where it shall rest in the grave, Night and day journeys a coffin,” wrote Whitman. Lincoln’s funeral train wended along 1700 miles of track toward Springfield, stopping along the way: Harrisburg, Herkimer, Buffalo, Erie, Indianapolis, Joliet— Such conspicuously American sounding place-names! Black crepe had replaced the patriotic bunting of the previous week, hanging from every storefront and counting house. Rocking through the night, the train came upon bonfires, torchlights— otherworldly stabs of light in otherwise prairie darkness. Massed voices singing, “Farewell Father, Friend and Guardian.”

Not only had he presided over the Civil War, but Lincoln had given its military exigencies a political, rhetorical, moral shape, transforming tableaus of summer marches, the smashed, eviscerated bodies in mass graves, into something resembling a classical tragedy. The Second Inaugural address, a valedictory delivered on a frigid March afternoon a little more than a month before the assassination, set him and his political agenda up for national transcendence. “With malice toward none, with charity for all….” Whitman too picked up on the benevolent mood, casting the “varied and ample land, the South and the North in the light, Ohio’s shores and flashing Missouri” in poeticized unity.

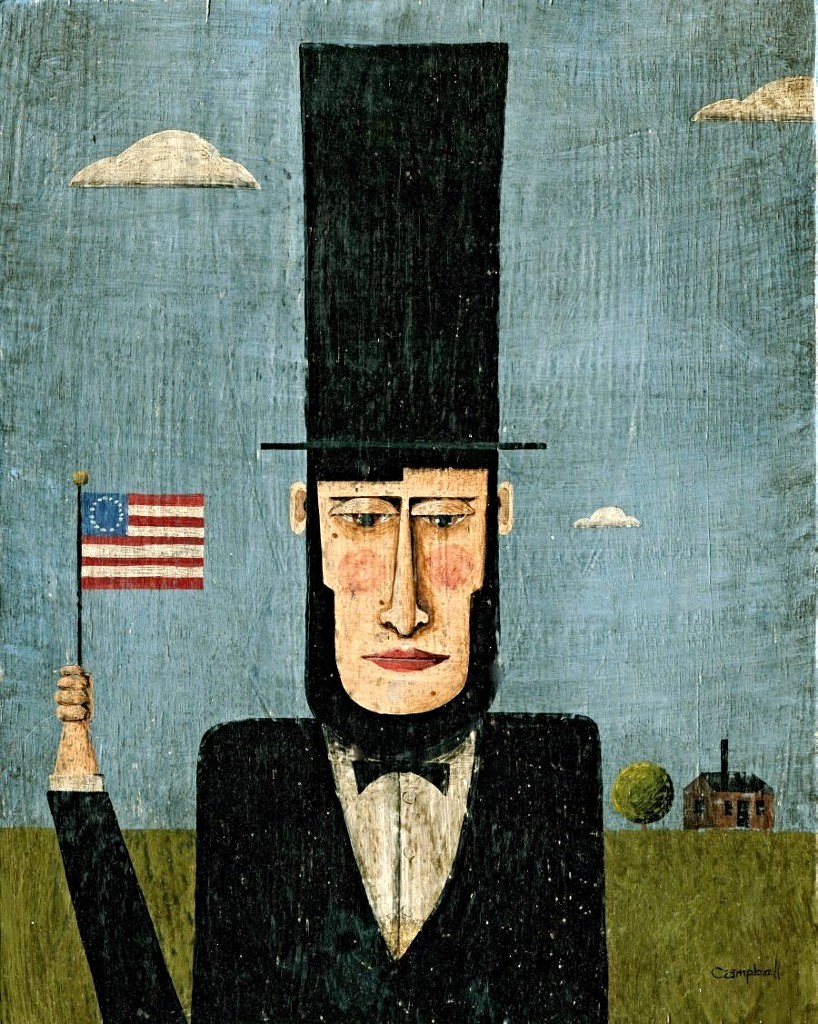

It’s impossible to know the extent to which malice toward none would have functioned as actual policy—it’s a tough sell in light of the national calamity of Reconstruction—but Lincoln possessed a probing adaptability to shifting meanings, subtle and not-so-subtle (a gradual emancipationist, he’d taken nominal Union victory at Antietam Creek in September of 62 to articulate the war’s ultimate meaning, and compelled emancipation to the foreground of the war’s aims). In photographs of him delivering the Second Inaugural on the steps of the just finished Capitol, with Booth in attendance, we see him bent forward, intent on the page in his hand. It’s the bearded, haunted, disembodied, visage of our dreamlike imagining of him: the one of the common penny, Rushmore, the fiver. He might already be dead.

But yet— Yet— In 64 Lincoln barely mustered enough votes to win a second term. The victory came mostly thanks to the states’ introduction of absentee voting, besides the votes of furloughed soldiers, and news of Tecumseh Sherman wrecking his way through the Carolinas. In his first term he’d been ridiculed in the press as bungling—a laughingstock to doyens like Henry Adams, who saw in his “plain, ploughed face; a mind, absent in part… above all a lack of apparent force.” But even Wilkes Booth lived long enough to confront the folly of this underestimation. Instead of being hailed as a Confederate Cassius, as he’d expected, Booth had been chased to the end of his line, and instead of triumph, found only condemnation. Lincoln’s death was, “the heaviest blow which has fallen on the people of the south,” wrote an editor on the Richmond Whig. “And why?” Booth scribbled in his pocket diary as Federal troops sought to flush him out of his hiding spot. “For doing what Brutus was honored for.… And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

April 26

Shortly after midnight, acting on tips from locals, twenty-some members of the 16th New York Cavalry canter up to the Garrett farm, outside Port Royal, Virginia, and set up a cordon around Booth’s hide-out. There’s no textbook for taking prisoner a presidential assassin who’s hiding out in a locked tobacco barn with a cache of weapons, any more than there’s a textbook for the assassin who’s hobbling about the barn with one good leg, calculating chances of a Wild West escape. But when the troops surround the barn, and demand Booth and Herold’s surrender, Booth offers the soldiers a deal—a duel at fifty paces—a last-ditch stage show for posterity, the only plausible result being that he’ll be gunned down in his own play, a showy martyr to the cause (the “Cause” had yet to be lost, Lost Cause yet to be articulated as Southern raison d’être) living on in posterity. The detachment’s commander demurs and orders the barn set on fire. Herold emerges, hands up. Booth, carbine rifle against his hip, tauntingly remains. A sergeant with the notably extravagant name of Boston Corbett had earlier volunteered to go in and fight it out with Booth in the barn, mano-a-mano, but now Sergeant Corbett takes aim at the flickering figure behind the barn slats, and squeezes the trigger, felling Booth. Heat presses the men’s brows and beards, they go in and drag the fugitive to the Garretts’ porch, a specimen pinned to a board, the matinee idol mustache wet with snot. Sunlight’s coming up, laundering the night air. The barn’s reduced to persistent embers and a tangle of burnt machinery. By now neighbors, curiosity seekers, tramp up through the morning light to join the vigil, hanging around in hopes of witnessing close up something that will get remembered, people will talk about and say they were there when of course they weren’t. It’s an hour, two, before the man stops asking for water, his breathing going shallow, then, finally, his eyes like dried river stones staring into the new day.

Booth’s desire to slay a tyrant and possibly become himself a Confederate martyr was inverted in apposite cruelty. In killing Lincoln, he’d achieved a measure of eternal notoriety that his acting, however popular in its time, had zero chance of bringing him, leastwise eternally. But in his last minutes he must have come to understand the irony that he was forever subordinate. His name would never be mentioned again without reference to Lincoln. Thousands of schoolchildren every year visit Ford’s Theater. The Garrett house collapsed into rubble decades ago, there’s a scant sign on the median between the northbound and southbound lanes of US 301.

Postscripts:

Four days later Lincoln’s funeral train reached Springfield. The bodies of the president and his son Willie, who’d died of typhoid three years earlier, were interred in a hastily constructed vault in the Oak Ridge Cemetery on the outskirts of town. Five days after the burial, Jefferson Davis and his reduced entourage, running out of places to run, cross the Ocmulgee, near Irwinville, Georgia. They stake up their tents by a little creek, gypsies, wayfarers, disguised exiles. The Federal authorities, in the form of the 4th Michigan, 1st Wisconsin, are a few miles behind. Cavalry. Wild azaleas, buttercups, foamflower, are in bloom. Night calms the buzzing of the honeybees. Before dawn a smatter of rifle fire comes cracking along the creek, and Davis, bone tired of running you’d guess, unbends out of his field tent. Stooped. Maybe a little nearsighted, trying to find spectacles. His face gone whiskery. Taste of recent tobacco in his teeth. He runs—a few yards toward the creek. And realizes—

For the next two years he lives like others—biscuits, water, pacing the parapets of Fort Monroe. Indicted for treason for which he’ll never stand trial. He’d been at this fort before, as Secretary of State, President of the Confederacy, an understated leader of men, his name blooming in fireworks in the night sky.

It’s July now. July in the District, in the courtyard of a prison. Miasma blankets the Capital’s marshes and lowlands. Heat settling in for the duration. You could get tickets for the hanging if you were lucky. Best if you remembered a parasol though. Booth’s associates—the conspirators—struggle up the scaffold stairs in the courtyard, helped to their seats by a courteous hand. Their feet and hands are bound. David Herold, Lewis Payne, Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt. These things happen with a speed that feels unjust. The order for their execution is read, and the heads duck forward to receive the hoods, they are led two steps forward to the trap doors, a scent of new lumber coming through the hoods. A pair of hands claps, the doors swing down, the bodies jolt, swing, settle. But the living men and woman twitch, some in the crowd turning away, some starting to register. There’s been a miscalculation. It takes minutes for the ropes to press the air out of them. In his vaulted cell less than two hundred miles away, Jefferson Davis wonders about his own fate. “President Johnson,” he says, “is very quick on the trigger.”

Postscripts. Postscripts. In America, postscripts have this antic quality of the high grotesque, don’t they? Pathos mixed with a hoot. Meaning drifting into the weirdest corners. One Boston Corbett, high on mercury nitrate, mad as a hatter, drifts in and out of the nineteenth century’s chugging milieu, a quasi-mystic who’d come after you with his fists, pistols, for saying hell, resolutely parted hair and a madman’s eyes. Approached by prostitutes, so as not to be led unto temptation he cut off his testicles with scissors, a eunuch preaching on a soapbox. For a while he toured churches, little theaters, with lantern shows of the scene at Garrett’s barn. He mimed his aim. It didn’t have to be Boston Corbett who shot Booth, it could have been Private Smith, Corporal Jenkins, but it’s Corbett the zealot who signifies the ambient madness of the times.

More postscripts. Colonel Henry Rathbone survived Booth’s dagger to marry Miss Clara Harris, his ringletted step-sister (you heard that right— step-sister). Seventeen years after the assassination, president Chester Arthur appointed him Consul to the Province of Hanover, Germany. Then one morning, increasingly prone to delusion (it had been a problem for a while—), Consul Rathbone drew a pistol on Clara, who’d been in bed, killed her, and in should-be-but-isn’t droll replication of events at Fords Theater, stabbed himself over and over. Committed to an asylum outside Hildesheim, the Consul lived out his days, another madman pacing the asylum.

One last. Too good to pass up. In 1903 a theatrically inclined housepainter, David E George, claiming to be John Wilkes Booth, borrowing the actor’s infamy, ended it all in a locked hotel room, with a dose of arsenic. For a few years the housepainter’s embalmed body sat in the window of a mortuary and furniture store in Enid, Oklahoma, nattily attired, reading the day’s newspaper, advertising the establishment. This is true. Look it up. Eventually an enterprising carnival impresario who’d known George purchased the mummified body, taking it on the road alongside bearded ladies, three-legged men, propping it up as the man who killed Abraham Lincoln. There’s a resemblance. The mustache. The chin. And you can imagine George’s posthumous satisfaction at being represented as Booth. For more than five decades the mummy was packed in and out of steamer trunks; then by all reports it vanished sometime in the 1970s. Mummified assassins, real or otherwise, probably held little cultural currency in a tv-saturated landscape. But how it was that David E George and John Wilkes Booth might have been one in the same hints at something more than a bunch of willing dupes plunking down their nickels to get a gander. The story had it that Andrew Johnson had orchestrated Lincoln’s assassination. It wasn’t Booth killed in Garrett’s barn back in 1865 but someone else. A patsy maybe. While Booth, of course, lived on as David E George, painting houses, doing bits of Lear and MacBeth for the locals, until making a comeback as a sideshow oddity. The story hints at shady propositions so unlikely there’s no question about their authenticity. Sergeant Corbett was in on it too.

Democracy tells us, not-so subliminally, to pursue our own mystic dreams. Since, say, the Salem trials Americans have been fantasizing about dark forces, secret cabals, information passed in alleyways. The deep state. Some broodingly underground, unhinged version of American life. Sometimes it’s a wonder that the nearly unelectable Lincoln of 64, stumbling and inconsistent, losing a misbegotten war, ever got any credit at all. His earnestness was the most foolhardy posture in history. Then Booth’s .44 caliber bullet started in motion the sanctification of the man he hoped to obliterate.