In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the entire country. With bombs. He almost succeeded.

Part One:

The Ballad of Pine Island

A MOMENT

Behind the wheel, he scans the onramps and turn-offs, lines of mailboxes, stuffs himself with fries. The wipers half clear away the moth and grasshopper bodies that have burst in gaudy blots against the windshield. He contains immensities of the land, the noble extent of rivers and bluffs, multitudes of time. He reckons with omens, prophesies.

HISTORY OF MINNESOTA

Time persists, one supposes, without much calculation of its persistence. Twelve thousand years ago, this land was scraped clean by withering glaciers, and the sky was charged in voltaic blue. After a millennia or two, caribou, saber-toothed cats, mastodons, bison started wearing grooved paths in the tundra and spruce forests, the profusion of species giving assurance of their durability. Soon thereafter—a few millennia—bands of Ojibway and Dakota (the Mdewakanton, the Pezihutaziz…) began traveling overland through forests of black ash, elm and silver maple, following rivers and lakeshores, building summer lodges, trapping sturgeon and whitefish in willowbark nets, and spearing the plump mottled pike. In those days French and English traders were also coming up the St Lawrence, canoeing through the churned-up surf of Huron and Gichigami, and up the Bois Brule, portaging to the headwaters of the St Croix. Following smoke threads from village to village, they traded beads, blankets, firearms and brass kettles for beaver and weasel pelts. Soon posts and forts were set up along the rivers, and the baled pelts sent south to the Gulf of Mexico or north and east along the St Lawrence. From the Iroquois reductions in the east, Jesuit missionaries pushed deeper inland, toward the edge of the known world, lank-haired mystic-eyed men in worn black robes and the buckskin vestments of the Iroquois and Huron. The priests, with their squirrel guns and jerked bison and French Bibles, spoke quietly, earnestly, and copied down the words of the tribes. They lived among the Ojibway and Dakota, learning their languages, playing hutanacute with the men, and bartering with the European traders. Soon came even more white men, clearing encampments in the pine forests along the St Croix and Rum, making way for bunkhouses, cookhouses, steam-powered mills and dancehalls.

In north country, along the river valleys, white pine forests flourished in silty loams and glacial tills, going as far as you could see, like a singular green shroud. All day long, fifteen hour days, twenty, two-man teams worked the saws, the sound both far-off and inside your head, snapping branches, surging riotous crashes like the underground rumblings of Hades. Come spring, with the ice thawing and the roads cleared of snow, logs came spilling downriver—in rafts so extensive you could nearly cross the St Croix from the Minnesota to Wisconsin side without touching a foot in the water. Then the camps would be dismantled, the whole operation picked up and moved still deeper into the forests.

Territory constitutes currency; and in 1851 an agreement called the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux transferred ownership of much of Minnesota’s southern and western lands to the United States, effectively ceding Native control to the whites. Seven years later Minnesota officially became a US territory, and, in 1858, a state. In a matter of decades the forests would be cut down, almost wholesale, leaving black stumps and worked-over hills slick with oozing batter-like slurry. The Dakota, the Ojibway and less populous tribes could not be done away with so efficiently.

By 1862, earlier treaties with whites had become irrelevant, at least to government agents, and the Dakota, swindled out of money and provisions, running out of land and options, began raiding white storehouses and villages, escalating resistance until more than two hundred white settlers were killed, and as many taken captive. Houses were burned, children kidnapped, hacked to death. The leader of the insurgency, Little Crow, and his followers moved west to Dakota territory, but, understanding the inexorable force aligned against them, surrendered to armed Minnesota volunteers. Within a week of the surrender, three hundred and three Dakotas had been rounded up and sentenced to be hanged. Back east, Abraham Lincoln, distracted by the Civil War, commuted the sentences of all but thirty-eight. And on December 26, 1862, those thirty-eight were hanged in the largest single-day mass execution in American history. The Minnesota Dakota reservations were shut down, the remaining tribespeople exiled to reservations in the West.

In that same year the only railroad in the state consisted of a measly ten mile track connecting St Paul and St Anthony (part of the future Minneapolis). But by the 1870s and 80s, thirty-one hundred miles of track—eventually absorbed into the Great Northern line—was running north into Duluth and the Mesabi Iron Range, west through the ancient glacial lake basin of the Red River Valley to Minot, Devils Lake, Havre and Spokane. Business interests had always been business interests, and from their inception federal agencies (the General Land Office, Bureau of Indian Affairs) were established to guarantee pacification and domestication of Native people, opening up new territories to immigration, and new sources of revenue to the government. Immigrants from Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany came pouring west via Detroit, Chicago and Davenport, steaming upriver into St Paul to claim their parcels. Initially, the settlements may have been little more than a dry goods store, a tent brothel, a couple sod houses, but the industrious Northern Europeans were soon building new towns, with churches, saloons, banks, schools, orphanages, restaurants, madhouses.

The majority of new arrivals were, denominationally speaking, Lutherans and Calvinists, who were predisposed to a certain commonsensical, rational ecumenicism. But might one suppose such pioneers were also operating with the cultural and religious dexterity of anyone far from home trying to navigate a new land. The circuit-riding mystics of the late nineteenth century, for all their faith-healing and patent medicine pitches, were, after all, bringing news of the land to its newest denizens who’d found themselves, quite wondrously, shipwrecked upon its inland shores. These settlers had come not to revive lives they’d had back home, they were stumbling toward weird new identities, creating a history that eclipsed not just their own, but that of their adopted land.

PINE ISLAND

The town of Pine Island, Minnesota, is reached by US 52, a four lane highway coming up from Charleston, South Carolina, that eventually makes its way through Illinois, Iowa, and the so-called Driftless area, a region geologically defined by natural springs and fishing streams, narrow valleys, bluffs and steep hills left unflattened by ice sheets in the last glacial age. As it stretches north into Minnesota, 52 bisects the state diagonally, tracing old Highway 55 on the way to Fargo, Minot and the Canadian border.

The town itself is situated in the middle fork of the Zumbro River. On 55, south of the Twin Cities, take the County 11 Road exit. It’s quite a small place, population numbering three thousand, with a hardware store, local library, a few barbershops, a mobile home park, a grain elevator, and a performing arts center called the Old Pine Theater that gives it cosmopolitan airs, some might say. In the early days of the twentieth century, Minnesota dairy farmers had been interested almost exclusively in butter and milk production, but Pine Island, set apart from other communities in the state, produced enough cheese—cheddar, Swiss, muenster, Colby—to fancy itself the cheese capital of the world. And as if in demonstration of this fact, one local cheesemaker created a monster three-ton cheddar—four feet six inches high and nineteen feet in circumference, made from the milk of 3300 cows. But in time rural crafts like cheesemaking became economically unviable, a relic of a vaguely embarrassing past, and by the 1960s, sixty percent of the residents were commuting to Rochester and the Twin Cities. But still it’s the kind of small town psychically content in its confinements. A future Nobel Prize winner or Secretary of State, attentive to cosmic vibrations, dreaming of the wide world, may occasionally break the orbit of a town like Pine Island and become something almost impossible to fathom, but lives here are passed mostly in modest employment and pleasures. You might drive to a nearby Indian casino for a spree, or settle into a Saturday night, couple beers, assured of the moment’s constancy and durability.

LUKE

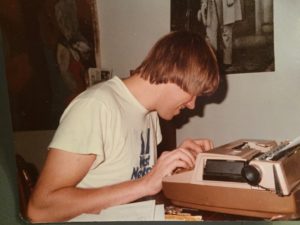

From 1991 to 1999, Lucas John Helder attended Pine Island 5-12 school. He was a middling, pleasant student with nascent artistic interests and a tendency to stick to himself. Five feet, nine, a hundred and sixty-three pounds. Clear skin. Engaging smile that sometimes bespoke a certain lostness, or misty focus. An interested teacher or classmate might have detected something out of the ordinary in his small acts of rebellion, his playing his Discman too loud, tapping his fingers on a desk, but to most kids of Pine Island he mixed in as a good-natured, generic enough friend who would offer a quick saluting wave, and goofy self-deprecating laugh. Darla at Family Hair Styling buzzed his hay-colored hair, emphasizing a hairline that ran perfectly straight across his forehead—the standard jock look. He played Panther football and golf, and hung out at Betty Sue’s Cafe after school. Luke also liked music and liked to pour over CDs at Rochester Records, mostly alternative, and sang in the concert choir. He was into occasional partying, drinking, smoking weed. In summer he performed contraband cannonballs at the municipal pool, and teased his younger sister, Jenna, about her flirting with every single boy on the basketball team. Maybe ten years from now his classmates would have trouble remembering him, but sometimes on the football field now, on the warm August nights that spilled hastily into fast-cooling September, it thrilled him when the cheerleaders shouted his name, which rang out louder than others, he thought, as they clapped and did the splits and performed their choreographed routines. He pretended to be indifferent, but taking off his helmet, squeegeeing sweat from his face, his heart would be going like crazy, and, glancing into the grandstands, he grinned like an idiot at the good fortune that had befallen him. Fifteen Panther cheerleaders levitated as if by some stage trick, kicking their legs in their pleated maroon skirts, and cheered in unison, Luuuukke Heeeelder. A cooling breeze came across the Zumbro River. Luuuukke Heeeelderrrrr….

Luke and his mother, Pamela, and Jenna and their step-father, Cameron, lived in an A frame out on 515th Street, an unpaved country road four miles from nowhere that twisted through grazing pastures and sparse stands of willow windbreaks. In winters, he waited for the school bus in balls-clenching cold, stamping his feet, trying not to breathe in the arctic air that perforated his throat like icepicks and sucked his pores dry. Sometimes in the morning he’d be slow getting dressed, and ended up walking, or Cameron’d offer him a ride. The Accord always, always, was colder inside than out, and the combined breath of the two of them—the one young, the other made temporarily young by his easygoing affability—frosted the windshield, which they tried clearing off with the meat of their four clenched hands. They let time go by as the Accord negotiated the country roads that rapidly filled in with geometrically flawless drifts, the new snow cresting old banks.

On Friday or Saturday nights Cameron went to the Legion for a beer or two or three. For a Vietnam vet who’d grown up with the protests, the war, Woodstock and all that hippie crap, he had a talent for not getting all righteous or monotonous about his history. Luke could appreciate that. Cameron didn’t treat him like a stepson, nor did he try to pretend he was his actual blood son either. Together they went fishing out at Cannon Falls, Prior Lake, North country, bass, muskies, talking politics, the movies, sports, religion, school, things like that. Agreeably aimless, drifting conversations.

On his graduation night, June 1999, Luke was pretty charged up. When his name was announced, he bounded up on the stage and shook the principal’s hand—a broad robustly mustachioed man he’d had zero interaction with over the last four years—and gazed out at his classmates with a bemused, giddy superiority. He pumped a fist and raised his hands overhead, earning a smattering of applause. Triumphant, he returned to his chair in the H’s, next to Wendy Hertzberg, a big girl with a birthmark that covered half her face. Behind the seniors, in lawn chairs and blankets, parents and friends had spread themselves out across the football field in an array more motley than their corralled progeny. Luke scanned their ranks—their adult faces blunter, duller, scoured of high school daydreams or dopiness—and the entire town of Pine Island seemed to float away, drifting off in its mysterious and impermanent intimacy.

That summer he worked construction alongside Cameron. He wore a hardhat, dayglow vest, and lugged shingles and buckets of nails around construction sites all over Rochester for seven fifty an hour. When he came home his entire body was coated in plaster dust, and an unidentifiable grit filled his pores. As a bonus, Cameron let borrow the Accord, which he took to the pool. He’d been hanging out there with a girl he’d met at a football game a few months ago, a tallish blonde with slim legs, green-blue eyes and a cockeyed pirate face. Irresistibly kissable. Her name was Skylar Cassidy. He would make out with her behind the pool’s cinderblock changing clubhouse, and run his fingers over her riotous breasts under her bathing suit top. It wasn’t just her kooky legs and bitten-down fingernails that made him feel weightless, giddy, but the way she would stop and look into his eyes, as if she were burrowing deep inside a part of him. Her mouth tasted of chocolate milk and chocolate chip cookies and cigarettes, her face was like a holy relic.

Waste of my life, Luke said to her about his construction job, trying to impress her.

I don’t like when you talk like that, she offered.

Well, I’m going to do big things. You’ll see.

Like what?

You’ll see.

He’d started writing songs on the fake Telecaster he bought with his construction money, and sang into the tape recorder in his bedroom. Anxiety/society. Relax/Ex-lax. Alimony/Give me your money. Channeling Kurt Cobain. The Blew EP, Bleach, especially, before the band sold out, pretty much. Before Kurt started looking like a thrift-store Brad Pitt, and before the decent-but-not-the-Nirvana-he-loved Unplugged. At Rochester Records, Luke bought pirated Sub-Pop 45s, Love Buzz, Sliver, from behind the counter from a clerk dressed like an accountant with a single stud in his cheek. He played Sliver incessantly on the Silvertone record player his mother had when she was a kid, the dust collecting on the needle like a tiny animal. Kurt’s wretched longing came through the dust and through the speaker, unmediated, gnarled, it was as if the songs themselves didn’t even exist, Kurt’s howls came from a mysterious well, the way Skylar’s lips and tongue sometimes conveyed the longings of Biblical generations. Maybe someday he could write songs like that that weren’t just songs, he told himself. The greatest convolution/ Brain pollution/ I’ll tell you my solution/ Embrace confusion. He was coming up with rhymes and melodies, bass lines, staccato jabs of snare, a stutter bass drum, his brainwaves were going full force with some secret power he couldn’t control. One afternoon he wrote three complete songs, one, he thought, as good as Negative Creep with its squalls of guitar and Kurt’s self-aware howls. Luke’s own singing was more straightforward than Kurt’s, maybe more melodic, he felt. Still, he was straining to bring the feel of winters around Pine Island into the sound, like earlier Minnesota bands he was reading about (the Replacements, Hüsker Dü, early Soul Asylum), where you heard snow sifting across downtown streets, car horns deadened in frozen snowbanks. When Bob Stinson, the Replacements original guitar player, died of organ failure a few years ago, broken-down and destitute at thirty-five in an apartment grimy with unwashed dishes and heroin apparatus, Luke had written a tribute to him for English class (Bob was so good at being a person from another planet that people on this planet couldn’t play in a band with him) and gotten a B+. He was letting his hair grow out. No longer the ROTC, FCCLA or football jock look.

Lately his and Skyler’s lovemaking had been developing new patterns of inventive versatility. They were on a slab of cardboard in the woods behind her parents’ house. She was on top, and he could count her fillings.

Would you rather time travel to the future or the past, he once said to her.

Will you tell me? she asked.

What?

Past or the future—which one?

Oh, there’s no such thing as time, he said confidently. Past—present is a fiction to tell ourselves to make things make sense. Do you want to get married?

When?

Tomorrow.

I thought you said there’s no such thing as time.

I hate you.

No, she said, yawning, her fillings black and gold deep in the warm cavern of her mouth, I will not. She was still on top.

When?

At home Pamela Helder watched Guiding Light, The Price is Right. She knitted scarves and comforters and baby hats for neighbors and her sister’s kids in Silver Lake. She cooked dishes with Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom soup, and baked cakes made with tomato soup, from Betty Crocker recipes. Sunday dinners after church were roasted chicken, mashed potato, pot roast. As a family, they sometimes took little trips to St Paul, Milwaukee, and Cameron whistled How Much Is That Doggie in the Window, and Pamela held the map in her hands, keeping an eye on the signs. These trips, with their sing-a-longs, Luke and Cameron’s talk about fishing, Jenna’s complaints about boys, were always annoyingly wholesome, but he tolerated them, at least their family didn’t fight, or the fights were sublimated.

One day Skylar showed up at Eric Upgood’s wearing dense blue eye shadow plastered over her latticed lids, like paint worn into battle. Her long hair was cut in artlessly girly bangs, the blond tips dyed blue. A candle-like scent came from her skin, an ethereal easy-going essence that messed with Luke’s considerable powers of concentration. The band practiced in the basement of Eric’s house, and Skyler had been coming along to hang out there a lot, like their very own Yoko, sitting cross-legged in a gigantic beanbag, reading a comic book and every once in a while casting a beatifically absent look from her blue-shadowed eyes. It’s a story how I’m supposed to feel because you told me to, Luke sang into the mic, pouring himself into the words, closing his eyes and letting the jagged chords tumble out of him, Bm, C, D, Em, F sharp diminished, his fingers finding notes he’d struggled to find a couple weeks before. It’s a rare wind when the time comes, a never ending train. Run away, run away, he sang, and when the other guys came pounding up behind him with bashing cymbals and Eric’s fingers running up and down the bass’s frets, he could feel something real coming together. Like it must have been when Kurt and Krist got together. Unlike Yoko, Skyler was their good-luck charm. On days she wasn’t around his mind wandered, he’d be missing her legs, her tight narrow bum, caustic breath, the blue gaze. But he admonished himself to not get too tied down, not to let himself give into feelings that got in the way of his vision. They talked for hours about how Kurt would have ended up a car mechanic if he hadn’t made it as a musician, about Luke’s own chances of being a real musician. She listened with encouraging intensity, asking about Aberdeen, Kurt’s influences, that kind of thing, her breathing matching his, as if any little conversation between them might spark wildfire.

In September, his mother, Cameron and Jenna crowded into the Accord, and drove an hour and a half to the University of Wisconsin-Stout, singing This Land Is My Land and Love Shack all the way, like they were taking one of their family trips. In the dorm Luke introduced himself to Matt, his roommate, who was a big easeful guy, wide shoulders, mischievous dimpled grin, with a born salesman’s genius for making you feel every word you spoke was solid gold. Easy to like, he could have been a logger or a gym teacher, Luke thought. If he didn’t exactly fit Luke’s typical friend profile so what, the two of them quickly became friends, going to North Point for dinner, pigging out on burritos and pepperoni pizza, talking about Matt’s family back in Kenosha, cars, girls, fishing, football, and Luke telling him about his own football exploits, which seemed a million years ago. In their room, Luke tried new out songs out on Matt, strumming the Tele, while Matt, highlighting his marketing textbook, tapped his foot in approval or, more often, tendering a baffled earnest look that showed he wanted to understand. In the scheme of things Stout may have been a lower tier school, but Luke truly admired his professors, who seemed to him shrewd manipulators of their inmost thoughts, which were then presented for public benefit. He was taking Intro to Art and Design, Ceramics I, Philosophy of Religion, American Cinema, Fly Fishing. Dutifully he filled his notebooks with unbroken lines of notes, asked questions and speaking up with gathering self-assurance and a sense of his own powers of articulation. He stayed up late reading, finishing papers, smoking doobies, taking in information he’d had only the dimmest awareness of six months before. He absorbed the intricacies of glazing and firing, class struggle, national/cultural identity, gender and sexuality in movies etc etc. Even in fly fishing class, he was learning about conservation practices, and lately had come to the revelation that the muskies he’d caught with Cameron, swimming along the unshadowed bottoms of frigid northern lakes, must have been as covetous of their own existence as he was of his. He even met a couple cute Stout girls who were spiritually, politically nimble (there was a knowing carnality in their absolution of Bill Clinton in the Monica affair), that made him forget Skylar for the moment.

In some ways Stout was an institution like the church, he told Matt from his top bunk, with its orderliness and hierarchies of priests and nuns and diocesan bishops and monsignors and cardinals, with the beautifully martyred Christ and the beautifully virtuous Mary at its cultish center. Only at Stout instead of monsignors and cardinals there were deans and professors and TA’s and campus police. Instead of Christ and Mary at the center there were beautiful books and classrooms and ideas, he said.

I love you, dude, said Matt.

Don’t people have to believe in something? Luke asked. Otherwise, what’s the point.

Asking the wrong guy.

Lately Matt had been hanging out with friends of his from business, and Luke, left to his own devices, found himself eating alone at Commons—Stout’s other cafeteria across campus—eyeing the students who looked so assured in their goofing off and preening earnestness. He couldn’t imagine he could ever be like them, easy and loose and witlessly amiable in their friendships. Homesickness sometimes took Luke by surprise. To ease the dull spasm of it he’d get a Greyhound back home.

Of course a guy like Matt wouldn’t understand. Looking out the bus’s window at the concrete strands of highway, the gray unmowed no-mans-land of the median strips with their staggered Sumacs and effluvia of shredded truck tires and fast-food wrappers and the occasional mattress or a baby seat shed from onrushing, overburdened vehicles, he wondered if he himself had ever been capable of mastering anything as pitiless as faith. Did the people in the cars—these strangers, families, couples, delivery people, salesmen, with their unfathomable inner lives, their tumult and misgivings and spasms of love—ever make peace with faith, their souls no longer contending with powers greater than their doubts?

Back home a few of the old rituals did give him comfort. Sometimes when he was home the band would get together in Eric’s basement, almost as if he’d never left. Then he’d take Skyler out to the movies like in old days, and cruise aimlessly in Cameron’s Accord, past the high school, down by the mucky Zumbro, considering the landscape’s old and familiar assertions. More and more, however, he holed up in his old room, and locked the door behind him. He cradled the Tele, strumming the same chords over and over, content with a single droning C major. He’d sleep late, noon, one, two, using up time he didn’t know what to do with. Not long ago, he’d been sitting in the Old Pine balcony with Skylar, sucking pieces of popcorn from her lips—their love playing out as love was supposed to—but sometimes when she called the house these days, her lulling sexiness and sudden enthusiasms filling the space in his ear like the sea-moan of a seashell, he ended their conversations abruptly, more content with the Tele and the room’s commiserative shadows.

One morning—or was it afternoon already?—he was half asleep when a disembodied commotion, like the clang of a train bell, startled him. Something very odd, or at least not explicable (there were no trains within miles). He yawned, and watched some shadows playing across the yellow-papered wall of his room that looked like old men dressed in some type of dark robes, with ropes tied around their waists. Abstractions, hallucinations, spirits, the randomness of shadows? But almost immediately the sun came through his half-open curtains, and the shadows dissipated as mysteriously as they’d come, leaving no sign of what an instant before had been vivid, otherworldly but unmistakeable. He slid the covers down over his chest, and, reaching for the Tele, sitting on the edge of the bed, returned without pause to his previous unhaunted, unbothered state of half slumber, as if whatever he’d just seen, or imagined, or conjured, was nothing more than an interpretive error, a temporary hallucination.

VARIETIES OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE

Luke had been a churchgoer. Meaning, Pamela and Cameron used to take him and Jenna when they were kids to St Michael’s in an effort to civilize them, as much as to impart specific scriptural training. Cameron was a semi-regular churchgoer, but despite his talks to Luke about Christ and Mary and Catholicism’s abundant social goals and its misunderstood history, Luke’s interest remained at most speculative. Even as a kid it had confounded him that anyone could worship a half-dead half-naked son of god (not even the God) or his confusingly virginal, blank-eyed and perhaps frigid mother. Of all the people who ever lived—

They talked about religion a lot when they were fishing. For a while it was their main topic. Christ’s resignation to his fate, Cameron explained, was the scaffolding of the entire church, an entire religious and presumably economic movement that had been gaining inevitable-appearing authority for over two thousand years. You had to respect that, he said.

He cast a line out over a submerged stump, and slowly reeled it in, repeating the action over and over in an undeviating cadence.

Not have—

No, of course, he said. Not have—

Lots of wars because of it, Luke said.

That’s so, said Cameron, pulling in a little brookie.

For a while Luke had been an alter boy in training, to satisfy Cameron. It didn’t last, but Cameron was the type whose faith was in no rush.

Maybe there would have been wars no matter what, Luke said.

You could respect something that started as a bunch of misfits stirring up trouble with the local banks, and became the most successful mass movement in the history of civilization, Cameron said.

Hn pulled the brookie from the stream, six inches, cinched the hook from its upper jaw with his pliers, and set it loose in the shallows. It lingered on the surface an instant, undulating in the murky water, then flicked away. Overhead clouds scudded, the sun on the teasel behind them made it shimmer.

At Stout, Philosophy of Religion met on Wednesday and Friday afternoons, in the basement of one of the oldest buildings on campus. The course’s teacher, Angela Loosig Smith-Andonian, a hip thirtyish assistant professor, had a bright and colloquial way of illustrating her ideas in the air with a chalk nub in her fingers, as if she were writing on an invisible board. Rose-colored eyeshadow dusted her lids, matching her lipstick, a whiff of linden and rhubarb issued from her skin. All semester, around a stained conference table, she led them in discussion of everything from Zoroastrian traditions to modern Christian liberation movements, Islamic and Jewish philosophies, Buddhist social movements, her knowing cigarette-roughened chuckle enlisting them in her worldliness.

In comparison Luke knew that his own brand of old-school Catholicism, or agnosticism or whatever it was, felt tepid, hopelessly provincial and perhaps, in her eyes, a joke. No professor had to tell him that Catholicism was filled with ancient incantations, mumbo-jumbo and gaudy superstition, and in its current incarnation was refuge for provincials like, he hated to say it, Cameron. Anyone could see it was a fairytale, he said one day.

A slight admonishing smile stretched over her delightfully imperfect teeth.

We’re not here to debate that, Luke, she said.

I am, he said, not as impertinently as it probably sounded.

You stand up for yourself, don’t you.

Her thin upper lip came to rest upon a purple-chalk-dust-covered finger.

I just think Christianity survives as an institution only as long as people go along believing literally that a human being was raised from the tomb, he said.

It was his favorite class, she was his favorite teacher.

The Zoroastrian point of view, she explained it one day, was the closest approximation of what he understood the physical planet to be, given what he knew of it, and his sense of what existed on the other side. There were forces in conflict in the world. Call it darkness and light. Asha (the main spiritual force) derived from Ahura Mazda (the uncreated creator Wise Lord) as a force to prevent the force of druj (chaos) from establishing itself. Have a Nice Day as cosmic revelation. Walking around campus, pondering the subtleties of Zoroastrian scripture, he found himself in a trance, going back to the dorm and playing his guitar with a blaze of new chord changes.

Come on, dude, Matt said one night. Maybe turn off the amp or something? he suggested, being practical as he always was. People actually want to like you, you know.

Fuck ‘em, Luke said.

Yeah, yeah. Matt went back to his work. Just passing the message along, he said.

Luke hopped off the bunk, flipped off the amp, hit G sharp minor on the upstroke, B major on the down, picking the chords apart in arpeggiated notes down the neck like a Boston song or something. The gesture seemed immature, and he grinned at Matt with a chastened shrug.

A few nights later he bolted up in his bunk, with a yelp that put an end to the slumbering chanty of Matt’s snoring below.

What’s up, Lukey? Matt called.

Nothing.

Come on, Lucas. Jesus.

Forget it.

Then why did you wake me out up out of a dream about Eleanor Sabelko?

Sometimes I see these figures is all.

What the fuck? I see Eleanor Sabelko in my dreams. Or did before you woke me up, motherfucker.

Thought you’d want to know.

You had a bad dream.

It’s not like a dream. They are coming to see me.

What’s coming to get you? Come on, rock star, get some sleep.