Compulsory patriotism:

The National Anthem as sports ritual

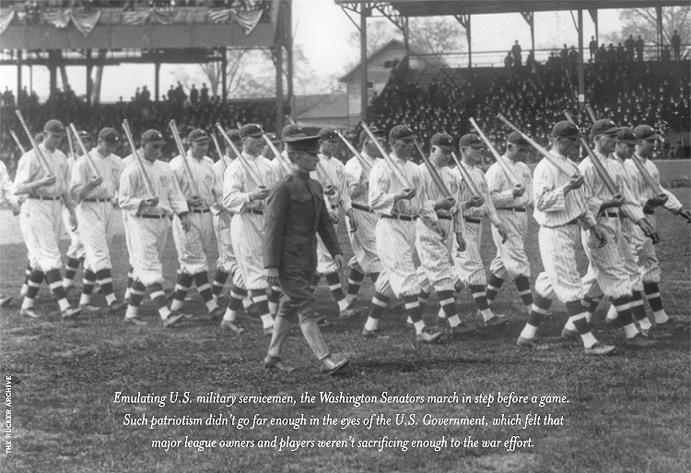

In the summer of 1918, baseball’s relatively early days, before the game became so self- consciously uppity about being a national pastime and all, you’d see doughboys about to be shipped off to Ypres and the Ardennes (including lots of young men who a few weeks before had been wearing the uniforms of ball players) parading in formation onto Shibe Field, the Polo Grounds, Ebbets etc. Players in team uniforms shouldering bats like trench guns. And martial displays like this were often accompanied by brass bands playing popular songs of the day (Ostrich Walk, Over There, It’s a Long Way to Tipperary), jaunty performances that inculcated fans with a sense of catchy good cheer. On occasion a band’s repertoire might include America the Beautiful or My Country Tis of Thee, stirring a not-so-latent sing-along patriotism in the grandstands. But in the first game of the World Series that year, during the seventh inning stretch, a band struck up an old drinking and whoring tune, now reconfigured by Francis Scott Key via John Phillips Sousa as the Star Spangled Banner. The stretch had been around in one form or another for a couple decades, its origins lost in tobacco-stained mythos of Wee Willie Keeler and Charlie Buffington days, but the Anthem had been played only sporadically before this. In 1918 it hit the zeitgeist in the gut. The Spanish flu pandemic was killing hundreds of thousands, the Great War churning on with no end in sight. Anarchist bombs were going off in American streets. Emotions were pitched. Some Red Sox and Cubs players saluted the flag or, hands over hearts, lustily sang along with the band. A few spectators wept openly. Also, don’t forget the Anthem hadn’t yet been encumbered and enhanced by a million emotionally overcharged renditions at every county fair and Super Bowl, but its yearning for familial reunion seemed to align with growing national communalism, conjuring friends, lovers, husbands, brothers half a world away. By 1919, the Star Spangled Banner was off and running. It was already the de facto official song of baseball, a sacred yin to the secular yang of Take Me Out to the Ballgame.

Anyone who’s ever been to a ballgame knows there’s something lovely, sublime even, in massed decidedly amateur voices belting out the Anthem into a ballpark’s vast green spaces. But such displays also scold. As with lots of facets of American life, patriotism in early baseball ordinated rather unhappily with congregational piety. Stadiums full of people singing together tended to veto the dissent of those who weren’t so ready to get with the program, or weren’t even invited to the program in the first place. 1918—year of the Dillingham-Hardwick Act—rooted out communists, labor organizers, anarchists, and shipped them back to from whence they came (eastern Europe, presumably). A few years earlier the movie Birth of a Nation had rebooted the Klan franchise, generating waves of anti-Catholic, anti-Black, anti-Jewish sentiment across the country. Baseball’s uptake of patriotic displays into the game’s custom and lore assumed political, racial, behavioral conformity. It assumed some valence of martial righteousness along with the shared sentiment.

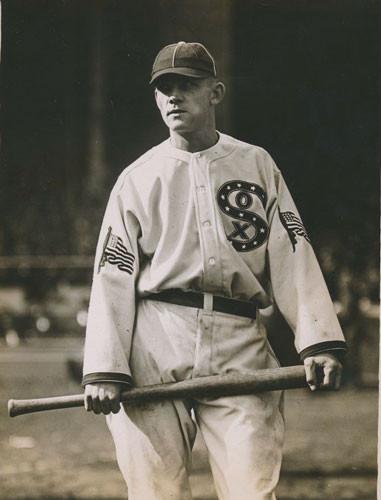

When Shoeless Joe Jackson, uneducated and arguably the preeminent pure hitter of the era, tried to get around the draft by registering as an “essential worker” at a shipbuilding yard, fans and the press went after him, labeling him a draft dodger, a traitor and, implicitly, unpatriotic, a pinko. Imagine—the gall of not wanting to die in a haze of chlorine gas, or machine gunned in snarl of barbed wire in a war of global madness.

One genuinely wonders about the nexus of sports and national boosterism in the first place. Do games, inherently, constitute a patriotic exercise any more than doing the dishes? Maybe they do. Games as performance pieces, heeding national interests, played over and over again as variations on the martial theme? Maybe— OK— But from the earliest days of professional sports, the moral imperatives were hard to separate from the financial, and from corporate manipulation of sentiment. Not only were customers— good, paying customers—sneaking away from the office to be treated to the spectacle of young men batting and catching balls, but with a little moral uplift might these customers come a lot more often? Marching bands, the Anthem, soldiers, recruiting booths, elevated the ballpark experience to that of sacred national ritual. Owners got it—the way owners understand the bobblehead.

Next year, with the Great War having ground to an end, and the country in a mood for returning to peacetime routines—and Shoeless Joe back on the White Sox—the Star Spangle Banner was routinely played in the parks, a de facto anthem for American unity (or some version of unity: baseball grandstands in 1918 were places for men in bowlers and boaters, factory workers, office workers, gamblers, swells, family men—white men).

What was being sold, subliminally, was a storied tradition of patriotism as martial covenant. Patriotism and war may not be entirely synonymous in this country, it’s true, but let’s face it—our origins are in the violent overthrow of paternalistic shackles, the righteous and viscerally horrific upheaval that was the American Revolution. Wave a flag—you’re acknowledging the collective memory of the Revolution. And possibly elevating the pastoral version of the story to the status of myth. Hold hand over hearts, have a beer, root for our home team in the August sun…. What’s the net effect?

The Anthem’s lyrics remind us:

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming… And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave….

Chronicling an obscure battle in an obscure war, the words call us to acclaim all that gleaming and streaming. But our vantage—Francis Scott Key was eight miles from Fort McHenry—is pretty limited. The blood and mire, gruesomely shattered bodies, aren’t visible, even by the rocket’s red glare.

Building a nation, as it happens, is rife with tar-and-feathering, finger wagging, idealistic, philosophical, intellectual thrashing about, battle scars, young men dumped in shallow graves, stubbed-out butts of utopian dreams. But from the perspective of a pastorally green ballfield on summer’s day, the grimmer aspects appear rather hazy. Even in the grandstand’s more urbanized welter of cigar smoke and spilled beer and body odor, you accept a folksy Spirit of 76 version of patriotic gumption.

By the time the US entered the Second World War, baseball had established itself as the national pastime without peer in professional sport. The NFL, in a protracted fledgling phase, lagged far behind college football in popularity. The six team pro hockey league was small potatoes, and Canadian to boot; makeshift basketball leagues and barnstorming teams came and went in middling industrial cities without leaving a trace. As the quasi- official game, in part by default, baseball lived with all the symbolic burdens that entailed, and was tacitly entitled to its share of national prerogatives. Presidents from Taft to FDR had thrown out the first pitch of the season. In early 42, FDR wrote a letter to the magisterially named Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, explaining “I honesty feel it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.… These players are a definite recreational asset to… their fellow citizens. And that in my judgment is thoroughly worthwhile.” A fine line that eventually introduced young teens, one-armed outfielders and wooden-legged pitchers to the majors to keep the game going (though integration as a means of filling the ranks was barely considered). The day after Pearl Harbor, Bob Feller, the Cleveland Indians pitcher who’d dominated the league as a seventeen year old in 1936, famously drove down to his local Navy recruitment office and hitched up. Players weren’t exempt from selective service, Roosevelt told Landis, but lots of high-rent players like Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Stan Musial, though officially enrolled, played out the 42 season. Williams eventually became an ace flier. DiMaggio, Musial and others, protected by their status in a way that lesser gods were not, spent their time sunning in California, Hawaii, playing exhibition games, demigods in palmy exile. At home, between games of a doubleheader, Babe Ruth—creaky and bloated from hotdogs, beer and retirement, slow to get around on the nickel curve—pulled on an old number 3 uniform and, taking swings against the Big Train (Senators totem Walter Johnson), raised money for Army-Navy relief. As newsprint sloshed with rolls of the dead, the Anthem was played at every home game, as salutary as it was compulsory.

Putting aside the slightly inconvenient reality that the alliance that beat the Nazis included a country ruled by one of the greatest mass murderers in the history of the modern world, you might agree that the eventual allied victory evoked the clearest moral triumph of good over evil in the history of the modern world. And the country had every right to feel upright. If, incidentally, the war also incited faith in the hegemony of industrial capitalism, of tanks and Jeeps and battleships and American bomb building know-how—the smug chauvinism of moral rectitude that comes from discovering one’s nation wielding the closest thing to absolute power a country has ever known—that was the price of admission. Professional sports wasn’t slow to take up the cry either. The strain of intolerance of the Great War was blooming into post WWII boosterism. Tail Gunner Joe rising. By 1942, most baseball teams played the Anthem before the game.

Upping the ante, the NFL mandated in 1945 it be played for every team for every game.

“The playing of the national anthem should be as much a part of every game as the kickoff,” wrote Commissioner Elmer Layden.

Nowadays at pro football games, a PA announcer with a voice like a third world

generalissimo’s decrees the crowd remove hats, place hands over hearts, salute, genuflect, sit. Absent exercising any deeply felt patriotic impulse to read the collected works of P T Barnum, you reflexively follow instructions, heedless of their high kitsch. The veterans of Iran or Afghanistan in clean uniforms and gleaming medals come onto a field and wave to the crowd, cameras zooming in on their faces, symbols of they know not what. Do they ever wonder if they are being used, trotted out, wadded up, tossed away? Are they disoriented, dumfounded by schisms in their experience? The thing they’re supposed to be celebrated for devalued by the very celebration? For the fan, try sitting in your seat, drinking your beer, thinking of Antietam, Daniel Shays, Jackie Robinson, you look like a jerk, an ingrate, indifferent to the blessings of a country that’s mostly tried to live up to its high ideals. But could it be the opposite? That one can care deeply about one’s country, and shun the hireling ordering you to put your hand on your heart (a tradition, by the way, stared in 42, along with recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in school).

Colin Kaepernick takes a knee. Colin Kaepernick does not salute. Colin Kaepernick has hair like terrestrial tumult. This is history quivering with meaning, giving off inventories of vibrations. You don’t even have to agree with what Colin Kaepernick’s saying to grasp it. It’s perhaps the most genuinely patriotic answer to the Anthem’s real plea. Such allegiances are liberated from common pietism: protesting America is the precisest expression of Americanism. Not the faux of entitlement, narcissistic graspingness, rampant Jeffersonian or Tea Party or Ayn Rand nullification. It’s a protest of mystic, epic proportions. Ask Jackie Robinson—Brooklyn second baseman, Branch Rickey- and self- nominated avatar of race equality, dutifully read about by every single schoolkid in the country, stealing home in game one of the 55 World Series—who, in his biography claimed the right and rite of dissent: “As I write this 20 years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem,” he said. “I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.” It’s a paradox at the center of everyday American life, the hue and cry of the Concord transcendentalists and liberal Constitutionalists, John Brown, Colin Kaepernick, the tricorn-hatted yeoman and doughboys charging through Belleau Wood, Jackie Robinson, rising from patriot graves, rumbling beneath the grandstand sincerity of the Anthem singers.