On November 24, 1963, smalltime nightclub operator and sometime underworld figure Jack Ruby walked into a Dallas police station, and shot and killed Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, further obscuring circumstances surrounding Kennedy’s assassination.

LEON

In 1963 Jack Ruby moved along the perimeters of Dallas, corners of the streets and tucked-away corners where you could get something more than the clap for your troubles. Sometimes he moved within the interior: his schemes, his corner surfing, his pepped-up hopped-up way of getting up close, a friendliness that after a while wore you down. He had a way of sneaking up to you with his grin like a mole’s grin. Maybe that was the point. Wearing you out till you just went along, saw his point, came to the Carousel, take your hat off, rye and soda in the back room, couple dames, rimshot, sax blast, met a guy who knew another guy, and you could put it together and come up with a scheme that hadn’t existed. I mean, it was the thing. You hustled, turned sawdust into brass, maybe gold.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

There was another Darrell Wayne Garner. The other Darrell Wayne Garner was thirty-seven, lived in Fort Worth, Dorothy Lane Courts. Whereas I was born in Delta County in 1940 and lived at 1006 North Bishop, Dallas. The mistake is critical to note because I was railroaded as an operator in the Warren Reynolds shooting business, whereas the other Darrel Wayne Garner was getting off scot-free. Dallas’s always been a town of cover-ups, set-ups, but this created another layer of cryptic deformation, warping of identity.

LEON

You played it right in those days, the cops, the mob, you ran your world, they ran theirs. You could be emperor of Commerce Street, people’d say, Hey Jack, How’s it going, Jack, Jack, come here a sec, can I show you such-and-such, looking fine today Jack. One day he comes up, and says, I’ve got new ladies from the bayou who come with tricks Cajuns taught their daughters since Le Grand Dérangement, customers are going to line up past South Ervay Street. Never any funny stuff with Jack. Toast for breakfast (dry) every single morning, walk his dogs, refreshing swim with a bathing cap. Jack Ruby’s charm was he didn’t understand his own charm. He was always trying to prove his charm beyond anyone’s need to be charmed.

BILL DEMAR

Jack went for crooners, magic guys, comedians. Ventriloquists in a pinch. When I got on stage, and Chuck Norwood did the talking, there was a smatter of applause, drunks trying to impress their dates. But you do your fifteen minute routine before the crooner comes out, Blue Velvet, Hello Stranger, Que Sera Sera. All bits. Routines. Besides Chuck Norwood I do Feldon the Frog, the phone routine, tape over the mouth routine: one-night stands, weekly runs, fairgrounds, banquets, conventions. I just happened to be at the Carousel that Saturday night.

CANDY BARR

Don’t ask me about Jack Ruby. That’s verboten.

CLAY SHAW

In New Orleans, the authorities were on the lookout for space and time coincidences, social coherence adding up to a most fantastic truth, or thoroughgoing delusion. Propinquities. First principles says, Deduce a working semblance down to a kernel of the truth. Think about it: if you go on the theory that motive and opportunity add up to proof, then you’ll find summation as creditable. That’s why they came after me. If the CIA, quote unquote, wants the president out of the picture, to protect American interests domestic and international, and a few rogue guys actually go so far as to talk over taking him out with poison darts, a car explosion, a sniper, that doesn’t put any of those guys in a Dallas book depository on November, 22, 1963, or standing behind a tree on a grassy knoll. Nor, even if that president was addicted to showgirls, and palled around with gangsters, and botched the Cuba invasion, does it mean anyone hired Lee Harvey Oswald to kill Kennedy, then hired Jack Ruby to kill Lee Harvey Oswald, and hired Darrel Wayne Garner to kill Warren Reynolds. It doesn’t mean an agent was sent to Betty MacDonald’s cell to smile at her, reassure her, then stick a sock in her mouth and choke her to death, and tie her toreador pants around her neck and make it look like she was a pathetic girl who couldn’t take it anymore. It’s true. The bodies started to add up. Propinquities of the dead. David Ferrie. Reynolds. Dorothy Kilgallen. Lee Bowers. Betty MacDonald. Jim Koethe. Oswald. But then again everyone dies.

BILL DEMAR

We’re all tummlers, all our lives waiting to be the main act. Ruby too.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

In Dallas, everyone was hiding something from everyone. Everyone was knocking on a door.

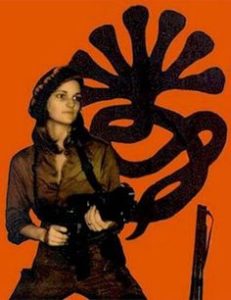

CANDY BARR

All us girls danced the circuit, Omaha, Oklahoma City, Fort Worth, Des Moines, Nashville, Lubbock. A hundred bucks a week, twenty-five a night. You take the two lanes, US85, 54, up through Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas City, roll down the window and wiggle your painted toes in the wind. I picture motels with burgundy curtains. Already the sun’s blanching the macadam parking lot. I picture a little swimming pool out front. Every one the same. I picture a laundromat, your clothes, costumes, pasties, underpants, churning round and round, the laundromats the same also. The cicadas’ chirping, extended on a horizon I can’t see, wears you out, you lay out on the car’s front seat, the radio on low, some old Nat King Cole song you’ve heard a thousand times but this time it reminds you of slow-dancing in the Edna dancehall, your arms around this guy who smelled of cigarettes and steak.

LEON

One generation from the shtetl, Jack grew up in Chicago, Near West side, klezmer up and down Maxwell Street. Nine siblings that lived. Jack was always in and out of foster homes, always looking for a way inside. He undercut the bootleggers, the low-level guys. He peddled tip sheets, took bets on baseball, the horses, a fencing match, you name it. He carried wads of cash, and on account of that a Browning Hi-Power. Loaded.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

I lived out of my car a while, that story’s true. I didn’t always stay at my mother’s, which was a depressing dump. At night we’d drive down Commerce, past the clubs, tossing empties out the window for the thrill. People who lived nocturnally, their eyes adjusted to the gloom and stoplights, senses keen for brakes screeching, a harmonica in an alley. You have to be somewhere. You can’t be nowhere, that’s what always gets you into trouble.

BILL DEMAR

The Carousel, upstairs over the Real Pit BBQ, was always a holdover from vaudeville days, like Jack hadn’t quite caught up to 1963. Lots of the Carousel’s acts were borscht belt guys, their tuxes slick from ten years at Grossingers, Friar Tuck, how you folks doing tonight, I was lost in downtown Dallas today, minding my own business, reading a map at a stoplight a few minutes, before I figured out what a Texas longhorn was. You’d run into all of them. Jan Murray, Irving Kay, Danny Kaye. And the exotic girls. Country girls. Girls with bodies like they were born that way and could never change. Penny Dollar, Jada, Janet Conforto, Tempest Storm, Candy Barr. No one had what you’d call a real home, just the clubs, old beer tacky on the bottom of your shoes, spotlight in your eyes so you couldn’t see past the front row.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

Some nights I’d see Betty MacDonald. She had a few kids early, and her husband was trying to take them from her. I was with her when she bought the toreador pants she eventually hanged herself with. She sashayed in them at Titches; her hips had a doomed assertiveness that gave you a jolt. Was poor Betty dying a coincidence too? Once you start, your mind seeks reason and order and meaning in the absence of meaning. Why the hell should I have shot Warren Reynolds when I barely knew the guy, just because of a fight over a car, or, even stupider, because he saw Lee Harvey Oswald kill a cop? I’m the most innocent guy in the world when it comes to laying a finger on Warren Reynolds.

CANDY BARR

Jack Ruby, I’ll say, was a sweet man. Quiet, but emotional. Excitable, say. He ran on pep pills, hot tea, Pepto-Bismol. Whenever a dancer came down with a case of the clap or a little sniffle he’d bring flowers and soup, give her a peck on the cheek. If customers offered a couple hundred bucks to meet us in rooms, cars, wherever, Jack’d take it outside, beat the guy, kick him in the head till it was like the guy was dead. Sportswriters, beat writers, cops came in the Carousel, helped themselves to beer, Jack’s private stock in back, hustling the cigarette and champagne girls. All Commerce Street was neon then, car horns going off, hustlers, hucksters, pullers. You had the Colonial, the Theater Club. Everyone was always trying to sign up the prettiest girls, the girls with gimmicks like my cowboy set. Jack drove down to New Orleans a couple times a year, scouring the streets and clubs. He had this girl once that could put her legs behind her head. Sixteen, seventeen. He wouldn’t stop talking her up, till one night she drank herself into crying over some guy she left behind, and Jack had to give her an extra couple hundred not to come back.

BILL DEMAR

The history of ventriloquism is as old as the history of hoochie-coochie girls, you know. They used to think you brought up voices of the unliving, conjuring spirits, old ancestors who lived inside you. Eventually ventriloquists ceased being shamen, they mix in the greenroom with the girls and magic acts these days, talking on the payphone to a niece from Palo Alto. There’s a gypsy doing palm reading, or a magician showing card tricks. But there was also something in the air, an atmospheric tension, a sensitivity to the unliving.

CLAY SHAW

Shaws run deep in Louisiana. Tangipahoa Parish. New Orleans. Deep in enforcement of the law. My granddaddy was sheriff, my daddy was a US Marshall. I received medals from three countries in one war. That’s one identity. Clay Bertrand another.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

One day in 62, the other Darrell Wayne Garner quit his job at the aircraft plant, jumped bond, hopped on a bus to New Orleans, took a seat at a bar on Dauphine Street, and who was sitting there but Lee Harvey Oswald.

CLAY SHAW

A narrative through-line that made Jack Ruby, rattling around in his cell, wonder whether he hadn’t been manipulated into being a patsy, doesn’t make it a fact. The day Lee Oswald shot Kennedy I was at an establishment on Magazine Street. Someone snorted— a private laugh meant to be public. Sometimes your life gets linked to a stranger’s, hitherto totally unknown to you. You’re one person one moment, the next everything’s established for you, forces coerce you into an existence of which you’d had no awareness. But it’s you. There’s a car wreck, for example. Or you walk into a room where someone is whispering. What were the witch trials in Salem—evidence compounding into plausible miracles. Fetching water at a well one moment, next the gallows. In 1963, change was dynamic, faster than we could reckon with. I didn’t know my life was being unalterably recast. The narrative goes deeper and deeper, looking for the unsolvable, for the storage locker code that matches numbers scribbled on a wall and the back of a receipt. It’s no wonder. Look. The CIA and FBI were running covert operations, toppling governments, running guns, flying reconnaissance planes with cameras that could click a picture from 65,000 feet up. If you dialed a friend from a phone booth, they could tell if he had a hangnail. Someone decided I was alias Clay Bertrand, aligning the persona of Clay Bertrand, underworld shadow, with Clay Shaw, businessman, playwright, founder of International Trade Mart. Or was I always Clay Bertrand, slipping through the night? The name Clay signaled substance in and around New Orleans. Delta clay of the Mississippi, of Job. Thou hast made me as the clay; and wilt thou bring me into dust again. I ran into Oswald when he was passing out pamphlets on St Charles a few times. He was a tidy nondescript fellow in white shirt and tie. I took the pamphlets, and chatted with him on the corner of Canal. Did that make me Clay Bertrand? Perhaps it did. Or was I looking for myself and finding Clay Bertrand? The first time I saw Jack Ruby he was a blur on the edge of the Dallas police station crowd, a suit and a hat, destined to be that. But if you ask me Jack Ruby wanted to be remembered, Jack Ruby was like Oswald, he had infamy on the brain.

LEON

Jack believed in the religion of American life. November 22, 1963, 11:30 am, on tv, crowds were cheering, Jaqueline Bouvier Kennedy was in a gray suit and matching pillbox hat, he saw her sprayed-stiff and glossy hair, roses in her hand. He saw John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s tanned face and all the hands he was shaking, placards for JFK. 1:40 pm. Jack was watching As the World Turns. His feet were in socks, up on the ottoman. It was interrupted. The tv was saying something he couldn’t understand, as if the words were jumbled. Cronkite. He’d taken an extra pill that morning. His brow was sweating. His thoughts didn’t settle, they kept sparking off his brain like comic book paranoia. You couldn’t imagine John Fitzgerald Kennedy being a person, an actual person who had shaved this morning, fell asleep on the plane, had a bum back, shaking his schmeckle in a men’s room urinal.

CANDY BARR

In the Folly Theater, in Kansas City, signing the Artists Engagement Contract, for work as Exotic Dancers, Exotic Features, and Strip Talking Women, someone brought in a radio. In a store window, they showed the motorcade, the endless loop of Jaqueline, the Connollys, JFK with his wave, almost shy, and then the thing you can’t undo, the instant, you can’t roll back the videotape.

BILL DEMAR

Why not bring in jugglers, clowns, a menagerie. The cops, the mob guys, fraternity boys, conventioneers, guys with dates, you get the sense the whole world comes down to the stage. Saturday night, there was a sign on the Carousel that said closed.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

There were underground guys. Guys who were detectable on some level, undetectable on another level. Like Clay Bertrand. Ruby. George de Mohrenschildt. Lee Oswald. Oswald, for instance. Oswald. Oswald. Oswald. Anyone in certain precincts of New Orleans, Fort Worth, with certain predilections, knew him, you passed him on the streets, heard his voice in your head a few seconds after he was finished talking. One thing people don’t know: the other Darrel Wayne Garner drove to Mexico City with Oswald in a rented Nash, Oswald in the passenger’s seat going on about Havana girls, their skin that smelled of clove and verbena. Oswald was at the Soviet and Cuban embassies, trying to get visas. Then there was a falling out—something about Castro and Oswald’s associates. Garner took off in the Nash, leaving Oswald to ride back on a Mexican bus with a bunch of goats. When he finally got back, Oswald didn’t exactly go underground. On a street corner, he looked like a guy no mother in the world ever wanted, his smile like an orphan smile, he was always trying to fit in. Jack Ruby was another guy who operated on different levels. After Kennedy’s brains got blown out in the back seat of the Lincoln, Ruby was moping around Commerce Street at all hours, like Kennedy was his best friend or something.

GEORGE SENATOR

After the club closed, Jack came into our apartment on South Ewing, watched some Dianah Shore, the Kennedy news, fell asleep on the couch, till the station-off-the-air signal came on. I’d wake him up, get him a blanket, tea.

CLAY SHAW

Do you think the world is more or less interesting than we think?

GEORGE SENATOR

Prosecutors brought up the moral turpitude charges, dancing after hours at the club, Jack’s friendliness with a crowd that sometimes took up the booths in the back of the room. They tore the apartment apart. But who Jack really was was him snoring Sunday morning, still in his suit, hat and .38 Colt on the side table. The dogs made a pile of themselves next to him. The tv came on at five am, the Star Spangled Banner is first thing they play.

LEON

In the old days, the entire world lived on Maxwell Street, Chicago. Mongers, stall men haggling with the shoppers and browsers. Peddler’s two wheeled carts, dogs lapping the cobbles. At the center of it, Jacob Rubenstein with his side businesses, hustles and deals. Hawking kippered herring, live chickens, rotten fruit. Jacob was always moving up. A macher. He sold door-to-door. Vacuum cleaners, shoes, Bibles. Anything. He went for stimulation, the parry and thrust of conversation. He’d spend hours in the back row at Glickman’s Palace, in soupy shadows, they had King Lear, Sholom Aleichem comedies, improvised skits of Jewish girl meets goy eyngl. Plus he worked the door a few nights a week, sometimes a puller, writing his name on the cards to tally customers at the end of the night. He played Fast and Loose, there was a scheme to sell knock-off Shirley Temple dolls, and they’d turn over Sears & Roebuck merchandise without asking how it got where it was. Where he got into trouble was when he sold a shipment of Sears & Roebuck shirts and kitchen goods to a cop, and they beat him up pretty bad, broke his nose, chased him off the street. He spent the war on American bases in the Army Air Forces, fixing planes, before he turned up in Dallas, working as a house man, promotions man, MC, anything but play piano. One thing—he’d always wanted a Cadillac, more than anything, a breathing, alive, champagne metallic DeVille, front seat like a sofa, bumper like a chrome buttress, top down, cruising Commerce Street, stopping in front of the Colony, Montmarte, waving at his customers like Mr Somebody.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

After the assassination half the Cuban exiles and CIA operatives and Soviet spies in Dallas-Fort Worth (and there were hundreds) were scrambling to cover their tracks. Innocent people got caught in the middle and found themselves dead. Betty MacDonald for one. It wouldn’t surprise me if they came for me too.

CLAY SHAW

More propinquities. George de Mohrenschildt, né Jerzy Sergius von Mohrenschildt, was born in the Russian Empire, before the Great War. He fled the Bolsheviks to Poland and thence the United States of America sometime in the Thirties. When he got to the US, he got involved in ladies perfumes, the petroleum business and making documentaries. He got to be friends with bigshots like the Bush and Bouvier families, bounced future first lady Jacqueline on his knee when she was a child, and then in 62, in a twist the most deviant novelist couldn’t concoct, got to know Lee Harvey Oswald through the anti-Soviet underground around Dallas. All the elements came into play: Russia, Cuba, Kennedys, Oswald, revolutions, set off by a guy looking through the scope of his Mannlicher-Carcano from the sixth floor of the Book Depository. I couldn’t recall where I’d heard the name George de Mohrenschildt before. Then I remembered, of course, Comus bal-masque, 59. George introduced himself, wearing a half-fish half-warthog masque, his lips made up in rouge. His accent belonged to a nation caught between warring armies, and he was unremarkable in a stolid avuncular way. I suspected him immediately as an agent. He became friends with Oswald and his wife, visited their apartment. Perhaps both Oswald and George were double agents, freelancers, and neither knew about the other guy. These were guys with ideas that moved them into realms they couldn’t quite control. That’s why Oswald killing Kennedy, then Ruby killing Oswald, must have shocked George. He’d had genuine affection for Oswald. What had he gotten into? At the same time George must have realized that Jack Ruby, whom he must have known through the Cuba gunrunning business, might have wanted to kill him too. Or someone. He—George—was now a prime target, in the realm of time and space coincidences.

DARREL WAYNE GARNER

The mob and CIA hired Darrel Wayne Garner as the obvious and disposable patsy to take out Warren Reynolds. Reynolds knew it wasn’t Oswald who shot Officer J D Tippett, so they tried to kill him. Funny thing: after he almost got killed he changed his mind about who shot Tippet. The Nash motive was misdirection, a shiny object. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Everything was beside the point. There was something happening on the streets of Dallas, in the whole country. Just because nobody could see the whole picture didn’t mean it wasn’t real. Even people involved didn’t know how things fit together, any more than one piece knows the whole puzzle.

GEORGE SENATOR

Jack’s coat got stuck in the door. He had to reopen the door, so it was the last I saw him till I saw him on the tv an hour later.

CLAY SHAW

When George de Mohrenschildt came under suspicion as a friend of Oswald’s, he wrote to me, reminding me of our acquaintance. He asked if I could help get him in touch with someone he could trust with the truth. Truth. He was being followed by the CIA or the FBI, maybe both, he said. He’d be dead before Christmas if he couldn’t find a haven, a new identity. He wrote Jaqueline Kennedy, pleading with her, reminding her he’d been a suitor of her mother and would have married her too, he wrote. Jacqueline would have been his step-daughter. Imagine: little Jacqueline Bouvier, future first lady of the United States of America, feeding Uncle George half a tunafish sandwich on the veranda.

CANDY BARR

I didn’t know whether I was any more Candy Barr than Juanita Dale Slusher, getting the Greyhound at Edna Drug to stay with Aunt Pettigrew in Dallas. Thirteen years old. You find yourself in circumstances. I mean, being something you can’t explain. Fourteen’s young to stand up at the alter, for example, holding a bouquet of carnations, considering the long extent of a life, but buildings, especially tall gray ones, can make you feel in need of a husband. In the motels, with swimming pools outside, I woke up late, feeling the sheets’ scant weight, a feeble sun on the green curtains from behind. My body trying to unresist the day’s undertow. Saturday afternoons are matinees. On stage, bare skin smells of talcum and pear, a synthetic smell in your hair, ghost lines of cigarette smoke twirl in the spotlight. A crowd gathers you, demands you convince it there’s never been a crowd before. No one talks of the news, as they never do, everyone’s eyes over your tits, as if they have power to redeem. If they do, they do. On stage, you think about more than you’d think. Jack Kennedy comes in and out out of my head now. His beauty, the shadow of his lashes, looking at a person from under his lids. Like a forlorn eagle. You think about the Lincoln vanishing under the triple underpass, shining navy-blue, Kennedy waving, looking like the happiest man in the world. The things you can’t undo. That’s one of the things you think about. How once something’s done, the finality breaks your heart. Sunday afternoons are window shopping, looking at mink coats, record players, coffee tables, color tvs. Store to store, the same tvs you follow one to another. Stop a moment, watch in awe. The Jetsons. Disney Wonderful World of Color. Miraculous times we live in. How would it look, a color television in the apartment back in Fort Worth. People can come over and watch. Jacqueline Kennedy’s suit was pink, her hat too. I know that now. Then the police station back in Dallas, black and white again, and the assassin being moved somewhere amidst a clutch of men. Texas men with their white hats, the kind of men at the Carousel, the Colony, their faces ashen with the indoors, their business mouths and certain understanding of authority. Their smell of menthol and dust. A hand comes forward, I know it in an instant. A jerky uncertainty, a need to be. Jack’s wearing the hat I’d twirl at the end of my finger, teasing him. The assassin smirks, as if something hilarious has just been said, and Jack’s body jumps ahead in time, as if spanning decades, as if he’s envisioning every single thing, all the sturm und drang that is to come.