The Klan in my backyard.

Childhood is the entertainment of the improbability of an ending, plus an ongoing instability of the moment. When I was a boy growing up in Sudbury, Massachusetts, at five, six, seven, I believed, probably like lots of kids that age, in the commonplace of the miraculous, the likelihood of coincidence, the inevitability of imaginative truth. That’s to say, if I composed a letter from an ostensible pirate in blood-mimicking red ink, complete with treasure map, such a pirate must indeed have existed, swashbuckling through my backyard in some distant epoch. If a time machine could be conjured out of twigs and old cereal boxes, I was, voila, transported to some Civil War battlefield, or reassuringly tragic Viking langskip. A bliss of free association prevailed.

In this once-agricultural now suburbanized colony of Boston, childhood was good. Or anyway, on the little side street we lived on there wasn’t a lot of cultural data to agitate for a conflicting perspective. It was the Sixties in high season, and the anti-war protests, the Freedom Summer, the blown-up churches, the dead kids, the assassinations, Woodstock were in full bloom, yet the Sixties as historical moment occupied only the extreme periphery of my childhood attention, and, as far as I could tell, the attention of the adults around me. Only glimpses of Time magazine pictures of Martin Luther King, My Lai, or the novel wardrobe choice of a formerly orthodox mother, hinted at the world at large. We were—the Cards, our Eddy Street neighbors, the neighborhood kids—safely, homogeneously, white, mainly anglo, aspirantly middle-class. To the kids of young parents—my peers—the draft was hypothetical. The violence gutting the American South might as well have been taking place in Timbuktu. Woodstock—it was something a friend’s uncle had come back from with a different girl than he’d gone with.

Neither did history make much of a dent. A decade or so after the Second World War, in a second spasm of Levittown-like development, the cheap uniformly neocolonial houses of Eddy Street had been thrown up on the site of a plowed-over farm and apple orchard. A busy thoroughfare—Landham Road—connected Sudbury to Saxonville, a rather desultory collection of brick mill buildings that had seen better days. But the traffic effectively cut us off from the wider world. Eddy Street denizens seemed to be claimants of an obscure, freshly buried and irrelevant past, isolated like an Amazonian tribe that has lived for hundreds of years next to another but never known of its existence. The blissful backyard lawns, having been bulldozed of trees, blended seamlessly into a singularly blissfully unbroken suburban desert as far as you could see.

Oddly, such an a-historicized landscape also managed to yield more than its share of precious semi-historical artifacts. Over the years I stumbled across oxen yokes, a Conestoga wagon wreck, hulks of old cars in the scant surviving woods behind our house. Incidentally, our yard also contained a geological oddity that seemed part of an even more ancient past: a hundred yards back from our house, where the Eddy Street development had been stopped at the town border, was a natural amphitheater, banked with high steep slopes, and enclosing a small flat patch of land. The grove we called it. Sometimes we boys flung ourselves from the grove’s sloping banks, seeking, one reckons, a token of desire to exist out of bounds.

One day we heard on the radio—there was always a radio in those days—that a prisoner had escaped from a nearby prison and possibly been spotted in our neighborhood. We kids were all told to stay indoors. Hoping to get a glimpse of him—a guy I imagined wearing a striped uniform who’d be sufficiently menacing to make looking worth the risk—I peered out between a gap in the dining room curtains. Maybe I even opened the side door and stepped out of the porch, electricity jolting my nerves. Who knows?

Eventually, I suppose, he must have been apprehended without a shootout or a chase. I didn’t hear anything on the radio anyway, or from my parents, or if I did hear about the moment it didn’t register with enough jolt for me to remember it now. In any case I never got to set eyes on the guy. The narrative was a bust.

Summers passed. We kids (even our names spoke of a certain freebooting exuberance: Chuckie, Dean, Bib, Dickie…) roved the neighborhood unimpeded by phantom escaped prisoners. We made up our own games and dramas with an assumed proprietorship—in ragtag parades, clothed in garb of Korean war veteran fathers, or in paper bags that we drew on to make up our madcap finery. We were knights, soldiers, and rightful claimants to Eddy Street’s obscurer precincts. One summer we formed a regiment to give battle to regiments from nearby houses. We patrolled Eddy Street on our bicycles (my Schwinn Lemon Peeler, modified with a glowing skull figurehead, being the pinnacle of chopper aesthetic), and swung gigantic tree branches at one another until we collapsed, our bodies depleted. Untethered from adult oversight, we were free agents, feral roving bands.

Let’s just say it. There’s something almost invigorating, almost subversive, about homogeneity of enterprise. I don’t mean this in a nativist/ignorance of outside influence way. I mean it, perhaps, in a knowing of the self as an infinitely variable commodity way, and locating that self in a culture that bolsters it, even in the short term. Of course, culture’s malleable, unruly, unreliable. Of course. One’s place in any culture conditional. But, looking back, it seemed for a moment that for all its blandish pleasures my brief Eddy Street tenure had come at a particularly harmonious time and place, and that its effects were longer lasting than I could have ever anticipated.

But what really prompted the writing of this little essay wasn’t directly related to my childhood at all. It’s something that happened in the neighborhood almost forty years before I was born, and was relayed to me decades after I lived there.

On a warm summer evening in the late summer of 1925, a group of local men, and more than a few from nearby towns—possibly two hundred in all, two-fifty—gathered at a farmhouse on the property my family would own some forty years later. In my imagining, there’s a fine mottled sky, fireflies, clouds, an ambient buzz of mosquitoes, Model T’s looking for parking. The cops were out, state as well as local. The owner of the property, a Spanish-American War veteran and farmer, F W (Perley) Libbey, is a figure obscurely infamous, mostly lost in history’s churning. But one can picture him, as I do, middle-aged, lean with hard labor of farming, suspicious of anyone outside his orbit in way that seems perfectly contemporary. On the night of the gathering, he’s rushing about, making sure cars don’t park in the fields, glad-handing guests, chuckling with the cops and locals about the more-than-expected turn-out, and the possibility of trouble.

Libbey was no innocent, no dupe. A few weeks earlier, he’d been arrested for wielding an unregistered gun at a KKK rally in Westwood, Massachusetts. Klan rallies had been held at his farm earlier that summer, threats made to Catholics, Jews, newly arrived eastern European immigrants. He was up to his ears in vindictiveness. On the night of the rally in what was to be my backyard—probably the grove, bound by the slopes I loved to tumble down—men in the vestments of the KKK were waving placards, flags, burning crosses, their chanting the unregenerate gibberish of those assured of their righteousness.

By six o’clock, the Model T’s, Nash coupes, Durant sedans, were lined all up and down Landham Road (the busy road that we kids would one day be forbidden to cross), it was nearly impossible to get through the phalanx. Latecomers were getting out, walking half a mile. They carried an assortment of clubs, shotguns, pistols, American flags, placards, as if readying for patriotic display. Some came wearing overalls, or suits and neckties of the era, stubs of ties slapping over bellies. Many—most—were wearing white robes, hoods pulled off to let the heat out, and in the mellowing light you could see their faces, reddened, their mouths slackly breathing moist unmoving air.

New group members looked around, seeing where they fit in. Greetings were extended— crushing handshakes. How could they help. Indoors, two or three women cooked pies in a coal oven. All these men were going to be hungry. The lull was proving itself to be comfortable. A few protestors, the Irish, the Italians from Saxonville, where flourishing carpet-weaving mills attracted low-wage workers, were hanging around by the asparagus patch, but not like it was in Westwood.

Pop culture between-wars pre-Depression America came on as modern, uptown, flapper- in-the fountain, jazz-mad pastiche, boardwalk beauty contests, T J Eckleburg, Harlem…. But pockets—nay, great swaths—of America lighted their houses with kerosene (the Libbey farmhouse could have been one), got its news from Readers Digest, and workaday life might seem hardly different from life under, say, the administration of Martin Van Buren. Boys had tramped off to war on the Continent in 1917, presumably returning with visions of Parisian footlights as well as the trenches, but there’s endemically stubborn provinciality in American life—a nasty flip side of our myth- aspiring individualism. Did a couple weeks leave in Paris matter when you returned to the homestead and had to start digging ditches, and an Irishman or Armenian had moved in next door? Even during the War, when black soldiers (in segregated regiments) beat back the Germans in the Argonne Forest, provinciality at home never stopped flirting with terrorizing racism. D W Griffith’s bogus epic of a film, Birth of a Nation (1915), idolized the original Klan, and soon after its release a resurgent second-wave Klan expanded the mission with an anti-Catholic, anti-Jew, anti-Italian, anti-pretty-much- everything-not-born-on-the-Mayflower agenda. All over the South, Midwest, Northeast, the new Klan stepped up its intimidation efforts, like a boosterish Kiwanis club with race war on its mind.

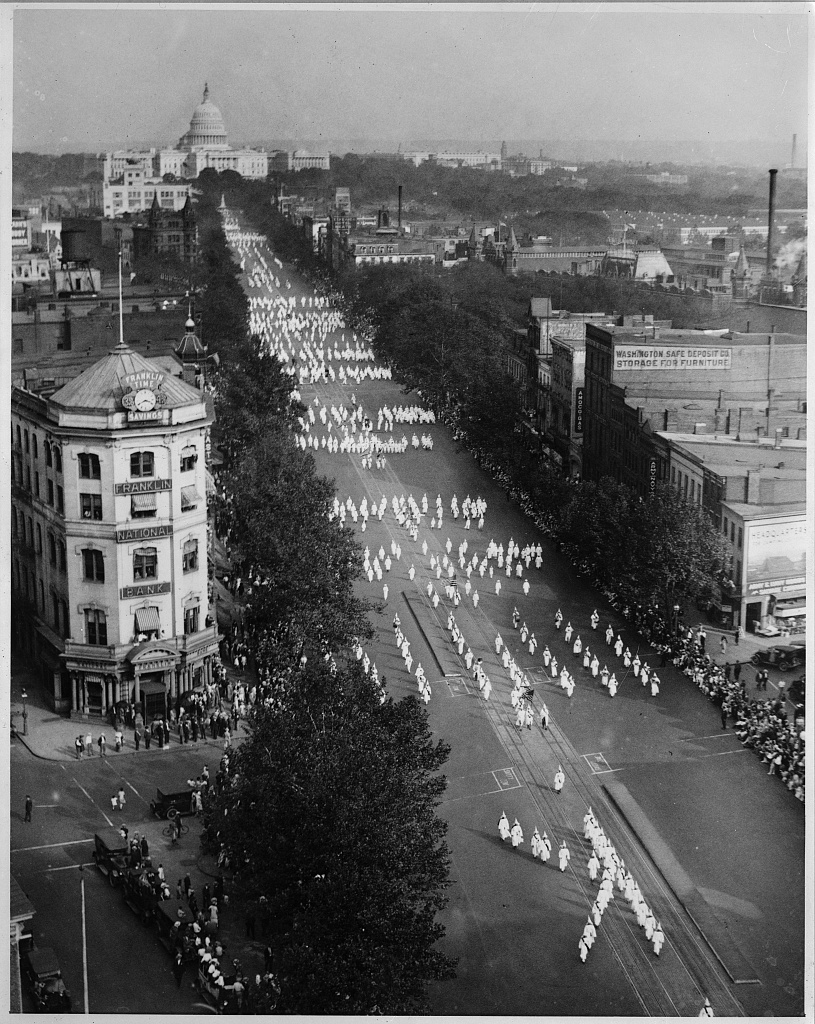

One only has to follow the segregationist folly of Know-Nothingism to Jim Crow to the Immigration Act (1924) to get a pretty clear picture: the Klan was just a silly costumed manifestation. The original Klan had topped out at a hundred thousand or so members, mostly ex- Confederate freelancers trying to fend off Reconstruction and hold onto a slippery white hegemony. But by 1925—the peak of the second Klan’s cultural saturation—the Klan could muster, nationally, some four million members, give or take a few million. In Massachusetts alone there were estimated to be 80,000 hooded costumes ($6.50 each) hanging in the backs of closets of farmers, merchants, ministers, police captains, bankers, undertakers, teamsters, shop clerks.

Nineteen-twenty-five may have been a pretty slow year for lynching—only seventeen African Americans were tortured, hanged, mutilated—but just a few days before the events at Libbey farm, some 40,000 Klansmen paraded through the streets of Washington DC, singing, jabbing the air with their signs, marching in formations of crosses and the letter K, demonstrating the Klan’s power in the very heart of the democratic experiment. And it was in this superheated atmosphere that immigrants, mostly first generation, some Irish, Italians, came ambling over the hill from Saxonville, down dirt-paved Landham Road, confronting the armed and riled-up Klan at the Libbey farm.

It’s impossible to piece together exactly how things started, but maybe not hard to piece together how it accelerated. Feeling an advantage in numbers, protestors pressed on the farmhouse, barn and chicken coop; Klan members, feeling cagy, telephoned for reinforcements and got through to some guys getting off the shoe factory late shift, maybe an accountant or who’d already turned in for the night. In the next hour or so, additional men—twenty, thirty—were coming down Landham Road from the north, beating their way through the protestors. By this time it must have been 11:30, 11:45.

Names were called, let’s say. Papist. Shit-for-brains. Stronzo. Someone bent down to pick up a rock. Someone hurled a piece of an oxen shoe. A Klansman was hit in the shoulder. On the side of the head… a broken nose gushed blood and snot. The cops were doing their best, but they’re they’re human, they’re not trained for this. A furniture store clerk—maybe he’s a kid, twenty-three—waved a rifle out the chicken coop window.

Everyone around him started clamoring, taunting, then you can’t do anything but shoot, can you. Maybe he doesn’t even remember after a while. One of the Irish spun around, crimson pooling in his shirt. It was on his face, blood everywhere. The guy was just standing there, like he forgot something at the store. Now other guys started firing into the crowd, and protestors, trampling over each other to get out of range, were shouting, sobbing, cursing, lobbing back rocks.

Five protestors were left behind, binding their wounds with their fingers, licking blood. William Bradley. Frank Maguire. Edmund Purcell. Thomas Sliney. Hit with buckshot. 22. Also Alonzo Foley. The guy who hadn’t moved. Alonzo crumbled to his knees now, holding his head with a cocky grin, his eyes fluttering. Twitching. A priest, youngish, soft-handed, his hair tight to the scalp, murmured last rites, giving the sign of the cross. After a while the others got taken off in Saxonville taxis, to a doctor presumably sympathetic. Alonzo went in the back of a four door sedan. Now it was probably around one o’clock in the morning. Maybe later. Kids hanging on the edge of Landham, losing interest. Dogs pacing up and down. State Police, motorcycle cops spread out over the asparagus fields, the orchard, and chicken coup, rounding up Klan guys, Sudbury guys— Curley Libby, Robert Atkinson, Ralph Chamberlain, Oliver E. Ames, Harry Rice—some of whose names are on municipal buildings these days. Guys from Waltham, Needham, Newton, Wellesley. The son of the police chief got scooped up. Light was starting up over the trees, ragged, unconvinced. Nash roadsters, Model T’s paused, trying to get through, the drivers squinting through smudged spectacles on their way to work. A couple half-eaten pies were strewn across the farmhouse kitchen floor, the Klan women raking up the mess with forks and dustpan. Alonzo was supposed to die in the middle of Landham Road, buckshot to his temple. But the fact is he didn’t. He lived until well after my family and I moved away. In 1979, at age 87, Alonzo died. I was on to other things by then, pursuing my own academic and literary aspirations, leaving Eddy Street far behind, I hoped.

Nineteen-twenty-five had proved to be the high water mark for this version of the Klan. The march on DC was the largest assembly it would ever muster. By the 30s, wracked by scandals, internal corruption, and external resistance to its vision of a racially, morally unanimous America, the Klan shrank to a few thousand members, persisting only in isolated chapters throughout the country. The respectable attorneys, bakers, mechanics, farmers, returned to harboring their grievances in less civically boosterish ways, or modified them in accommodation of a world that wouldn’t cooperate with their mania for purity. By the time my parents purchased their Eddy Street plot, I could live in relative obliviousness of the events of forty years earlier, free to cruise on the Lemon Peeler over land where old Libbey had meant to make his stand. Only, like some virulent strain of bacteria, the Klan did reconstitute itself in the civil rights crisis of the late sixties, at the time Libbey himself had gone to his grave (1965). A virtual protectorate of the intrenched Southern political power structure, it renewed its commitment to subjugation through night-riding vigilantism, murder, terrorism.

America tilts to the affirming word, the frisson of possibility, a kid riding a bike. But it’s reminding you. Always.