Part Four:

The Beguilement of Righteousness

HISTORY OF VIOLENCE IN AMERICA

In America violence was an abstraction coming out of the country’s cracked soul. Maybe from the moment Americans started fetishizing a single piece of paper as ipso facto destiny, violence was guaranteed social legitimacy, and vouchsafed in the national drama. Pugilistic rhetoric as philosophical manqué. It produced an erotic jolt, orgasmic catharsis.

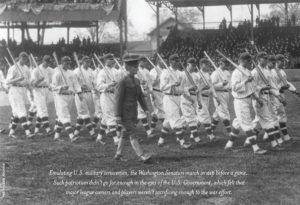

America, here’s the thumbnail version: Puritan hostility to joy, Indian wars, convulsive Revolutionary dramas, the overthrowing of patriarchal yokes, the internecine bloodbath of the Civil War, tableaus that have been drummed into every schoolchild’s brain from the age of six, the means flipped as end. Feasting on tv shows, novels, the movies, nightly news, Youtube—the brawling, stakeclaiming, fistfighting, streetfighting, bowie-knifing, gunslinging, chest-thumping, bare hands boxing…. Americans couldn’t get enough of the storyline. Assassinations, mob hits, Jesse James, Jim Jones, Ma Barker— Perennially righteous wars overseas— On Memorial Day ever-aging veterans of ever-distant wars parade down Main Streets, their old rifles and rakish hats assembled as a charade of their deeds, codifying their cultural eminence (once when they were young men they resolved by force of will and arms to liberate the world of its ills). Domestically, an arms race of citizens equipping themselves against fellow citizens in anticipation of some orgiastic shootout, the righteous gun-toter having lived out the national fever-dream, the bad guy going down in a pool of sublime blood.

As it happened, the first recorded murder in Europeanized America occurred in the settlement of Plymouth Plantation. In September of 1630, one John Billington was tried for the murder of one John Newcomen, and was hanged in October, almost precisely a decade after the Mayflower landing. We speculate, but let’s speculate: Billington, matchlock in hand, having gotten into the cider or beer, was roaming the woods around his house one day and came across Newcomen (or Newcomer, or Newman, his surname likely a marker of his status, not his family), and shot a warning shot that inadvertently killed him. Without precedent in the New World, one had to conceive of such a thing as waving and shooting at another person, didn’t one? One had to aim the loaded matchlock. One had to pull a lever to lower a smoldering match into the flash pan and ignite the priming powder. One had to deliberate before being the first European to commit murder in this New World. One, in other words, had to break through all built-up implicit and explicit cultural injunctions against such a thing. One had to conceive.

But violence, of course, was no more invented by John Billington in America than apple pie. Nor were pilgrims and joint-stock company holders of the seventeenth century the first to subject one another to bloody torment in the name of enforcement of religious or civic order, any more than they were first to resort to violence to keep trespassers out of their cornfields. The Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation periods, for example, were some of the bleakest and bloodiest in human history—some hundred and twenty million killed over the course of roughly three centuries. The violence imported into the New World came from good stock.

And though the Puritans, Quakers, Anglicans, Pequots, Wampanoags and Narragansetts who were trying to sort themselves into camps hard by the shores of the Atlantic did manage to hold off slaughtering each other a while, the King Phillips War (1675–1678) left more than 3000 Indians and 1000 settlers dead. Little more than a decade later, following the Salem Witch Trials (1692-1693), the Reverend Cotton Mather, writing about the Second Indian War (1688-1697), envisaged the everyday monotony of the killing fields: “On Jun. 24. one Thomas Cole, of Wells, and his wife, were Slain by the Indians, returning home with two of his Neighbours, and their Wives, all three Sisters, from a Visit, of their Friends at York: And, on Jun. 26. at several places within the Confines of Portsmouth, Several Persons, Twelve or Fourteen, were Massacred, (with some Houses Burnt,) and Four Taken….” Settlers and Indians alike must have taken violence as just atmospherics. One can scarcely wrap one’s head around the abruptness with which savagery could be visited upon farmers hoeing their maize and sweet potatoes, the mental ramifications of living through massacres that took scarcely longer than time it took to draw water from the well. Was it twelve or fourteen? Hard to keep track.

We might say, yes, yes, violence pervaded the pre-Revolutionary America landscape, and continued through the Revolution—a carnage some historians claim was even more wrenching than the Civil War—but weren’t we also talking about the Reformation, European violence, the heads of executed priests rammed on pikes aside highways as far as you could see? Is the history of violence in America any different from history of violence elsewhere—? What’s so special about American violence? Even dueling, the gentlemanly sport of killing a socially worthy opponent over sneezing in the wrong direction, was a European import, and the classic gunfight of the Old West (ninety-nine percent fiction anyway) was no more than an updated enactment of ancient code duello protocols, replacing French pistols with six-guns, and handkerchiefs and white gloves with bandanas and white hats.

But violence in America has always had a certain boasting elan that gives the country its special brainless swagger. Another salient point: America, for all its parades and infatuated biographies of the Great White Men, forgets its history as quickly as it can be manufactured. Who can tell you the names of Revolutionary generals besides George Washington? No one remembers the Maine.

The point is (let’s be as clear as possible), in America violence saturates everything. It obscures past violence with ever-new obliterating violence, it reconstitutes violence in the form of tv shows, billboards, political assassinations, rallies, school shootings, the masturbatory contests of gun fetishists, scribblings on mens’ room walls, essays on violence, and feeds them back to us to satiate our appetites. Civil War hobbyists in authentic looking garb, acting out the barbarity of war, stumble and fall from make-believe wounds then return to their cars in a parking lot at Gettysburg for a brewski (Treblinka reenactors anyone?). A guy at Starbucks orders a cappuccino, AK47 on his shoulder, like he thinks he’s a Revolutionary Minuteman or something. Al Capone was a psychopath who would as soon have slit your throat as let you borrow a dollar without interest. Restaurants get named for him. Joseph Smith, marshaling his Nauvoo Legion, would have ordered open fire on anyone who stood in the way of his vision of new Zion. Now a saint.

You get where this is going. We accept it as our due. It saturates our collected being. When, in 1901, young Leon Czolgosz took it upon himself to kill President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, it seemed he might have been following a tradition of European-oriented political assassinations. On the continent, after all, assassins had tried to take out half the major European heads of state of the previous century. Franz Joseph, Kaisers Wilhelm I, Friedrich III and Wilhelm II, Tsars Alexander II, Alexander III and Nicholas II, Victor Emmanuel II, Umberto I and Victor Emmanuel III…. all came under attack. And in early twentieth century America, the tendencies of the anarchist movement—with emigres like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman preaching in Union Square, reading material like L’Indicateur anarchiste or Free Society sold at every corner bookstore—made the McKinley assassination a plausibly European endeavor. But Czolgosz, a Michigan-born trade unionist and semi-professional anarchist (in an era when anarchist was a clearly understood métier), had chased McKinley halfway across Ohio, Michigan and New York, a cross-country odyssey akin to Huck Finn’s or Humbert Humbert’s. Approaching the president in the receiving line with ready-made American style intentionality and intimacy, he took aim. No dynamite under the carriage for him. No emperors and consorts blown to bits, epaulettes and silk knickers and brass buttons strewn across the cobbles. Czolgosz’s aesthetic was purely in line with that of other American assassins: a lone man turned gunman, identities merged into singular actionable noun, meting justice up close, the homicide inherent in the democratic contract. The gun itself, a homey American-made 32-caliber Iver Johnson Safety Automatic, had been purchased over the counter a few days before. And then there was McKinley’s own lack-of-ceremony meet-the-people glad-handing style that added to the moment’s characteristically democratic flavor. In 1901, two of the last twenty-five presidents had been assassinated, and now McKinley, standing in the Exposition’s Temple of Music, beaming at his constituents, would notice the safety pistol thrust forward under the shroud. He would make the third.

Our mental view of the country takes in, as fable and fact, vast arsenals of switchblades, homemade bombs, garrotes, nooses, brass knuckles, shanks, matchlocks, AK47s, handguns, and we take for granted, also as fable and fact, the national saga of assassinations, public lynchings, garrotings, movie theater rampages, drive-by shootings, domestic beatings, street riots, the casual barbarity of highway rage, the institutionalized rhetoric of indifferent cruelty, barbershop mob hits, bombs in mailboxes. Maybe no one knows John Billington, maybe no one knows Leon Czolgosz or cares a whit about him, but the violence that resonated with people like John Billington or John Dillinger or Leon Czolgosz or Sirhan Sirhan or John Wilkes Booth has always resonated in the collective circuitry: violence as societal suicide, violence as tautological response to the violence that came before, violence as a jumpstart, violence as the logical expression of the democratic experiment and violence as spilling over of righteousness, violence as failure of imagination, violence as an imaginative leap.

TO BE OR NOT TO BE

He’d forgotten about yesterday already, he wakes up to beige walls, a framed red-saturated desert landscape, light coming in around the curtains, the Motel 6. He’s not sure exactly where he is, how he got here. His wallet, wrappers, guitar picks, loose change, the detritus of bomb makings (bbs, batteries, wires) are strewn across the covers. The pillow’s on the floor, his back a dull ache creeping to the back of his neck and into his sinuses. He stretches, but still— In his wallet are exactly six twenties, a five, ten tens, about a thousand ones. Enough to last how long? A week, maybe less. Even at $35 a night you can’t keep staying every night in motels, he instructs himself, sternly calculating the cost of gas and the distance back to Pine Island or Menomonie. Seven hundred miles from home, give or take. The chocolate shake from last night is warm, its sweetness oversaturated, the chemical balance having tipped in the course of the night.

The room, inhumanly stifling, takes him deeper into himself—mental detours and refractions, thoughts ramifying into the ineffability of hollowed-out spaces. Throwing the covers back he gets up and paces in his underwear. A suddenly flabby belly that can’t be sucked in greets him in the mirror on the door. The picture on the wall provokes a memory of uninterrupted outdoor vistas, but he opens the door into an enclosed space of mauve-carpeted hallway that stinks of antiseptic. Doors are closed, Do Not Disturb signs hang from door handles like wishful missives to a disagreeable world. He pulls shut his door, pulls the curtains aside.

Outside, in a mild drizzle, the parking lot’s filled with cars dutifully sticking between the lines, rain puddling on their generically gray and white painted bodies. The lodgers, even in their diasporic travels, are seeking some sense of collective belonging, he thinks. He too is now as far away from everything he’s ever known as he’s been in his life. And familiar things (roadsigns, names of chain stores, an old man’s grinning whiskery scowl…) are off, slightly askew, as if the world’s tilted but not much—half a degree—on its axis…. He recounts his money, this time comes up with twenty dollars more. A good sign, he thinks. Twenty dollars. He doesn’t count again, lest the new twenty be lost again. It’s been months since he talked to Skyler, but he sniffs the room’s sharp funk for some trace of her. Hoping for what? A remnant of her enchanted presence, her sad giddy keening kisses? But she’s gone. Gone. Definitively. Never coming back. It wasn’t her fault, of course. He had ceased to be enchanted; no, that’s not quite right, he had no longer been capable of enchantment. Only now her face, her lovely pirate face, appears vaguely before him, offering forgiveness. He splashes his face in the bathroom sink. And splashes again. Listens. He remembers her clarinet playing, which had charmed the varsity team as beguilingly as a snake charmer’s instrument. If she hadn’t agreed so easily they were over, might they still be together? Might he not be where he is? He loved her, he realizes. Loves. After kissing her her on porch the last time, he’d driven away in haste, then quickly U-turned by Custer Park and returned to the house, parking in the street, not the driveway. He left the motor running, a low reassuring gurgle to go along with the chorus of insects that added to the night’s mystique. Over the tv’s squawk he could hear her parents’ bickering, murmurous and long-practiced, the long slow-burning feud of their marriage played out in accompaniment by dramas created on Hollywood lots. Skylar the cast-off product of it. The porch light was still on, as if she were waiting for him, the yellow bulb signaling the besotted insect congregants. He approached, passing a rusting lawn mower that had been left to its own devices months ago, and sat down in the spring chair. There was still a trace of warmth from her from half an hour ago, some measure of her in the momentary stillness. Then tv voices came back, drowning out her parents’ resurgent querulousness. Psychiatrists are sissies, he heard her father say. What did Skyler mean when she’d said to him that night that he was a professional outcast? He couldn’t be sure he heard her right, the way her voice hung in the air a fraction of a second after she’d finished speaking, like an echo. He could show her he wasn’t. Was it too late to knock? Or would it just frighten them? He cracked one of the Schells her father kept in a cooler and settled in. One, then another. He set the empties in an orderly row next to the chair, and relaxed, letting the cool breeze slip over him. Next morning he woke to her father nudging his shoulder. Luke stared into old man Cassidy’s face, crevices running across his forehead, his teeth in a collected ruin, the expression in his squinting blue eyes plaintive, cruel, understanding. Luke bolted barefoot across the yard. His head pounded in the perfection of a sticky-hot new morning. The car had run out of gas in the night.

It’s a relief to see the golden arches across the street. In the motel lobby, starting at six, there’s free continental breakfast: apple juice, Fruit Loops, bagel and creme cheese out of plastic tubs. But his flabby belly is forgotten quickly, and his budget. The thought of hash browns and Bacon, Egg & Cheese McGriddle, fried sausage processed into perfection, makes his stomach grumble. At a table in the McDonald’s he studies the map. Today he’ll be driving to Oklahoma, Texas, places he’d never had reason to think of going before. He has enough raw material for ten devices, maybe another few if he goes light on the bb’s. He takes a pen from his backpack, and clears away the hash browns and McGriddle. Dear Cameron, he writes….

If he were to die today, would anyone be able to discern the design he was creating across the entire country? Would the Manifesto be received if no one could read in the monumental Smiley Face his attempt to let people know that in living to avoid suffering you actually caused so much suffering? The Smiley Face was dead serious. They needed to see that. Its shambolic grin was what lived in the deepest recesses of his being, this conspicuously upbeat way of being in the world. His Apathy songs, however imperfectly, had expressed hope, a belief that life extends beyond our preoccupation with the present and into realms of paradise. I’m here to help you, to expose you, to inform you, the Manifesto said. Knowledge was the way toward enlightenment. Luke had never been one to hurt people, he’d never deliberately hurt any living creature for no reason. As a young boy fishing with Cameron, he remembered, his hands trembled as he extracted a barbed hook from the mouth of a muskie, his own breathing slowing sympathetically as the fish’s gills labored and trembled in the alien atmosphere, its eyes going black with its slow realization of its demise. When his mother threatened to step on ants or spiders in the house, he’d carefully sweep them into a cup and find a place outside for them. When he heard the news of himself on the radio, he was relieved the only damage was to a postman’s hand, an old woman’s eardrum. He could have made the devices more powerful. They could have left a crater in the ground the size of a boulder. He was careful, methodical. He was deliberate in planning and execution.

He wrote to Cameron, and to the Stoutania for two reasons. The first was that the radio hadn’t mentioned the Manifesto. Someone was blowing up mailboxes in Illinois and Iowa, the newscaster said. A crazed maniac. A psychopath. The Manifesto was the reason. They had to know! The second was Cameron needed to know about the plan. He was not a psychopath. He wasn’t someone who was dangerous. He didn’t have all answers, but he could expose people to the core of existence. Just imagine the possibilities we all have as eternal beings, he had written to Cameron. You might have heard something about someone who was a terrible person, who was doing terrible things, he had written, but I am involved in a journey of salvation.

Amarillo, Texas. From I-40 you can see the ranch not far off, the line of cars angled nose smack down in the desert as if they’d all come crashing down like remains of a broken-up star. E Z L drives by, does a U-turn in the middle of I-40, and drives by again, another U-turn, then pulls into the breakdown lane doing fifteen miles an hour. Already there are about a hundred tourists swarming around the cars like pagan idolaters; he walks out into the field, tapping clods of wet dirt from his shoes. There’s a group of young what he assumes are Germans—to judge by their overthought clothes—approximately the age when it starts to be a struggle to pass for college students, they’re shoving and joking with each other in universally identifiable flirtation rituals. A few stragglers are prying little pieces of souvenir chrome and dried-up rubber from the unresistant cars. He hangs back, watching. Luke pities the Cadillacs. The indignity of their end here in this muddy field makes you consider the original owners driving home from local dealerships, basking in the smell of mohair, leather upholstery and horseflesh glue, windows down, waving at friends and neighbors from a brand new Cadillac. The Detroit industry that created such gleaming behemoths of automotive art was long gone, but the owners, in their scrubbed suburbs, hemmed in by manicured lawns, had gazed out at their cars at the ends of driveways as if they’d never be able to consider a moment past this singular instance of bliss, let alone this— Cans of spray paint are everywhere, generous piles of them. He selects a Krylon purple, an orange and yellow. Lass uns Steak essen, says one of the Germans, a voluptuous brunette with braids over her shoulders, who does a quick leap over a heap of metal scraps and kisses one of the boys on the cheek. Sheepishly, Luke approaches one of the cars, runs his fingers over the fenders. The car predates the heyday of fins. Before America became besotted with chrome and outerspace. He rattles the cans and tags the car: E Z L. Standing back, he evaluates the results with the eye of an artist. The letters, the E and Z, are rendered in geometrically perfect sans-serif, but the L is bent over as if unable to support itself, in tacit admission of fatigue, phallic crisis. Overall, the letters blend into other splashy day-glow yellow, pink, red, tags, declarations of love, pictographs, dates that once stood out from every other date in the life of whoever scribbled them here. Next to his name he sprays a Smiley Face. Almost two feet in diameter. Perfect. The mouth a rueful grin. The yellow is several shades off, but not enough to distract. The Germans have moved onto a car that sports what must have been the peak of Cadillac’s fin infatuation, ogling it in collective unabashed European giddiness. The brunette is on the ground, simulating a snow angel. Look at this fucking bumper, one of them is saying. Fucking great. Fucking great. The sun is stretched to its fullest extent, catching scabby layers of rust that cover seemingly every available unpainted surface. Do they have to replace the cars every once in a while? E Z wonders. How long can anything stand it out here under Texas skies before it breaks down into constituent chemicals, its elemental remains staining the dirt? Turning his back on the Germans, he heads back to the Accord, god, he’s relieved to be driving again, Hüsker Dü’s Land Speed Record in the CD player. He’s whooping war-whoops out the window, taking the first exit he comes to, past a Hardees and a sundries store advertising its eccentric wares (scratch tickets, women’s clothing, discount cartons of cigarettes, Nehis). He turns into the first a street named OK Street and gets out without looking to see if anyone’s watching. The mailbox’s unelaborated smugness irritates him, but he opens it without fuss. But he’s out of nine volt batteries. Jesus, now he remembers. He could go back to the sundries store, but it’s too late for that, he slides the device into the mailbox along with the Manifesto. There’s a scant parcel of bills inside but he doesn’t bother to go through them, as he usually does. He waits in the Accord, All Tensed Up on full blast, catbirds chasing down a lone hawk over a stand of cottonwoods. He taps his fingers on the steering wheel, waiting for someone to come out the front door, down the driveway. Maybe the person would have heard news about the Smiley Face bomber, and will at the last moment realize. But nothing will happen. Nothing will go off. No explosion will cause anyone’s temporary deafness. No bb’s will tear through the mailbox. No one will die bloodied at the end of a driveway. The person will take the Manifesto out of the envelope and read it with growing understanding of its dire warnings. The person will understand.

The map on the passenger’s seat shows the smile half finished, like an astrological constellation that for the life of him he could never figure out. His last stop before Amarillo had been Salida, Colorado. The corner of the smile. After an hour his stomach starts to grumble. He hasn’t eaten a thing since early this morning.

He’s way off course, like some migrating crane blown by a westward wind. He could have kept going, driving clear through to Louisiana, Alabama, Tennessee, West Virginia, stark windblown towns, stark strip malls next to old train stations, the crumbling yellow houses with ever-expectant mailboxes at the ends of driveways. It would have been easy. It would have been a masterpiece of monumental art.

By now Cameron would have alerted the authorities, probably given them the Accord’s description, the license plate number. Someone from the Stoutania would have called too. His eyes catch the eyes of passengers in passing cars: girls, dogs, guys his own age. Everyone goes ninety on the interstates, no one cares, he’s pressing through Nevada, outside Reno, parched gray vistas like old carcasses of run-over animals, and now there’s a flash of a blue light behind him, a chirp of a siren. He doesn’t look. He blinks at the white lines. He’s listening to Molly’s Lips, the sound pressure building in his head, he’s as goddamn alive as anyone who’s ever been alive.