A brief look at the untold riches of cocktail literature.

When Prohibition in America ended on Tuesday, December 5, 1933, at precisely 4:31 pm, almost overnight the drinking public decamped from backrooms and speakeasies into suddenly plentiful public taverns and opulent supper clubs. After thirteen years of being relegated to bathtub gin concoctions, the cocktail was poised to reestablish its former glory.

At the same time, liquor-related literature started making its own comeback. Liquor had always been a staple literary subject. More than 25 liquor-related titles had been published during the cocktail’s first Golden Age, between the mid 1800s and Prohibition. The first of these, The Bon Vivants Companion-or-How To Mix Drinks, by Professor Jerry Thomas appeared in 1862, the last, Hugo R. Ensslin’s Recipes For Mixed Drinks, in 1917.

During Prohibition, drink manuals came mostly from Europe, such as Harry Craddock’s epic Savoy Cocktail Book (1930), featuring recipes from London’s Savoy Hotel bar, and Harry McElhone’s mischievous Barflies and Cocktails (1927), which showcased drinks, anecdotes and cartoons from the legendary Harry’s New York Bar, birthplace of the Sidecar, Bloody Mary, Boulevardier, French 75 and more (in continuous operation since 1911, by the way). The few books published in the U.S. consisted, naturally, of manuals on how to circumvent the law and make your own booze.

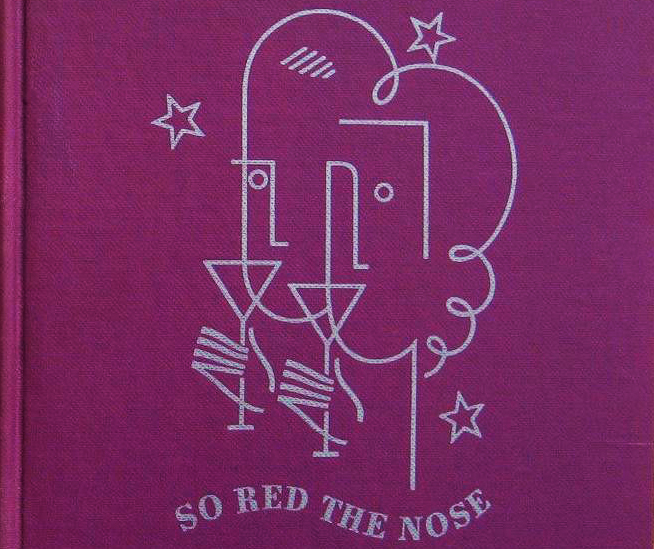

But by 1933, a new wave of cocktail books started showing up on bookstore shelves; between 1933-1935 more of these books were published than during the entire first Golden Age. For the most part, they were written by talented bar owners and tenders. But one of my favorites, So Red The Nose-or-Breath In The Afternoon (Farrah & Rinehart, 1935), features thirty libations presumably concocted and presumably enjoyed by the likes by Ernest Hemingway (of course!), Theodore Dreiser, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Irving Stone, Alexander Woollcott, Erskine Caldwell.

So Red is a time capsule, evocatively illustrated by Roy C. Nelson, whose drawings, done in the post-deco style of Al Hirschfeld, or 30s and 40s Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies cartoons, conjure a time when the past was not so far in the past. Its recipes also tended to run to the gloriously, celebratorily, absurd. Hemingway’s Death In The Afternoon Cocktail comes across as a wtf! joke of a drink –

Pour 1 jigger of Absinth into a champagne glass. Add iced champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink 3 to 5 of these slowly.

But in fact this is a rather legendary Hemingway recipe that’s been on menus since the cocktail revival went into full swing circa 2005.

Is this drink, essentially an Absinthe Highball, any good? Well, if bitter wormwood/anise laced sparkling wine ignites your senses, then by all means, drink three or five. Personally, I enjoy absinthe, especially when it’s ritualistically served by dripping water though a sugar cube that’s been placed on a perforated absinthe spoon.

Dreiser’s American Tragedy Cocktail includes these special ingredients:

1 teaspoon full nitroglycerin

1 treaspoon heavy ground gunpowder

2 jiggers ethel gasoline

1 lighted match

Please accompany the above by horrific series of eccentricities, aversions and drinking habits based upon my notorious and incurable alcoholism. Limit one drink per customer, please, notes Dreiser.

And the Dry Martini pops up again in Kenneth Robert’s Lively Lady:

take a small pitcher with a well rounded interior put in it nine cubes of ice

add four cocktail glasses of gin

add two cocktail glasses of niolly prat vermouth

stir briskly sixty revolutions with a long-handed spoon (the only method which doesn’t bruise the gin)

pour into cocktail glasses

add twist of lemon peel so lemon oil is sprayed on the liquid

repeat until pitcher is empty

Hmm. That’s how I’ve always made my Martinis, although I add a dash of orange bitters, as called for in the original recipes circa 1903-1906. (Note: in old cocktail books, a cocktail or wine glass equals two ounces; a pony is one ounce)

These days writers, perhaps, don’t drink as public performance art half as much as they did eight decades ago. In 2020, we’re more apt to hear about the sobriety of ex-drinkers like James Ellroy and Stephen King than the epic bouts and hangovers of Cheever, Bukowski, Mailer et al. But if So Red ushered the way toward excesses, it also foretold the craft cocktail revival of early twenty-first century.

Speaking of snapshots of time, my copy has an interesting handwritten inscription on the inside cover that I’ll share with you here. I have to translate the cursive Palmer Method, so here goes:

December 25, 1940

Dear Bob,

I pray that this volume will take its place with the rest of the valued works you prize so highly.

This is by no mere collection of story tellers nor anthologies of verse, but a practicable, workable affair used by those of modern epicurean tastes.

I pray for you, brother.

Rev. Jay

Brother Cleve has traveled the globe, playing keyboards and spinning records. Fascinated by local spirits, he’s collected innumerable books about cocktails and spirits. He is the Beverage Director at Paris Creperie in Boston, MA, and lectures extensively on cocktails and their histories.