A brief history of being young & adrift in 80s New York.

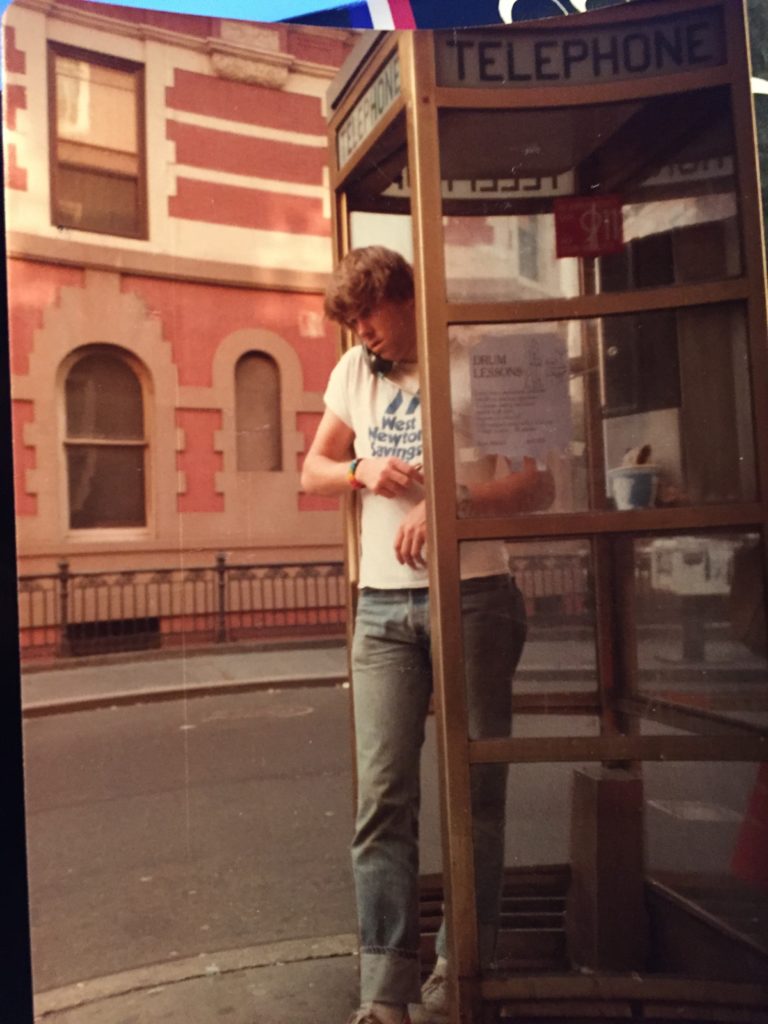

In my young twenties I moved to Brooklyn. At the time moving to Brooklyn was a ritual experience for many young people, like moving to Paris between the world wars must have been, I suppose, or Los Angeles would be for certain cultural adventurers in the 2010s. It was the 80s, before New York became a fairytale mecca, and along with discovering yourself you could also discover multi-chambered LIRR stations with long- shuttered coffee and flower shops, shoe-shine stations, or you could take the train into Times Square and experience the smug seediness of the genuine article, and claim to be living an outré, bohemian life. You could, in other words, still live in relative comfort for not too much money, provided your requirements for comfort entailed no more than an occasional slice of pizza or a few beers on the weekend.

My roommate and I lived quite shabbily in a one-bedroom off DeKalb with a backyard garden we neglected, and a heater that inexplicably turned off on weekends, as if anticipating that we were going to be away in Vermont or the Hamptons, which of course we never were. On all sides, our neighborhood was hemmed in by other neighborhoods where drug deals went down and people were occasionally murdered in rank, dispirited walk-ups. But our street and two or three that ran parallel to ours were shaded with ancient oaks and London Plain trees, there was a park nearby where we would play tennis, and I would run, doing endless loops on a hard-packed path. It had once been solidly middle class but was between prosperous periods now.

Next to our apartment building was a grand abandoned hotel with a marble staircase more or less intact. Sometimes my roommate and I scaled the rusted-out fire escape between the buildings to the fourth story to get inside. You had to stretch your body its full extent and jerk through an open window, a foolhardy move that could have resulted in catastrophe. But once in, you had free rein. Everywhere was debris, horsehair plaster, broken glass, wet slabs of cardboard, wreckage we pawed through in search of some kind of glittering souvenirs. I don’t recall ever discovering anything of value or interest but it was just as well; material evidence of our adventures was superfluous. Phantoms always exerted the most powerful psychic force on me. I’d come to Brooklyn to commune with the likes of Hart Crane and Walt Whitman, who I imagined hovering among the wharfs and printing rooms and ale houses. I wanted to merge with intangible presences, impressing centuries’ of layered ghosts into the crannies of the novel I was writing.

To make ends meet, my roommate got a job with a company that collated dossiers on big businesses. Pretty soon he was making a halfway decent salary. For my part, I was barely keeping alive, financially speaking. I had a couple jobs, one teaching English part-time at a yeshiva, another as a ticket taker at a Manhattan cinema that no longer exists. I often borrowed money from him to cover the rent, and paid him back a few weeks later. A cycle as futile as it was routine. I was forever in small debt to him; and he was forever being outwardly tolerant of the situation. His bed was in the apartment’s only bedroom, mine was in the living room, an arrangement that didn’t seem to cause as much debate or grief as one had a right to expect. We’d been friends in college, and were used to each other, no doubt, and instinctively knew to defer to each other’s claim to the kitchen or the demoralized blue couch he’d brought to the apartment—a luxury, if you could call it that, that made me feel so grown up. Until that time, I hadn’t been acquainted with anyone my age who owned living room furniture.

My roommate was an actor, often away on auditions or seeing plays. Most every free minute I wrote. My novel, about a Confederate soldier, Thomas Leroix, who’d ended up in Kansas after the war, trying to make peace with his memories, was progressing at a steady pace. I’d traveled a fair bit in the South, enough, so I assumed, to unflinchingly assimilate the magnolia-scented horrors of its past into the pages of the book.

Nowadays manuscripts, I assume, are released into existence as if summoned from a hushed electronic ether (in fact I’m writing this on a laptop), no more tactile than a passing thought, but then I typed on an electric typewriter. And the once-ubiquitous sound of typewriters—the commiserative hum of electric motors, the stored words tumbling forward in a clacking barrage—elicits in me now a keening nostalgia for sitting at what passed as our dining room table, as Brooklyn nights gathered outside. Doubtless typing wasn’t so romantic to my roommate when he was home watching Barney Miller behind the closed bedroom door, smoking the sample cigarettes they gave out in the street then to keep you hooked or get you started. Sometimes it woke him up in the middle of the night, and I’d whisper apologies through his door. I spent hardly any time on the lesson plans, trying to squeeze in as much time writing as possible. But thus did the strange novel grow, astonishingly, page upon page compounding upon our dining table.

I was, of course, eager to get out of the apartment too. I’d take the subway—and, appeasing ever-shifting exigencies of time and money, seldom paid the fare. I’ll admit to feeling some niggling shame, but a subway token (emblem of an evergreen, irretrievable New York: brass-colored with a silver bullseye center) cost, if I recall, a dollar, not nothing for someone in my position. So I became adept at hopping turnstiles, perfecting a means of slipping through the gates undetected by the station attendants, who presided in their bulletproof glass booths like abbots in their personal refectories. It was thrilling to be able to get around the city for free, riding to the far-flung polarities of Rockaway, Sheepshead Bay, Pelham Bay Park, as if under new-found power. Unbound from my desk, I’d explore regions of the city so far-flung it was quite possible that denizens of one section had no more idea of the existence of the other than South Seas islanders had of emirs of the Ottoman Empire. In warmer weather, I’d bicycle through Prospect Park, sucking in exhaust fumes. Nights speeding down Flatbush, Bedford Avenue, where Ebbetts Field used to stand, past check cashing and pizza joints, Dirty Bud’s Recovery Room, the original Juniors, which staked out the corner of Dekalb and Flatbush like an extravagant, generous-hearted hooker—a thrilling manumission, an avowal of the untempered joy that seized my body, as when I learned to ride on the tar-and-gravel streets of the Boston suburbs of my boyhood. Sometimes I’d run along the pedestrian walk on the Brooklyn Bridge, one of the most dazzling spectacles in the country, gazing out at the Liberty Statue, the Twin Towers, and down at the gray river coursing out to sea. In awe of such moments, one felt genuine patriotism and pride in a country in which it wasn’t always easy to lay claim to such unfashionable feelings.

To be poor in New York is to be forever looking in at a rarefied and glittering bubble, a gilded shelter; but the vantage of the poor can sometimes afford the greater prospect, I like to think: the perspective of a threadbare god. The booth of the movie theater where I worked faced 7th Avenue; from this angle a ticket seller would look out at the steady procession of pedestrians strolling by, some of whom would stop and talk to us through the intercom. The wealthy, the destitute, the lost… the intercom amplified their voices over the street’s jabber and strife, as if petitioning a convenient deity. One guy, a regular, a small conspiratorial man in a suit jacket three times too big for him and his few remaining teeth situated far back in his mouth, had been, he said, a trumpeter in a famous jazz combo decades ago. Hard times had befallen him, he didn’t have to say. He’d regale us with stories of long-defunct jazz clubs, Chet Baker, Ellington. Then you’d see him around town sometimes, telling the same stories to people who could turn their backs to him.

A coworker of mine, the son of an actor you’d recognize from tv and a few movies, was always bowled over at characters like this. He’d grown up in New York, presumably, but for some reason the New York scenes and characters he must have been around since birth remained forever novel, his capacity for astonishment perennially refreshed. Look at that guy, he’d say, clamping his forehead with his hand. Can you believe it? Over and over again. Look at that guy. He was right, of course. There were characters in New York. There were always people of all kinds to look at. One night after the movie had been playing a while, Bob Dylan came in with Merry Clayton, the singer of the indelible Rape, murder… line in the Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter. Dylan must have been in a down phase, musically speaking; he looked like he was trying to keep up, fashion-wise.

Still, there are few people more universally Dylan-like than Dylan; and in the middle of the movie he wandered into the lobby, his eyes even in repose had a wary, quicksilver flash of a fox’s with a chicken in its jaws. I thought to say something to him, talk to him like I was talking through the window in the ticket booth, but didn’t see the point.

Everything you had to know about him, I figured, you already got from the songs and the cowboy boots he was wearing. Before the movie finished, he and Merry Clayton slipped out. Susan Sontag, Bill Murray, other music and literature and movie people also came in sometimes, but my life was peripheral to all that then, it was starting out on its own course, and would, I hope, find its way too.

My boss at the cinema later became a pretty well-known film critic. The two of us would go together to broken-down theaters near Times Square, the Upper West Side and the Village. They smelled in those days, universally, of dereliction and pee, and showed scratched-up prints of old John Wayne westerns, Bergman, the standard Fassbinder or Goddard or Buñuel repertory. The ticket takers, seen-it-all boys my age, or gray Beat eminences, ran fingers down their lists before admitting us. In one such palace, around 42nd Street, a glum joint that sometimes screened porn, we watched a movie that was to become a personal favorite. The Last Picture Show. If you haven’t seen it, do. The Last Picture Show (1971) yielded a thousand vicarious thrills, mostly to do with the romance of watching lives decompose in a simulacrum of real time. On the screen, the textured Texas wastelands, on the periphery of civilization, showed an America forever endangered, intended to be plowed under. It was in The Last Picture Show that I heard Hank Williams for the first time, singing “I Can’t Help It If I’m Still In Love With You” as if from a new grave. In Picture Show’s landscape, doors were always rattling on loose hinges. Tumbleweeds cartwheeled in dust-blown streets. In one scene, arguably one of the most affecting in the history of American cinema, a gym teacher’s wife (Cloris Leachman) confronts her high-school age lover (Timothy Bottoms), who scarcely knows how or where his decency got lost. His eyes hold out hope for redemption he knows can’t be given. Hers is a quintessentially and exclusively American face, like one in a Walker Evans picture, its frayed edges abounding in patriotism. Hurling a coffee pot against a wall, Cloris herself abounds in gestures of love and regret. We wait. Wracked. Rooting for her but thinking, too late, too late. Hank Williams sings. A boy is killed—a narrative jolt that feels precisely right in its recognition that life owes nothing. The lights of the theater come up. We stretch our legs and leave. Outside a glorious spring afternoon. New York suddenly seems small, provincial, its bluster something disagreeable and gratuitous.

I stayed in New York a few months after that. I took another part-time job, tutoring a student on the Upper East Side. It was almost summer, a few nights a week I hopped the Lexington line to an apartment on York and the 90s, where I tutored the girl in English and history; but after a while it became apparent that the tutoring agency that had hired me was a con, I hadn’t received a single check. I left messages that weren’t returned, and ended up in court with a bunch of other duped tutors. The defendant didn’t show, of course; we tutors, having won our case, departed the courtroom single file, having spent yet another day chasing paychecks we knew we’d never get. It didn’t matter. It felt like New York was drifting away, its demonstrations familiar, its conclusions forgone. Since coming here, I’d adored the bleak dispirited cinemas, streets sweetly nourished by perfumes of uptown matrons. But the time was coming. The city had grown wary of sustaining the ambitions it had cultivated in the young people who’d come to it. Notice was being given—local scrip would no longer be redeemable.

Later, after the school year had worn to a close and the yeshiva students all went off to lives they’d be living thereafter, I quit both jobs. I left my roommate to keep the apartment for himself and took a Greyhound cross-country, to California, then flew to Hawaii. I’d only the vaguest plans, but the idea of getting a job somewhere in the tropical line offered the least resistance to castaway fantasies I’d semi-nursed since watching Swiss Family Robinson on tv as a kid. Eventually I got hired by a scuba and fishing shop on a harbor on the outskirts of Kailua-Kona, on the Big Island. South Pacific trades wafted from the ocean, criss-crossing lava fields and a too-ambitious parking lot that belonged to the strip-mallish conglomeration of buildings where I worked. Here I could write for long stretches, interrupted only by the few straggling tourists looking for recommendations on tuna and marlin rigs or cheap snorkel gear for the kids.

My novel of Thomas Leroix, the disaffected Confederate creature, was almost a thousand pages by this time. But still no closer to being finished, I was afraid. We’d been together, the obsessive, reclusive Leroix and I, two or three years, I was his eager valet, carrying his hat and dueling pistols. Responsible for his dinners and despairs. We’d both managed to find ourselves in unexpected precincts—him in Kansas, me in Kona—looking for denouement. In my Ali’i Drive apartment, geckos scaled the screens like mountain climbers, munching palmetto bugs, and I woke no roommate, disturbed no lovers in adjoining rooms. Only the nocturnal geckos were there to regard me—their skeptical eyes and chops that would have munched me too if they could.

Tropical nights, fragrant of banana plants, oceans, night-blooming jasmine, came and went in splendid uniformity. It rained only at night, so it seemed, great sky-cleansing tempests hammering the tin roofs of nearby houses. Then the mornings reposed in rainless luxury, the lava fields dried before the sun was fully risen. New York, half a world away, never did exist in Kailua-Kona’s consciousness, I thought. The islands were geological in reasoning, massive active volcanos plunging seven thousand feet to the bottom of the Pacific, and pressed no immediate demands upon a writer, culturally speaking, as Brooklyn had. The images I was trying to summon—the Civil War’s splurge of carnage, Thomas Leroix’s regiment trudging along a mountain ridge, half-buried corpses exposed by the rain—had no analog in the lava and banyan and coconut palms.

Stranded upon a shore far from the East River, staring out to another sea, I could work with little mental interruption. “God keep me from ever completing anything,” says Ishmael/Melville in Moby-Dick. “This whole book is but a draught – nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!” Aye, but the least one is ever offered is a draft of a life, a draft of a draft, before the words drift away upon the trades.