Between 1974 and 1976 Patricia Hearst, UC Berkeley student, scion of the prominent California Hearsts, became the most wanted fugitive in America.

In Southern California, 1947, they were building, they were building department stores, they were building high-rise apartments, affordable ranch houses, the big corporations were building magnificent headquarters in Torrence and Long Beach and factories in the San Fernando, and all around Wilshire Boulevard the pumpjack fields had given way to shops and movie theaters and burger joints with immaculate green and orange signs with jazzy calligraphy, and all the buildings were gradients of white that merged as a single hue at precisely 4:30 pm when the sun was highest, they were building the Arroyo Seco Parkway following an old riverbed and uncompleted wooden cycleway—a concrete- white swath bearing Paleolithic-looking automobiles from Los Angeles to Pasadena— and there were people going out into the canyons, building houses on the sides of hills, and then on Sundays the ex-GIs and businessmen and the young housewives in the houses would serve little sandwiches and jello-mould salad, with jazz records on the hi-fi, they were attractive young people with bright and modest and fortunate lives, and sometimes you’d see the movie people walking around too, whom you knew right away by their trousers and combed, undefeated looks, or you might spot someone you thought no longer alive, so contained were they by silence and black-and-white—Dorothy Gish, Theda Bara—walking along West Adams Boulevard, looking older but undefeated, still glossy, still endowed with enchanted smiles and photogenic upturned noses, and in those days you could also still go out to the orange and grapefruit groves in San Gabriel, Irvine, San Fernando, forget about Black Dahlia, forget about anything sordid and unspeakable and violent, and consider only the glinting whiteness and symmetrical exemplariness of everything, even the LA courthouse, orderly and modern and a shade of plaster white, where something called the House Un-American Activities Committee was looking into communists, finding them under rocks, finding them in the highest levels of the movie business, but you didn’t always have to think about those things, you could dive into a backyard pool, or take a green sportscar to San Carpoforo or St Orres Creek or Ventura, you could transcend history, its graspingness and futility, you could be in the present of 1947, unlinked to grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents, who came from places like New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, taking a steamship around the Horn, or to Nicaragua, risking the cholera, typhoid, in the crossing, or, a couple generations later the Okies, rubes, coming in freight cars and reefers, looking for jobs in the groves and farms, no, if you were growing up now, in this time, this place, 1947, you might grow into something commensurately prospective, your own future comprised of antiseptic airplane interiors, bougainvillea and monkey flower gardens, the sun upon the flanks of clean white buildings, and upon the parkways and swept-off runways.

Up north, they were logging the redwoods, Douglas fir, they were going into forests two thousand years old, flatcars freighted with 70,000 pounds of timber bound from Tiburon to San Francisco, and the earth was a color of dark blood where the trees had been, and the mud, deeper in color, would slide down scraped-over mountains in sheets, skies aloof, and they would go out from the logging camps to Ten Mile River with their dragsaws and bulldozers and bummer carts and then at night return to the mess halls and dance halls and burned-over land, or you could go back to the century before and they were coming west for gold, argonauts collapsed along the Gila River Trail, defrauded of certainty, or some of them wandering off the gangplanks of packet liners one minute and next on their haunches by a stream, sifting their pans, sluice boxes, and there would be nuggets as big as dog paws, your life transformed, and one who happened to flourish would come overland from Missouri, with an uncanny nose for the cold scent of ore in the bedrock, a man named George Hearst, who would become father of William Randolph Hearst, who would become father of Randolph Apperson Hearst, who would become father of Patricia Campbell Hearst, who one night in February 1974 would be grabbed from her Berkeley apartment on Benvenue Street by three kidnappers, stuffed into the trunk of a 68 Impala, and two months later would be pointing an M1 rifle at baffled customers in Hibernia Bank, San Francisco, robbing it with her own kidnappers, Patty Hearst, Patty Hearst, but in Sutters Mill, California, in earlier days, George Hearst, waiting out the winters, eye on the main chance, could not consider the generational mutations his ambition might wrought, nor consider the kids of the GIs and young housewives, born in 1947, 48, 51, growing up in the houses in the Southern California hills, or houses along US Route 50 in the Missouri lowlands, who’d come to Northern California, driving station wagons, VWs, as newlyweds, students, intellectual speculators—no, George could not see that far in the future and probably nobody can, he could never see Telegraph Avenue or Market Street or Jack London Square in 1974, or the bookstore clerks, graduate students, housepainters, daughters of privilege, sons of teamsters, Sunday school teachers, Camp Fire Girls, 101st Airborne vets, he could not see Patty Hearst smoking pot with her kidnappers, cracking a can of lukewarm beer with William Harris at the drive-in movies, then next day raking a sporting goods store with machine gun fire, rat-rat-rat-rat-rat-rat-rat, twenty, thirty pedestrians diving for cover and Patty Hearst blasting away, picking up another gun and doing it again, rat-rat-rat-rat-rat.

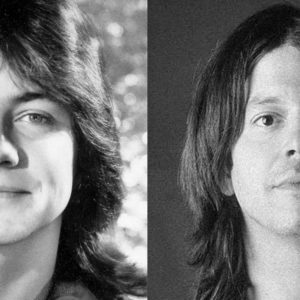

What had been unspeakable was always there of course. Violence was like bad weather that came at once, breaking an extended spell of sunshine. In 1940 at Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street, a corner where cowboy extras used to congregate to wait for the studios to call, one of these extras, leaning against a payphone, pulled out a cowboy pistol and shot another guy in the head in front of about twenty other extras in cowboy outfits. In 1947, the Black Dahlia, so-called, a pretty unremarkable girl with troubles in her background, was dumped in a vacant lot, her body eviscerated as if surgically. The Glamour Girl Slayer… The Freeway Killer… Bobby Kennedy bleeding out on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel…. The stories were covered in every newspaper across the country, especially William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, which never missed a chance to put splashy murder or mayhem on the front page. Then one night in February, 1974 a petite-featured young woman—Angela Atwood, a Kappa Kappa Gamma girl, a girl voted to have most team spirit in high school, newly separated from her husband of a year—would knock on Patricia Hearst’s door, careen into the apartment, followed by William Harris (b 1945) and Donald DeFreeze (b 1943), and Angela (b 1949), would bind Patricia (b 1954) with cord and tape, and as the kidnapping squad sped off with Patty in the trunk of a convertible Impala Donald DeFreeze would fire off a few rounds at nosy neighbors for the fun of it.

In Berkeley, California, in 1974, radicalism as street theater seemed to be running out of steam, Nixon was getting out of Vietnam, Friday and Saturday nights were Partridge Family, Carol Burnett, Love, American Style, sometimes Disney on Sunday. But B-52 bombers were carpet bombing Indochina, people like Donald DeFreeze and Angela Atwood and William Harris were thinking Che Guevara, the revolution’s beau idéal and martyr, was with them, Che in his beautiful beret and fatigues was guiding them.

“Pigs,” Angela would say.

“Dig, assassination’s a political act, right, like holding a sign, only what are people going to pay attention to,” Donald DeFreeze said.

“Theoretically, the question is always about ends justifying the means,” Patty would say.

Patty came from central casting, the rebel girl, sharp-angled, with wary eyes passed down through the two Randolphs direct from George that watched the college-age revolutionaries, the communal chili pot boiling over, her mouth uncommitted. She had a mercurial quick-learning quality, when they unloosened the cords and took the racquetball ball out of her mouth she would speak with the hum-drum rhythm of someone used to lazily wielding authority. They would come across her cross-legged on the floor, they would find her reading the notebooks, manifestos, studying, puzzling over a matter of revolutionary decorum. She had questions, curiosity, Donald DeFreeze was wary, he didn’t trust her bullshit, he threatened to kill her, tested her. He told her about prisons, and the way systems were in place that a white shit girl didn’t even know were systems. A white girl didn’t know shit. He showed her how to hold a rifle, how to stand straight, how to kneel like a soldier in a real army. He let her shoot an M1, AR-80, she could hit a soup can at a hundred yards, better than William Harris, the Marine marksman, she could relate.

“My family is bourgeois,” she said one morning after sleeping all night tied up on the floor. “Everything and everyone I knew was bourgeois.”

It’s a Monday morning, it’s almost 10:00, April 15th, 1974, on the corner of Noriega & 22nd Avenue in San Francisco, and it’s unusually hot, maybe not unusually but hot nonetheless, a thickness in the air. All weekend they had to keep wiggling the antenna to get the channels, the picture was flopping in and out, they were clipping articles from newspapers, taping them to the walls, the rooms are narrow, they slept on mattresses, wherever, even fucking had a recurring obligatoriness to partners who smelled of onion powder and b.o. When they pull to the curb that Monday—DeFreeze, Camilla Hall, Nancy Ling Perry, Patricia Soltysik—DeFreeze tugs a girl’s hat over his head, like he’s robbing banks since he was six, and you’ve got your hand on the gunstock, this calamity in your throat, and to Patty Hearst all the tellers and customers looked the same, only the guards in unpressed uniforms were different. She saw herself in the security camera lens, she was Patty Hearst, aka Tania, Patricia, in wig, a revolutionary jacket, undernourished, maybe starved, the angles of her face steeper, brandishing the rifle, her voice of authority trying not to ebb. The videotape would show: she moves jerkily, her mouth moving. In less than five minutes it’s over, there’s a quick jab of automatic weapon fire, k-k-k-k, like that, Donald DeFreeze’s modified M-1 takes down a couple pedestrians, the blood splotches the material of their shirtsleeves, they’ve got $11,000, they drive away like they won the World Series.

In Southern California, 1974, the light is different, a gray of tarmacs, the gravity is different, they take the Cabrillo Highway, Tania in the back between Willie Wolfe (b 51) and Nancy Ling Perry (b 47), through San Simeon, passing near the castle where Marion Davies’ (b 1897) baroque fantasies spun in the cooling mountain air, the car feels weightless beneath them, insubstantial, they’re taking the Santa Monica Freeway west to the new house in LA, East 54th, Central Alameda, unpack laundry, dishes, notebooks, the black-and-white tv, like distracted graduate students. Plus rifles. Shotguns. Handguns. The neighborhood is shabby, like a graduate student’s dream of shabby, bittersweet vines grow through the links of the chainlink fence, styrofoam cups skidding along the street, you don’t register it any more than you register your own being, they are out one day, Tania and William and Emily Harris, bored out of their minds cruising Los Angeles in 1974, and Tania, left like a pet in the car as the couple shops, keys in the ignition, her mind decoupled, twirls her hair, waiting, her lips practicing a kiss in deference to the windshield’s reflection, there are wadded-up hamburger wrappers on the floor, a couple weapons, there were always guns, incidental tools of the ongoing revolution, then across the street William Harris is punching a store clerk on the sidewalk, Emily on the clerk’s back, Tania is trained in marksmanship, of course, but never shot one in defense of the revolution, and it’s unremarkable, almost, how your life sometimes becomes ensnared in presentness—thoroughly prepared for an unanticipated moment—she loved Willie Wolfe with his name like a cartoon character, friendly tongue in the corner of his mouth, everyone in the Army loved someone, they could love in profusion, Bill loved Emily, and Patricia Soltysik loved DeFreeze, and Patricia Soltysik loved Camilla Hall, and Nancy Ling Perry loved DeFreeze, and Angela Atwood loved Bill Harris, and Emily Harris loved a woman she met in a bowling alley, and Tania loved Willie Wolfe, she carried the immensity of love in her, the way he could be shy, then boastful in a way that was shy, his forearms slender, and the trigger could become an expression of love, an epiphany and an expression of not being petty, of not caring about the things she’d always been taught to care about.

“I am in my nature a creature of careful righteousness,” she once had said. “I am a student,” she said.

The plate glass shatters above the heads of diving bourgeois strollers.

William Harris has a handcuff around his wrist, and the clerk, twenty-something with a wiffle, returns fire, and Tania returns at him, and it’s like the movies only she’s the movie.

This was how you acted in accordance with laws of inferential statistics, revolutions were incited in coffee houses, streetcorners, campuses, why not theirs, America as Yugoslavia or Cuba or Congo or Russia, DeFreeze as Lenin/Tito/Che, they drove around all afternoon, just driving, the license plate number must have been on every cop’s dashboard in LA, there was a used Econoline for sale in front of a house, black, and William Harris pointed an M-1 at the kid selling it and said, Welcome, we’re the Symbionese Liberation Army, surprise, you’re a prisoner of war, William and Emily and Tania and the kid with a rifle barrel at his head headed off to the Century Drive-In, Inglewood, the four of them craning their necks in the Econoline to see Stacy Keach, the actor, in Cinerama. For the record, The New Centurions was playing. For the record, the kid’s name was Tom Matthews. For the record, Emily went out to get burgers for everyone at the concession, the Los Angeles night pulsing with stars. Tania liked Tom Matthews—he was a high school first baseman, above-average student, had a serious serious girlfriend, he said, he was like boys she’d known in school, eager, amiable, a little simple—and Tania loved Tom Matthews with the force of revelation and perfect conviction, the smell of his cramped bedroom still on him. They touched hands in the back of the van while they ate their hamburgers, and she didn’t know why but she told him about the sound of the plate glass shattering on the pavement and the freaked-out pedestrians, as if he might understand. George Hearst had been first and foremost a man with faith in the idea that force applied to a problem yielded results inevitably, and Tania too had known how to apply force, how to compete and come out on top, tennis, shooting, she was never one to do as she was told. When they left Tom Matthews around the corner from his house with a story to tell it was around 7 am, in time for his baseball game, he was just a kid walking down a street, waving so-long. Tania waved stalwartly. Emily Harris found them a motel, across from Disneyland, till things settled down and they could decide. From their room they could see the gates and the ersatz turrets of the Cinderella castle. The room was as comfortable as you would think, with tv and air conditioning.

The Harrises used to like tv, college basketball, the Partridge Family, things like that, they liked the clutter of voices and goofy ramshackle shows. William switched it on. Tania sat on the edge of the bed, finishing her burger, which she’d forgotten about when talking to Tom Matthews. She could fall asleep in a second.

“What you are seeing now is LAPD surrounding a yellow house with white trim, where Patricia Hearst may be.”

She heard the old name, and felt, what?, shame, curiosity, self-dissociation.

It was the first time in history something like this was broadcast live on national tv, cameramen with their minicams ducking behind parked cars, cables as thick as mambas criss-crossing Compton and East 54th. Reporters in polkadot shirts narrating into mics.

William Harris heaved a clock, making a hole in the plasterboard wall. Tania might have gone outside, pacing between cars in the parking lot, before Emily took her hand.

William Harris aimed a pistol at the tv. On tv, the cops were ducking behind cars, hoisting a little black girl over a chainlink fence. They were shooting at the yellow house with the white shutters without relenting. Semi-automatics, service revolvers. It was already past the time of giving up for everyone inside. The cops were too riled up not to shoot the first moving thing they saw in a door or a window. Nancy Ling Perry was shot, a reporter said. Camilla Hall was shot in the forehead, Angela pulled Camilla’s body inside, the reporter said. Inside the yellow house DeFreeze would have been tipping over couches, tipping over the refrigerator for a shield, in ludicrous belief they could shoot their way past five hundred LAPD cops. It was beyond the point of penitence. Tania and the Harrises would know that for a fact. The cops were going round back of the house, by the backyard with the rusted barbecue grill with a broken wheel where Tania and Willie the Wolf cooked hotdogs and squirted ketchup on each other’s bare arms. William Harris tried different channels, as if it might change what they were seeing. He waved the pistol near Tania. William Harris said get in the van, get in the fucking van, they were fucking going to join their camaradas, they could be there in an hour, maybe forty-five minutes. On the tv there were teargas canisters, spurts of flame.

There was black smoke in the white sky.

“I am in a state of what-not,” she used to say when she was a child, not knowing what she meant. “I am in a state of being the best girl.”

It was long ago.

Willie the Wolf, his tongue like a cartoon character, had spread the ketchup across her arm, and licked it off, and they fell into the grass, laughing, lighting up a joint. Now they were driving, the lonesome country songs came on the AM stations like someone else’s memories, she rolled down the window, wind slipping across her face, drying her lips, and she could see herself as someone who was easy in her relation to the world, who understood things without having to tear them apart. In the beginning, out of self- preservation, she kept her loathing of DeFreeze (she was loathe to call him the silly made-up name of General Cinque) to herself. They’d cut her throat in the name of the revolution, Cinque had said—more than once—slamming the closet door on her. Angela later snuck her a glass for her to pee in. Even she could see that Cinque had been in command of an army collapsing into the expanding sweep of its incoherence. A career prisoner, he had theorized beyond what his mind was capable of, and all that unsubstantiated theorizing had resulted in their suicide by fire. It couldn’t have been otherwise, she whispered to Emily Harris. Tania smoked, tossed the butts out the window. They were taking the old state highways, avoiding Interstates. Sometimes it felt like a vacation. There were billboards for Coppertone, Camel cigarettes, Wall Drug, churches. They saw cactus and canyons, convergences of empty spaces. The more driving they did, the less careful they were becoming. She could walk into a store, pick up Hershey bars, toothpaste, tampax, cigarettes, Coca-Cola, and she’d have forgotten her disguise wig, till after a couple times she didn’t bother with it anymore. People didn’t notice faces, she noticed, they registered elements but were incapable of assembling them. In the passenger seat on their VW, she steadied herself, watching horizons, letting her mind settle into unspeculative introspection. When she was a girl it wasn’t that easy, in the backseat of the green Cadillac that used to take her to school she sometimes felt quite queasy, and once the driver had had to pull over while she leaned out the door. She could calm herself now, block out the commotion. Block out everything.

They were the dead: Angela Atwood and Patricia Soltysik and Camilla Hall and Nancy Ling Perry. And DeFreeze. And Willie the Wolf.

“I live in a constant state of suspended animation,” she said.

“Can anyone imagine their lives,” Emily Harris said in the house outside Scranton where they were living.

They were living in the highest echelons of improvisation now. “Houdini has nothing on us,” said William Harris.

He was starting to let his hair grow, his dense beard coming in like a mountain man’s. There was a light in his brown eyes, and he was even more talkative than his usual non-stop jabbering, especially in the morning, when the Scranton sun hadn’t yet had the pipe dreams crushed out of it.

Tania cut her own hair, applied eyeshadow and lipstick, she was reading Fear of Flying, a bunch of Michener paperbacks they had lying around.

The mud in the yard came right up to the house, and they set out cardboard slabs till they became sloppy and shredded.

They were in purgatory, like Lenin in Galicia, waiting for revolution. Experiencing an anxiety of lower order bourgeois, jejune skies over the tangle of tree branches, waiting for a knock on the door. Patricia Soltysik and Cinque and Camilla Hall and Nancy Ling Perry and Willie Wolfe had been cremated by the LAPD pigs, but Tania and the others were living outside Scranton. They went to the local Giant grocery store in a beat-up pickup, wrote manifestos in the notebooks. They practiced tactics till they were ready for combat against the entire United States armed forces. The Malcolm X Combat Unit of the Symbionese Liberation Army fighting under the banner of the New World Liberation Front, William Harris said. People from California came and slept on the floor, a woman called Wendy Yoshimura, others, and Tania happened to like a hippie housepainter whose name was Steven Soliah, who went jogging in the afternoons in cutoff jeans and t- shirt, he never minded when she beat him in checkers, or if she walked ahead. Jogging together one day, Steven Soliah offered to take her back to Los Angeles or Berkeley. She might think about surrendering, he laughed.

One day a knock did come. William Harris loaded some M-2s, he handed one to Tania. Jehovah’s Witnesses. William talked to the untroubled looking young couple for an hour, maybe more, before accepting the materials, thanking the couple without irony. A traveling salesman came. Sometimes they felt out of sync, they were living in a place and time that wasn’t theirs. People on tv looked different, the actors’ shirts had lapels the size of lilypads, their smiles a performance that was hard to get beyond. In Scranton, gas-loving cars lined up, idling, waiting hours in lines that extended around corners. The old lace mills were empty, the city was hollowed out and echoed in its depletion of human striving.

A revolution needs funding. Groceries. Black powder. The electric bill. Mimeographing. Back in California, they got precisely $3729 in the Guild Savings and Loan robbery. A couple months later, $15,000 from a bank in Carmichael. In the process of the latter, Emily Harris’s gun went off, a freak accident, and Myrna Opsahl was dead, a middle- aged woman in plastic glasses, wearing a floral dress and low heels, who was depositing money into a church account of all things. Marx said, The proletariat of today enlists science in the battle against the fog of religion. William Harris and Emily Harris and Tania and Steven Soliah jumped into a Firebird, ditched the car a few blocks away, slipped into midmorning traffic in another car.

Time. Time was a variable that could not be accounted for via bourgeois modes of thinking, you had to break free of cant and clocks and coexist with time, not in defiance of it, it could only be achieved through the revolutionary expansion of consciousness, for the real genius of the revolution was that it called for an everlasting putsch against desire, it was calling for you to conform to humankind’s natural state of being—living within time, fulfilling the desire of what you do not even know you are desiring, which is the desire for desirelessness, so you can be free of grasping for property, monogamy, possessions. Revolutions, said Thomas Jefferson, were the natural order, a violent overthrow of the status quo was refreshing, as necessary, as he said, in the political world as storms in the physical. They were a tempest, overturning corrupt, warped, grasping America. They would create a substantial new relationship with time.

Could you entertain the possibility of multiple spirits sharing a single body? Tania painted houses with Steven Soliah, speckling her hands, the hair on her arms, with flecks of yellow, blue, white, she liked watching Steven Soliah up on the ladders, the sun haloing his hair like a Giotto saint, his broad back burnished by a conspiring sun. They planned to bomb police stations, pig cars, rise up to true faith. Steven Soliah would shoot hoops with neighborhood kids at the end of a cul-de-sac, mixing in with the teens and subteens, hitting long hook shots with a shrugging smirk, and Tania and Steven Soliah shopped together at Safeway, laughing at her disguise wig, the way she could move her jaw to diminish her Hearst chin. One day Tania ran across friends from high school. She fished for her sunglasses, but there was no mistaking Patricia Campbell Hearst of Crystal Springs School for Girls, Patricia mumbled, rushed out as the girls stood with their hands at their necklaces.

“Wherever you look for me,” she said, “that’s where I’ll never be.”

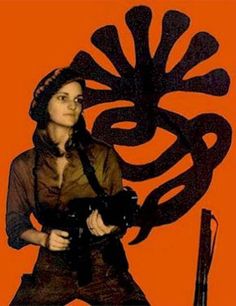

In Southern California, 1975, they were plowing under the orange and grapefruit groves, bulldozing mountaintops, pushing suburbs closer to the edges of the desert, a great mantle of hot asphalt steamrolled down over pastures, wetlands and chaparrals—into San Bernardino, Lakewood, Riverside, Orange County, vast treeless referenceless tracts of real estate—and people were coming from all over for the cheap houses, free sunshine, space age jobs, jobs in the movie business, jobs on military bases, they were coming for a kitchen window that looked out over a concrete patio, and everything seemed to glint simultaneously, as if kept in synch by a meticulous timepiece, beach sand, edges of waves, brand new cars, asphalt, the skin of movie stars, junkyards heaped high with discarded Oldsmobiles and Buicks, and the young families took their station wagons with V-8 motors on weekend trips to the mountains or the beaches, and you could stay overnight on the Queen Mary without ever leaving Long Beach, you could dive under the glinting waves and come up reborn, and by 1975 Nixon had departed the White House, US helicopters hovered like summer dragonflies over the Saigon embassy, and the yellow house on East 54th in LA, where the pigs had murdered their camaradas, was a bare lot, the charred remnants bulldozed into the ground as if it had never been there and as if Patricia Soltysik and Cinque and Camilla Hall, and Nancy Ling Perry and Angela Atwood and Willie Wolfe weren’t martyrs of the revolution, and in Northern California they were turning the old fallout shelters into rec rooms and dens, they were taking over the lumbering parcels in Mendocino, building mansions in the woods, Mario Savio was bartending at the Steppenwolf, and Randy Hearst was offering a $50,000 reward for information that would lead to the return of George Hearst’s great-granddaughter, not knowing she was less than twenty miles away, keeping house with Steven Soliah, the two of them taking turns washing dishes like any modern liberated couple. If it had been George Hearst who had summarized his own generation’s prodigious appetites, men like him who’d come from Missouri farms to erect monuments to themselves, it was George Hearst’s great-granddaughter, or at least the image of her in Fidel shirt and beret, carbine slung over her shoulder, looking like an armed Miami runway model, who seemed to stake a claim to her own generation’s zeitgeist, the difference being that in becoming Tania, Patricia Hearst had been acceding to forces she couldn’t quite imagine, or prevail over. In fact, by September of 1975, the revolution was becoming a little tedious, Patty Hearst was tired of clipping coupons, tired of hamburger casserole. She was playing tennis with Steven Soliah on public courts, she pedaled her bicycle around Precita Park, she saw Young Frankenstein with Steven Soliah at the Geneva Drive-In. The country was getting bored with revolution, maybe even bored with Tania. It was tired of waiting in gas lines and wretched stock market reports. Having exuberance, having flirted with overturning the bourgeois class with some yet-to-be-defined workers’ collective, had brought on a hangover.

They came one day, of course. They were always going to. William and Emily Harris were out jogging—they were from Indiana and they liked sports, fitness—when the FBI came. Patricia Hearst was in the apartment on Morse Street with Wendy Yoshimura when they came. They came up the stairs, two guys in shirtsleeves, and Wendy surrendered.

Wendy Yoshimura was a woman with deep artistic talent. She was born in an internment camp in California, and she used to sleep on the floor of the Pennsylvania farmhouse. In the apartment were a carbine, 12 gauge shotgun, two handguns and a poster of Foxy Brown scotch-taped to the wall. Patricia Hearst ran out the back, then they called her, and she came back, thin lips fiercely braced and giving a clenched fist. Her picture would be on the cover of Time magazine, of course, she would be Tania one last time.