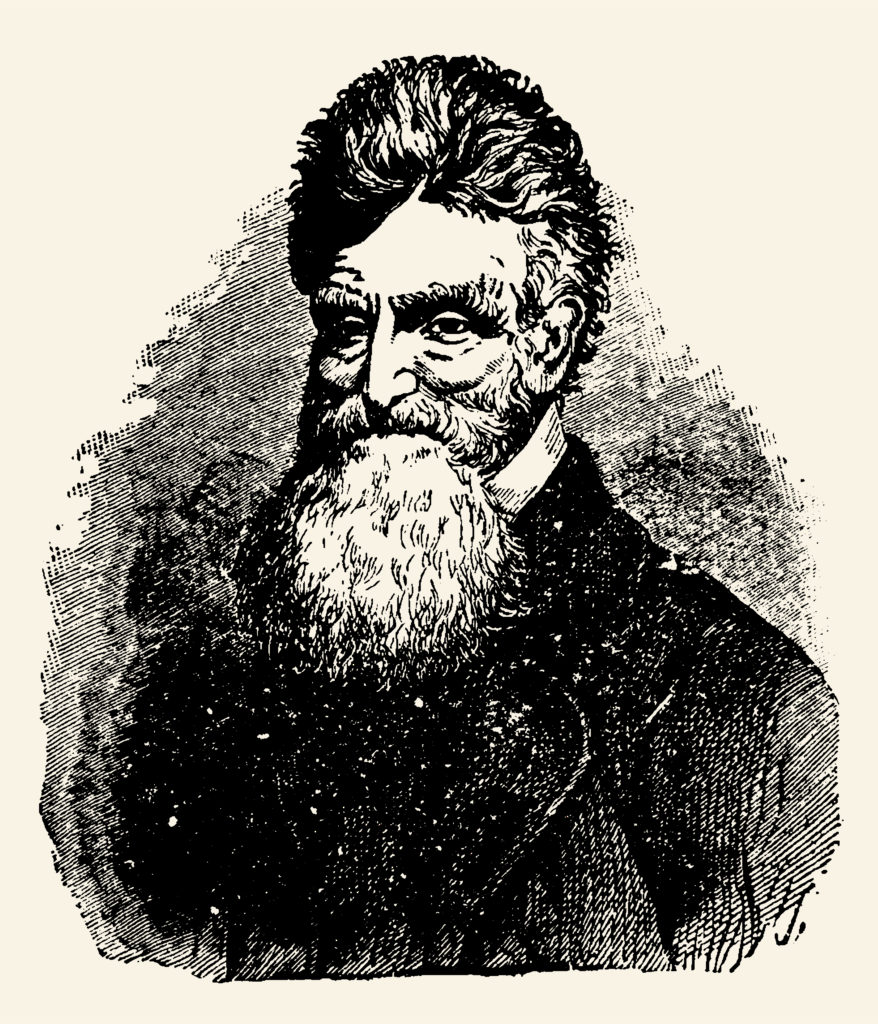

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The events of those days became a prelude to the Civil War.

6:30 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

A prophet ought have many sons, fecund of visions, loins and wars. Nazarene wind he carries in his nostrils, possesses fingernails of clay and embers, carries his beard with the Lord. Prophets heed no influence from mastery of man, temper their souls with no carbon of civilization, they come from deserts where the Joshua tree and sidewinder thrives, word of God in their spleen, armament of swords and brands and pikes arrayed against the legions of enemies. Born of sand and blood of serpents, the prophet girds for eternity.

I, grandson of Captain John Brown, son of Owen Brown, heir of Jacob and Lazarus and the Baptist, taking my commandments from the mount, had six and twenty sons, half dozen daughters, thirteen wives, I came from meager backings, meager houses with three chairs at the table, ceilings so low no beaver hat is worn, working vegetable tanneries on outskirts of towns, the hides of beasts like pages stiff and bloodied on the scales, fumes settling in the winter’s iron temper. In time of the ancient prophets, washerwomen collected buckets of urine for the tanners trade, essence of man giving skin of beasts new life. Outside towns was heard the bleating of the cattle, grunting of the hogs, confused beasts in pens. Thence stripped to skin and meat, becoming tack, shoes, satchels, serving man even unto death. I am 60 years old, having been born to this world on May 9, anno domini 1800.

7:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas

I walk the plains, Kansas territory, Iowa, creeks and poultry yards, sound of body and mind. Whosoever is to suffer is to suffer unto me. I am the enslaved, toiling in fields of cotton, rice plantations, I dedicate myself to their deliverance as if I were them, they me. The Israelite, the Ethiopian, the Indian. All as chattel, but, like me, chattel of our god, not of men.

Those whose war is made on me, so is war wrecked upon them.

8:05 pm, October 16, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

I am grown ancient as the sphinx, in need of rest, folded into hollows where the shoat and lamb lay down in shadows. Ask my God—it is not for me to rest, but fight till my enemies are vanquished. Wagons, loaded in the darkness, start along the Chestnut Grove Road from out of Maryland. We carry Sharps rifles, pikes, provisions for the long campaign, in the darkness oxen chains clink, the twenty-one men of our army snort in their sleeves, muffling their sounds. Guided by the moon’s dim gleaming, light rain, we follow events already determined by providence, follow vectors of our pikes and rifles. Along the road soldiers sing hymns, ditties, and stop to relieve themselves in the woods. Our mules and oxen, riled in their foreknowledge, mutter in low protesting voices, under the scattering stars. In my youth and young fatherhood, I lived in the hills, nomading around Connecticut, New York, Ohio, Missouri, Massachusetts, Iowa, eventually making my living in the wool business, the tanning business, the farming and husbandry business. A wife died in childbirth, and my children, many, likewise, their graves scattered across fields and homesteads in the lowly wind. Why ought I to think of them now, their graves grown over and unmarked? I sense them in the shadows, their voices singing to me from the trees and sky, reminders of a life once lived, but long expired now.

10:30 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

I ride this criminal’s wagon, upon my own casket, nodding at the crowd. The Hebrew Bible tells of the prophet Obadiah, who had forsaken his wealth in service to the prophesies of others. At risk of his own life, he protected the other prophets from the Babylonians and their Edom allies. Though thou exalt thyself as the eagle, says the passage, and though thou set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring thee down. So will it come to pass that other prophets, beyond my time upon earth, will bring down the Southern planters who exalt themselves and corrupt the land with bondage and butchery of human life.

Now I ride upon my own casket, bound in ropes and cuffs, and smile at those who jeer at me, as Christ, bearing the burden of his cross a millennia and half ago, bore the jeers of men, women, children. Let me witness the street vendors and the hurdy-gurdy men, let me witness this carnival one last time.

7:40 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

We steel ourselves, making our minds hard in our work. In cover of darkness, we wait amid fields of bloodroot, spiderwort and the black-eyed susans. The dirt road wends its way down to the creek, where devils sit in cabins by the fires. My sons, Frederick, Owen, Salmon, Oliver, Watson tend the horses, nuzzling them, feeding them sugar cubes by hand. The soldiers of fortune, Thomas Weiner, James Townsley, smoke their pipes, drawing pictures in the dirt with the barrels of their rifles. Our chests breathe deep the chilled night air. Thy will be done. Two days ago in the District of Columbia, Senator Charles Sumner was beaten near to death on floor of the Senate, by a maniac South Carolinian. Sumner is the most exquisite man, handsome and stubborn in his beliefs about the Negro question, and in his speech spoke in stentorian tones of war in this forsaken territory, with its gullies, creeks and scattered settlements. Slavery might be introduced into Kansas, quietly but surely, spoke the senator, without arousing a conflict; that the crocodile egg might be stealthily dropped in the sunburnt soil, there to be hatched unobserved until it sent forth its reptile monster. And for that he was beaten near to death? Man may always chose to fight to the death over a scrap of barren ground, but Kansas land is sacred, fighting for it doubly brutish. The stars tell of affliction, and grow uneasy in the sky.

It’s not too late, says Salmon.

He is nineteen, a lanky youth with a fuzz of beard over his chin and upper lip, a sensitive boy.

It is hard to be so careful, brother, Owen says. But harder still to be righteous. I know myself, he says. I have not learned to be righteous enough.

Owen protects Salmon from vicissitudes, and reads the Bible to him, explaining parts Salmon puzzles over.

Salmon whistles for the screech owl. I wonder what our mother thinks of us, out here at night, he says.

Oliver looks up. He is the youngest, seventeen, and given to swings of mood, a violence that comes, I wager, from such circumstances. He grumbles, paces down the road, impatience rising.

10:35 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

On either side of the street, my wagon passes regiments belonging to our United States government. The townspeople stare, their faces querulous, pinched. The soldiers wear neat blue uniforms, dust on their shoes, they are young, my sons’ ages, mostly, and do not, I apprehend, fully understand their representation of the authority of government, that their lives are given to enforcing that charge. I meet their looks, so they might see the man they will hang. They too are the condemned, the nooses sound around their necks. I ride upon the box that shall be my resting place, rocking to and fro as if on a jaunt in the country.

9:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

Some years ago in Springfield, Massachusetts, I sat in the Sanford Street Free Church, listening to Mr Frederick Douglass. To many, the prospects of the struggle against slavery seem far from cheering, said Mr Douglass. Eminent men, North and South, in church and state, tell us that the omens are all against us, he said. Afterwards I talked to him about the state of the negro in this country, of which he has special knowledge on one hand, but from which he is insulated on the other, surrounded as he is by the white abolitionists. In the community in North Elba, New York, where I lived for a time, I came to know the negro as a friend, and worked to teach the negro families to plant and harvest, and thence in Kansas became Captain Osawatomie Brown of the Pottawatomie Rifles, with an army of a thousand thousand men, who fight for manumission. Tonight we seven men eat our dinner of cornbread and cold joint. We watch the smoke from the chimneys of the Dutch Henry settlements, the devils unaware of our battle plan.

Oliver goes to the wagon, his back straight against the slats. Wake me when the regiment’s ready, he says. He is a good son, honest and good-natured, zestful in fullness of his youth.

10:37 pm, October 16, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Without opposition the men move into position and take the railway bridges, the armory, arsenal and rifle works. By god’s hand the campaign has commenced, and so we act in accordance with god’s word, and with our knowledge of we are about to accomplish. By tomorrow the world shall know of our accomplishment. Here written the demise of negro captivity.

12:02 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

I give the order for a company to be dispatched to the home of Colonel Lewis Washington outside town. A servant in shabby livery opens for the knock, and, making the servant a hostage, one of our men points a Sharps at the head of Colonel Washington, General George Washington’s grandnephew, a tall heavy man in nightshirt who struggles out of his bed to find his carpet slippers. Our detachment commandeers a sword and hilt given General Washington by Frederick the Great, and dueling pistols given by Lafayette, symbols of the fame of our enterprise. The negroes of the estate, unprepared, consider themselves captives, and greet the news of their emancipation with skeptical turn of heads, awaiting additional information.

Upon return to the armory, Oliver says to me, Captain Osawatomie Brown, I present to you the great grandnephew of General George Washington, and these spoils of war. Let war commence according to your wishes, captain.

1:21 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

The common carrier crosses the the bridge above the Potomac, gray smoke pressing from beneath the covered truss, the locomotive’s pulmonary pant coming in the darkness. Watson signals the slowing train to a stop. In the shadows a man leaps down, coming to investigate. This too our army has anticipated.

Shoot him, says Watson.

Oliver holds the Sharps with sure hand. For the sake of men in bondage.

He squeezes the trigger.

So shall it be done, brother.

The man buckles, wedged between the train and bridge timbers. Oliver lowers the Sharps, his unshaved face unrelieved in its stoic appreciation of the scene.

Oliver and Watson wave the train on, so as not to arouse suspicion, it goes westward toward Wheeling, the caboose light vanishing along the tracks like a submarine fish.

A questionable omen: the dead man is a negro.

In the rifle works and armory, the men are cracking open crates of rifles, arms for our army that at this moment is amassing itself in the hills of Maryland and Virginia against the enslavers. Our revolt signals a time when the present shall become history.

2:00 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Colonel Washington, the hostage, begs to see his wife, making promises of keeping silent. And so ought he to fear for his life, for so it is written, And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.

Our tactics are the equal to our strategy.

11:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

There are sounds you do not hear lest you pitch your ear to them: distant yowling of dogs, crickets and cicadas in their exquisite yearnings, the grousing of cattle by the creek bend. There are steps that are taken that cannot be untaken.

10:40 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

I shiver off the chill, trying to shimmy the coat over my shoulder, assisted by the jailer’s hand. What is an instant of comfort in life, in an eternity of sleep? I fear not. I fear not. In this box, I am to join my children, my wife, the ancient ancestors of the desert, pilgrims of exodus, readers of the burning bush. There was a time one winter in North Elba, when the snow was falling outside the windows, we were inside by the fire, there were preserves and hams in the cupboard, our neighbors were the negroes who came, and we sang the old hymns and prayed together and ate supper together. But now that I am to be no more, my thoughts, my memories, my moral fire, must pass on. I only held these things for my allotted days. The gallows are in the field, on a low hill outside town. The structure, made of new timbers, is there in full, mountains behind, white farmhouses in the vast fields, and a bright fall sun warming the grass and leftover stalks of corn. So much ceremony attends the extinguishing of fellow man. The crowds of Virginians, the newspaper writers, tourists, the mounted cavalry and infantry soldiers, sentinels, have come to witness and ensure the last moment of a man’s existence. To make example that one man might not start a war. Wars, howsoever righteous, are started only by authority of government, and under the admonishment of laws.

11:35 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

A door is knocked upon, presently answered by an old woman of forty-five or so, her visage querulous in the light of her oil lamp. Her hair, color of dust, is undone about her head, her mouth disclosing no obligation to sentiment.

Do you know where I might find Dutch Henry’s? I remove my straw hat. Yonder.

She gestures with her eyes, not her head.

Watson and Oliver rush in, scripture quoting, pushing the woman into the table, showing their pistols. She hollers to a man we cannot see, who emerges from a little room off the kitchen, a smallish slaver with pig eyes and slack set of his jaw and shank of hair sprayed over his sweating pate, who sets upon me with fists until Watson holds the Sharps to his head. It is necessary to act swiftly, with improvisation and instinct. Watson ties up the slaver up (his name, we discover, is James) and holds the wife without tying her, a courtesy to an old woman. Five half-sleeping boys come out of the two rooms, a few no more than ten, one almost twenty, I reckon. The oldest pleasant enough looking, a full foot taller than his father, with curled hair like wood shavings and a chin like a judge’s. A gun hammer clicks: Oliver. Never has this boy aimed a gun at anything. His hand is steady. Their mother stares at me without tears, as if my authority could possibly affect the course of events.

I do not speak but wait for my sons to apprehend my meaning.

If our enemies are killed, as in days of Kings, might their sacrifice atone for the sins of those who enslave countless hundreds of thousands, beat them with the cat-o-nine tail, and take their bodies as their own? Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.

The slaver James follows us unresistingly, perhaps curiously, into night air. The three oldest are selected by Watson, who signals for them to follow. Without warning, their mother throws herself at his feet, begging him leave at least the youngest. Brute animal noises are coming from her, and she clings to him, who tries to kick her off, with neither scorn nor care. The boy—youth—is old enough to procreate another generation of dirty slavers—man enough, with wide shoulders, faint mustache—he looms in the doorway without speaking. Unknowing where to go, he might bolt. Watson allows the boy back into the cabin, the two pass in the doorjamb, slightly nodding, their eyes meeting an instant. I watch with no outward protest.

I walk ahead, taking the three remaining down the road, surrounded front and behind by men of our company. God, I am certain, is never more with us than he is at this instant. His eyes are on us. He marches in our company. I pray silently for His sign. James breaks toward a stand of trees, but in an instant Salmon’s upon him, grabs his pantleg and tackles him to the ground. Owen, not far behind, raises the broadsword, coming down upon the slaver’s shoulder, and again upon his leg. James holds up his hand, and another blow is dealt, this time by Salmon, who hacks him around the neck and head, till the slaver sinks down, his breathing slowing. In the darkness, his clothes are blackened, blackness spreading into the shirt’s hollow whiteness. I step forward, feeling nothing, feeling no burden, no grief, no discomposure, no remorse, and remove the pistol from my jacket and in a single motion deliver a single bullet to the slaver’s forehead. I have become who I shall be. The two boys (their names Drury, William) understand everything, they have moments to plead with their god for forgiveness and atone for their sins, naturally they try to run, but my boys seize them too. They are stronger than their father, but we are stronger still.

7:00-10:00 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Armory employees, local Virginians, Marylanders, come in through the gates, and to their confusion are taken immediately as hostages, watched over by Owen, Oliver and Mr Dangerfield Newby, the mulatto, in the engine house. We treat them as we would comrades, talk to them of our plans. Owen, Oliver and Mr Newby engage them in conversation about the insurrection, telling them that negroes, being naturally industrious and good natured, will make good neighbors and friends. Most of them are not slaveholders, they claim, but the slaves are happy in their station. What they do not know is that slaves in the vicinity will have heard the news, and will be joining our army by the hundreds, thousands, equipped with new rifles and more bullets than the Federal army used to fight off the British. This revolution will spontaneously ignite revolutions still more encompassing, these grow into a singular all-consuming war all over the South, devastating the corrupt and benighted regime of the Southern slaveocracy. Outside, the sky brightens, a thin line of yellow creases the river and riverbanks, the bridges and ramshackle collection of buildings that make up this town. It is well nigh upon the time for the arrival of the freed slaves. I order Mr Newby and Watson to the gates to check.

But the moment they are away, an argument is heard, and the tattooing exchange of guns.

I hasten to inspect the source only to find Mr Newby’s body, twisted upon itself, lying in the street, his mild and honorable face turned toward us as if pleading for the great cause. Flies already cluster around his open eyes. His fingers are curled around a staff he’d had with him a moment past. The second casualty of the day. Two negroes. As I stand at the gate, bullets careen off the armory walls, fired by the self-appointed deputies outside.

Negro reinforcements will have to fight their way through these marauding ruffians to reach us, but I have no doubt their determination will see them through.

10:50 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

To be young in this country is to be lost. To be young in this country is to learn the country’s sin. But, fear not, God heeds not the deceiver nor the pirate. Looking upon what I see at this instant, this land might appear unagitated. It is a land of farmers, mechanics, merchants, scriveners, inventors, ministers, fish mongers, husbands and fathers and spinsters, all living in industrious accord. It is a land of mountains and farmyards and the roil of cities. But, mark my words, beneath outward harmony is concealed evil’s portent. My body on the gallows will awaken those who are young. They know the work ahead. The cotton factor, Northern banker, Southern planter, the overseer and driver, will suffer in the war to come. For, as in Scripture, the indignation of the Lord is upon all nations, and his fury upon all their armies: he hath utterly destroyed them, he hath delivered them to the slaughter.

1:00-2:00 pm, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

One hour ago, my son Watson was alive. He was a young man, of average height, nimble in his step, never shy from work, sure of his opinions in the way of young men. Last I saw him in full vigor of his youth, he was offering a prisoner water from a ladle. At my order, he walked outside, past the gate and Mr Newby’s body, under a flag of truce. We wished to negotiate honestly and honorably with the men of Harpers Ferry. Under the flag, Watson was shot. A man aimed and shot him in the chest for no reason other than he was standing there with a flag. He stood an instant, taking stock of his wound and, I like to think, his God, and fell not fifty feet from Mr Newby. We are given no choice but for our war to go on. We will wage it to the last, avenge the deaths of Watson and Mr Newby. A prophet rises beyond the congress of death, and beseeches his God with the resounding thunder of conviction. Yet another young soldier of our army, Bill Leeman, loses nerve, and deserts his post. I watch him slip out from behind the rifle works, and wade into the Potomac for his escape, plunging under the water. I watch his progress through the window of the rifle works with no envy of his freedom. Nor do I think to shoot him. Then the men that shot Watson Brown turn their old muskets and shotguns on Bill, hunting him as if he were game. They would kill him with pitchforks or shovels if they could. Stricken, he stumbles and climbs onto a rock in midstream, holds to it, half submerged, his leaking blood slithering like snakes in the brown river. Outside, still more townspeople are gathering, ragtag militia we could easily defeat if our soldiers did not desert. Finally a decision is made. We leave some prisoners in the rifle works to their own devices; Oliver and I select others to join us in the sanctuary of the engine house, and set an oak beam across the door as a barricade. Outside, for hours, are heard the sounds of dogs and roosters in nearby yards, the muttering and shouting of men. Some authoritative voices offer to negotiate terms of our capitulation, but no victory is won without casting off of one’s fondest garments. There are protracted periods of silence, punctuated by birdcalls and the rivers, the sputtering of bullets.

6:30 am, October 18, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

The Marines mass outside, fixing bayonets with twists of wrists. We regard their serried ranks, uniforms of sky blue, scarlet stripes on their trousers, through chinks in the engine room door. Their whiskerless faces are firm, afraid, in morning’s gloom. It will be said I am a madman, but it’s the madness common with the awfully sane, the heart that seeks to break the husk of earthly constraints. I pull on General Washington’s sabres. I aim at Harpers Ferry mayor and fell him with a single shot, bent bodies heaped in the streets.

Gathering our remaining forces, holding our remaining prisoners, it is right to die with the tender mercies of a madman.

11:00 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

The cadets gaze sidelong toward those assembled for the event, and momentarily glance up at me as I mount the gibbet in my carpet slippers. The hangman’s breath has a whiff of onions and lager, he is of short stature, and wears boots of chapped and dusty leather, and is courteous in expression and movements of his hands. He unloosens my hands, shakes mine, and offers the noose to my head, permitting me accept it in my terms. I stoop in accommodation of the sack, till even the sun is blotted out. Prophets wear the vestments of beasts of the wilderness, skins, feathers and scales, and attire themselves in the whirlwind of their prophesies. Martyrs, in knowledge of eternal life, wear coarsest cloth of creed against their skin, they go down to rivers, cleansing themselves in jubilation and exculpation. All men face eternity, expended in fiercest drive against heavens’ murderous stillness. All men suffer fate of their birth to count down the number of their days. Yea, I have finished counting, and count my death as just endowment in service of those days.

The drumbeat of the drummers grows louder, plaint of rivers, howls of chains.