The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

More

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don’t know.

Apocalypse, noun apoc·a·lypse | \ ə-ˈpä-kə-ˌlips plural: apocalypses

- one of the Jewish and Christian writings of 200 b.c. to a.d. 150 marked by pseudonymity, symbolic imagery, and the expectation of an imminent cosmic cataclysm in which God destroys the ruling powers of evil and raises the righteous to life in a messianic kingdom

- something viewed as a prophetic revelation

- a great disaster

—Merriam-Webster

Naturally, talk of apocalypse is more lively these days than at any time in recent memory. Ends are on everyone’s mind. There are, of course, people who will tell you that such ideas are best left out of enlightened liberal conversation: climate change, racial injustice, political mayhem, unending wars, being human problems with human causes, not something stirred up by a glowering retribution-minded desert god. Yet the conversations keep coming up, and the idea of god as a controlling presence, as an apocalyptic being, literal or metaphoric, is endlessly enticing even in 2020. The twentieth century theologian/ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr, who was always on the lookout for links between verifiable and eternal worlds, put the modern existential implications of the apocalyptic metaphor front and center: The apocalypse, he wrote, “is a mythical expression of the impossible possibility under which all human life stands.” And in some ways, the implications of “mythical expression” in Niebuhr’s framing might be the same for us in the twenty-first century as it was for the early Judaeans who first conceived of apocalyptic imagery: we stare into the cosmos with awe and trembling. Niebuhr’s winking, “impossible possibility,” points to a crossover of hopelessness and hope, the daily duality of the human condition. Life now, as ever, hangs in the balance.

Historically speaking, there have been plenty of apocalypses to go around. For three millennia, give or take, the apocalypse idea drifted in and out of favor, a readily mutable and spiritually resilient shorthand for temporal anxiety, an enduring myth by which existence might somehow be understood as transcending bodily constraints. The franchise, as Niebuhr hints, has always traded in all kinds of dualities: hope and despair, possible and impossible, end and beginning, salvation or damnation, annihilation and rebirth, submission and domination, reality and myth. We sift through these in hopes of finding a mythology apposite to our times. And as apocalypse metaphor de jour, the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is unsettling to us not just because of the havoc it wrecks in our streets, homes, workplaces, performance spaces, schools, stores and old folks homes, but because of its disruption of the habits and social customs that have often offered fellow feeling in other would-be apocalypses. Metaphorically, coronavirus, like the 1918 flu before it, ramifies into a diabolical test of social solidarity. In midst of other catastrophes that have tested our forbearance—in wars, pestilence, genocides, to name a few—physical touch, the glances of strangers on the street, offer countervailing human connection. But coronavirus exaggerates havoc, robbing those who are not felled by it of handshakes, kissing, hugs, the bodily frisson and common cause of everyday life, turning friends and lovers into risk factors, and strangers into vectors of the apocalypse. A few months ago a dear friend’s father, whom she used to visit weekly in a nursing home dementia unit, was diagnosed one day and died the next, and the sight of my friend, virtually alone in a blustery Massachusetts cemetery, her fingertips touching the closed box in the back of the hearse that held her father, was one of the most wrenching sights I’ve seen in my lifetime. Two attendees besides the funeral director at the burial. Our aloneness laid bare, bare—

It was a scene that begged an artist to find small redemption in its humbling dignity. At other times when our purchase on life has suddenly become precarious—during the Black Death, the 1918 flu, the holocaust, the AIDS crisis, say—artists have sought to offer metaphors, a way of shaping our collective understanding of the virulently incomprehensible. In the late Middle Ages, as Black Death swept across Europe and Asia, apocalyptic iconography adorned pulpits, illustrated manuscripts, mosaics and the like. In the pandemic’s earliest stages, the imagery tended toward the punitive, pestilence as an instrument of god’s clearinghouse. Anonymous sinners were cast into fiery pits, decomposing bodies set upon by jowl-licking dogs. Only toward the later stages, with millions already dead (many of whom may have been assumed to be non-sinners) did the imagery become a little more sympathetic, the sufferers and suffering humanized, and the artists’ less obsessed with sending earthly sufferers off to eternal suffering in the afterlife. On the literary front, one of the most well-known books to come out of this period reconsidered the Black Death as an instrument of suffering but also pointed toward human commiseration as counter to human impotence. In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353), a group of young people on the run from the plague entertain each other in a country villa, telling tales that are alternately erotic, heroic and comic. Even in the super-saturatedly religious time, steeped in crippling apocalyptic mythology, the young protagonists sought to create a rich secular life outside familiar tropes of salvation or damnation, with hesitant ambivalence about the origins of “the death dealing pestilence, which, through the operations of heavenly bodies or of our own iniquitous dealings, [was] sent down upon mankind for our correction by the just wrath of God.…”

In our own times, global pandemics, widespread environmental catastrophe, mass unemployment, the shared psychic evisceration of 9/11, neverending racial injustice, a crisis of identity in an increasingly dystopian American scene, has introduced a psychic trauma that seems not far from that of Boccaccio’s protagonists. As a rule, we might feel detached from millennia-old religious beliefs, but as we look into the crystal ball of our collective future we see little reason to believe our terrestrial kingdom can be sustained, and grapple with more than metaphors of mass death. In certain circles, casual conversation turns, almost invariably, to end days, destruction of existing mores, a society facing mortal danger from a virus that invisibly taints the air we breathe, and, in this country, the political party of Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt and Eisenhower being held in thrall to a thuggish simpleton. A redo seems not only just, but gives hope of a future when saner gods might reign.

In the Seth Rogan buddy-cum-end-of-the-world comedy, This is the End (2013), the end in question comes at a party at James Franco’s house as Hollywood partygoers tumble into fiery pits or are sucked up in blue columns that seem to operate like pneumatic tubes used in nineteenth century department stores, leaving Seth, Franco and their buddies behind, self-quarantined in Franco’s modern Xanadu. Modernists with vague religious awareness, for the life of them they can’t quite put together a list of the deadly sins to sort out why they’ve been left behind, and like seventeenth century theologians debate the Holy Trinity and power of god, when Seth suddenly has a stoner epiphany: “I mean it’s like, its like the real apocalypse. It’s like the Book of Revelations. That means there’s a god, right? That there’s a god? I live my life as if there’s a god, but.… Who actually saw that coming—that there’s a god?”

End came out early in Barack Obama’s second term, before the advent of MeToo, but months after the murder of Trayvon Martin, at a time when cynicism and possibility seemed to be struggling for dominion at the edges of America’s ailing frontier. Seen from a much darker 2020, the lesson of End feels quaintly hopeful, decidedly non-Old Testament, non-Trumpian. Care for each other. Don’t be a douche. Maybe there’s a god. Having learned their lesson, the buddies ascend in the blue columns to a dance-party heaven that’s everything a man-child could wish for, certainly not a place, seven years after the movie came out, most of us would consider congruous to our age of racial reckoning and world pandemic, where we’re inclined to regard each other like stunned survivors.

What exactly is an apocalypse anyway? And, by the way, who gets to advance to the next level? As an idea it’s harder to pin down than Webster’s might let on, or we might think of it. The word, Greek in origin (ἀποκάλυψις, apokaluptein), literally means “uncover,” or “revelation,” and the promise of a new beginning. God would flush out an old fallen world and replace it with a new, improved version. Such thinking really started catching on around the time of the Babylonian exile (597 BC – 538 BCE) as captive Judaeans were deported to Babylon. Judaeans had good reason to wonder about god’s promise that their kingdom would last forever. How were they supposed to take god at his word when their kingdom was plundered, their citizens taken away in bonds? An explanation was needed. So if the apocalypse idea came out of what was essentially a contract dispute, and after several millennia of additional contract disputes, one might argue it now accounts for tent revivals, cosmology, dystopian novels, Decameron, reform movements, This is the End, and nowadays what feels like collective anxiety in the declining days of the American moment.

On a secular level—not just god’s—apocalypses have also been political, and known to operate as displays of power, separating deserving from the undeserving. Take America in 2020. Over the course of his White House lease the ostensible leader of the free world has been barely able to maintain a baseline imbecility. By any objective measure he’ll go down as the worst president in history. But—and here is the crux of god’s methods too— the strongman tactics Trump employs with such gloating glee create a state of perpetual terror about our collective hold on the world. This is the End could laugh at it, but here we are— At the instant of pandemic, and collective national self-examination on questions of race and gender equality, the ostensible leader of the free world wades through cleared streets like a third grade bully, incapable of even pantomiming facial expressions beyond scorn and self-congratulation. An apocalypse suits his agenda of wholesale moral and physical destruction. By “making America great again” (that “again” being, perhaps, the most potently loathsome dogwhistle in history of the republic), the ostensible leader of the free world evokes nostalgia for a past that seems to come from an old tv-show lot, with painted backdrops and eccentric old maids walking their cats. The past as the promised land. But it’s a past as the past never ever was, not even for a day. It’s a past created for the specific reason of eradicating the inconvenient present (as all presents are inconvenient).

Metaphorically, apocalypses, in secular or non-secular modes, have often functioned as an inversion of nostalgia. Or is it more accurate to say that nostalgia and apocalypses are corollaries? Maybe. Yes. Nostalgia looks backwards for some Acadian idyll; apocalypses look forward to wholesale destruction and the restoration of the kingdom. In Thomas Cole’s series of five paintings, The Course of Empire (1833-36), a great empire rises and crumbles, victim of moral corruption and environmental depletion. The narrative is simultaneously nostalgic and apocalyptic. It looks forward to the destroyed empire’s return to nature: looking forward in order to look backwards. Now Make America Great Again exploits a similar fabled-past trope, but, despite the Again, without pretense of any type of restoration. The Great Leader replaces old monuments with cold monuments to himself. He builds the world’s ugliest buildings. He orchestrates Nuremberg-style rallies, missing only a willing Leni Riefenstahl to bath him in light. He sports with nihilism, the dismantling of civilization, and could care less about the lessons of the fall of Rome, nor about the long-view compensations of Course of Empire’s return to nature. Even Tump’s nostalgia is a phony, a gyp.

Yet the question still comes to mind, does the old trope still have something to say in times of pandemic, rampant opioid abuse, global protest, collective uncertainty? Even the ancient Christian theologians in their time had gotten a little squishy on apocalyptic thinking: Augustinian eschatology conceded end days were coming, but Augustine himself (354-430) was more or less agnostic about the how or when part. God would take care of the details. Yet, yet, yet— Despite a general trend over the last several millennia in favor of secular humanism and the shucking of old superstitions, the notion of apocalypse still does manage to rattle and excite our post-Original Sin, post-Darwinian, post-Nietzschean, post-Einsteinian imaginations. In times of social distress, we can sense ourselves as kindred to ancient Judaeans, Augustinian Christians and seventeenth-century puritans, seeking agency in a world beyond our knowing. Before the end of the Second World War everyday use of the word apocalypse had been in steep decline, and had almost fallen into disuse altogether. But since 1945 its everyday usage has gone up almost a hundred percent. As a word, as a metaphor, it acknowledges our growing sense that our worst nightmares might not be nightmares. Burning rain forests, police shooting of unarmed African Americans, the coronavirus dead processed in body bags, resource depletion, the holocaust, the advent of the atomic bomb, with its revelatory graphic of skies lit up in flames, aren’t figments. Perhaps, repurposed for 2020, the metaphor is perfect expression for our dread of imminent annihilation, both our own and that of the planet we thought was guaranteed us. Given such outrages, can the kingdom ever be restored?

You might be interested in

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

John Murrell, prolific bandit on the old antebellum Natchez Trace, had a talent for masquerade.

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

The Klan in my backyard.

Childhood is the entertainment of the improbability of an ending, plus an ongoing instability of the moment. When I was a boy growing up in Sudbury, Massachusetts, at five, six, seven, I believed, probably like lots of kids that age, in the commonplace of the miraculous, the likelihood of coincidence, the inevitability of imaginative truth. That’s to say, if I composed a letter from an ostensible pirate in blood-mimicking red ink, complete with treasure map, such a pirate must indeed have existed, swashbuckling through my backyard in some distant epoch. If a time machine could be conjured out of twigs and old cereal boxes, I was, voila, transported to some Civil War battlefield, or reassuringly tragic Viking langskip. A bliss of free association prevailed.

In this once-agricultural now suburbanized colony of Boston, childhood was good. Or anyway, on the little side street we lived on there wasn’t a lot of cultural data to agitate for a conflicting perspective. It was the Sixties in high season, and the anti-war protests, the Freedom Summer, the blown-up churches, the dead kids, the assassinations, Woodstock were in full bloom, yet the Sixties as historical moment occupied only the extreme periphery of my childhood attention, and, as far as I could tell, the attention of the adults around me. Only glimpses of Time magazine pictures of Martin Luther King, My Lai, or the novel wardrobe choice of a formerly orthodox mother, hinted at the world at large. We were—the Cards, our Eddy Street neighbors, the neighborhood kids—safely, homogeneously, white, mainly anglo, aspirantly middle-class. To the kids of young parents—my peers—the draft was hypothetical. The violence gutting the American South might as well have been taking place in Timbuktu. Woodstock—it was something a friend’s uncle had come back from with a different girl than he’d gone with.

Neither did history make much of a dent. A decade or so after the Second World War, in a second spasm of Levittown-like development, the cheap uniformly neocolonial houses of Eddy Street had been thrown up on the site of a plowed-over farm and apple orchard. A busy thoroughfare—Landham Road—connected Sudbury to Saxonville, a rather desultory collection of brick mill buildings that had seen better days. But the traffic effectively cut us off from the wider world. Eddy Street denizens seemed to be claimants of an obscure, freshly buried and irrelevant past, isolated like an Amazonian tribe that has lived for hundreds of years next to another but never known of its existence. The blissful backyard lawns, having been bulldozed of trees, blended seamlessly into a singularly blissfully unbroken suburban desert as far as you could see.

Oddly, such an a-historicized landscape also managed to yield more than its share of precious semi-historical artifacts. Over the years I stumbled across oxen yokes, a Conestoga wagon wreck, hulks of old cars in the scant surviving woods behind our house. Incidentally, our yard also contained a geological oddity that seemed part of an even more ancient past: a hundred yards back from our house, where the Eddy Street development had been stopped at the town border, was a natural amphitheater, banked with high steep slopes, and enclosing a small flat patch of land. The grove we called it. Sometimes we boys flung ourselves from the grove’s sloping banks, seeking, one reckons, a token of desire to exist out of bounds.

One day we heard on the radio—there was always a radio in those days—that a prisoner had escaped from a nearby prison and possibly been spotted in our neighborhood. We kids were all told to stay indoors. Hoping to get a glimpse of him—a guy I imagined wearing a striped uniform who’d be sufficiently menacing to make looking worth the risk—I peered out between a gap in the dining room curtains. Maybe I even opened the side door and stepped out of the porch, electricity jolting my nerves. Who knows?

Eventually, I suppose, he must have been apprehended without a shootout or a chase. I didn’t hear anything on the radio anyway, or from my parents, or if I did hear about the moment it didn’t register with enough jolt for me to remember it now. In any case I never got to set eyes on the guy. The narrative was a bust.

Summers passed. We kids (even our names spoke of a certain freebooting exuberance: Chuckie, Dean, Bib, Dickie…) roved the neighborhood unimpeded by phantom escaped prisoners. We made up our own games and dramas with an assumed proprietorship—in ragtag parades, clothed in garb of Korean war veteran fathers, or in paper bags that we drew on to make up our madcap finery. We were knights, soldiers, and rightful claimants to Eddy Street’s obscurer precincts. One summer we formed a regiment to give battle to regiments from nearby houses. We patrolled Eddy Street on our bicycles (my Schwinn Lemon Peeler, modified with a glowing skull figurehead, being the pinnacle of chopper aesthetic), and swung gigantic tree branches at one another until we collapsed, our bodies depleted. Untethered from adult oversight, we were free agents, feral roving bands.

Let’s just say it. There’s something almost invigorating, almost subversive, about homogeneity of enterprise. I don’t mean this in a nativist/ignorance of outside influence way. I mean it, perhaps, in a knowing of the self as an infinitely variable commodity way, and locating that self in a culture that bolsters it, even in the short term. Of course, culture’s malleable, unruly, unreliable. Of course. One’s place in any culture conditional. But, looking back, it seemed for a moment that for all its blandish pleasures my brief Eddy Street tenure had come at a particularly harmonious time and place, and that its effects were longer lasting than I could have ever anticipated.

But what really prompted the writing of this little essay wasn’t directly related to my childhood at all. It’s something that happened in the neighborhood almost forty years before I was born, and was relayed to me decades after I lived there.

On a warm summer evening in the late summer of 1925, a group of local men, and more than a few from nearby towns—possibly two hundred in all, two-fifty—gathered at a farmhouse on the property my family would own some forty years later. In my imagining, there’s a fine mottled sky, fireflies, clouds, an ambient buzz of mosquitoes, Model T’s looking for parking. The cops were out, state as well as local. The owner of the property, a Spanish-American War veteran and farmer, F W (Perley) Libbey, is a figure obscurely infamous, mostly lost in history’s churning. But one can picture him, as I do, middle-aged, lean with hard labor of farming, suspicious of anyone outside his orbit in way that seems perfectly contemporary. On the night of the gathering, he’s rushing about, making sure cars don’t park in the fields, glad-handing guests, chuckling with the cops and locals about the more-than-expected turn-out, and the possibility of trouble.

Libbey was no innocent, no dupe. A few weeks earlier, he’d been arrested for wielding an unregistered gun at a KKK rally in Westwood, Massachusetts. Klan rallies had been held at his farm earlier that summer, threats made to Catholics, Jews, newly arrived eastern European immigrants. He was up to his ears in vindictiveness. On the night of the rally in what was to be my backyard—probably the grove, bound by the slopes I loved to tumble down—men in the vestments of the KKK were waving placards, flags, burning crosses, their chanting the unregenerate gibberish of those assured of their righteousness.

By six o’clock, the Model T’s, Nash coupes, Durant sedans, were lined all up and down Landham Road (the busy road that we kids would one day be forbidden to cross), it was nearly impossible to get through the phalanx. Latecomers were getting out, walking half a mile. They carried an assortment of clubs, shotguns, pistols, American flags, placards, as if readying for patriotic display. Some came wearing overalls, or suits and neckties of the era, stubs of ties slapping over bellies. Many—most—were wearing white robes, hoods pulled off to let the heat out, and in the mellowing light you could see their faces, reddened, their mouths slackly breathing moist unmoving air.

New group members looked around, seeing where they fit in. Greetings were extended— crushing handshakes. How could they help. Indoors, two or three women cooked pies in a coal oven. All these men were going to be hungry. The lull was proving itself to be comfortable. A few protestors, the Irish, the Italians from Saxonville, where flourishing carpet-weaving mills attracted low-wage workers, were hanging around by the asparagus patch, but not like it was in Westwood.

Pop culture between-wars pre-Depression America came on as modern, uptown, flapper- in-the fountain, jazz-mad pastiche, boardwalk beauty contests, T J Eckleburg, Harlem…. But pockets—nay, great swaths—of America lighted their houses with kerosene (the Libbey farmhouse could have been one), got its news from Readers Digest, and workaday life might seem hardly different from life under, say, the administration of Martin Van Buren. Boys had tramped off to war on the Continent in 1917, presumably returning with visions of Parisian footlights as well as the trenches, but there’s endemically stubborn provinciality in American life—a nasty flip side of our myth- aspiring individualism. Did a couple weeks leave in Paris matter when you returned to the homestead and had to start digging ditches, and an Irishman or Armenian had moved in next door? Even during the War, when black soldiers (in segregated regiments) beat back the Germans in the Argonne Forest, provinciality at home never stopped flirting with terrorizing racism. D W Griffith’s bogus epic of a film, Birth of a Nation (1915), idolized the original Klan, and soon after its release a resurgent second-wave Klan expanded the mission with an anti-Catholic, anti-Jew, anti-Italian, anti-pretty-much- everything-not-born-on-the-Mayflower agenda. All over the South, Midwest, Northeast, the new Klan stepped up its intimidation efforts, like a boosterish Kiwanis club with race war on its mind.

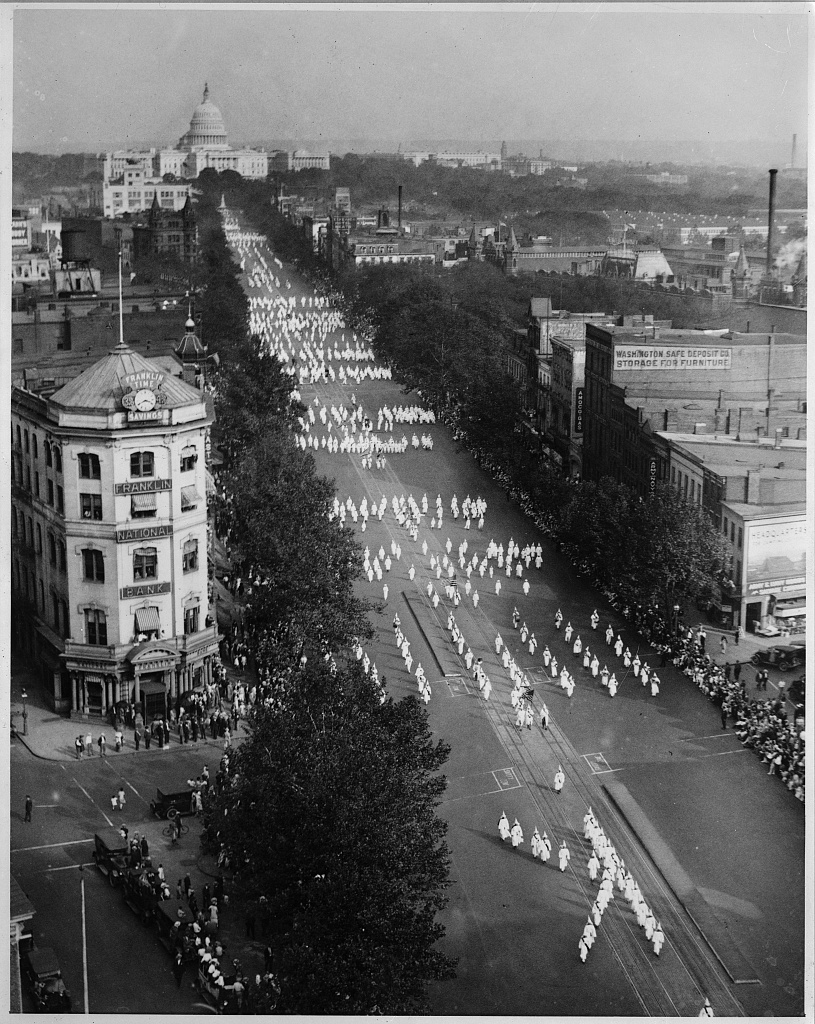

One only has to follow the segregationist folly of Know-Nothingism to Jim Crow to the Immigration Act (1924) to get a pretty clear picture: the Klan was just a silly costumed manifestation. The original Klan had topped out at a hundred thousand or so members, mostly ex- Confederate freelancers trying to fend off Reconstruction and hold onto a slippery white hegemony. But by 1925—the peak of the second Klan’s cultural saturation—the Klan could muster, nationally, some four million members, give or take a few million. In Massachusetts alone there were estimated to be 80,000 hooded costumes ($6.50 each) hanging in the backs of closets of farmers, merchants, ministers, police captains, bankers, undertakers, teamsters, shop clerks.

Nineteen-twenty-five may have been a pretty slow year for lynching—only seventeen African Americans were tortured, hanged, mutilated—but just a few days before the events at Libbey farm, some 40,000 Klansmen paraded through the streets of Washington DC, singing, jabbing the air with their signs, marching in formations of crosses and the letter K, demonstrating the Klan’s power in the very heart of the democratic experiment. And it was in this superheated atmosphere that immigrants, mostly first generation, some Irish, Italians, came ambling over the hill from Saxonville, down dirt-paved Landham Road, confronting the armed and riled-up Klan at the Libbey farm.

It’s impossible to piece together exactly how things started, but maybe not hard to piece together how it accelerated. Feeling an advantage in numbers, protestors pressed on the farmhouse, barn and chicken coop; Klan members, feeling cagy, telephoned for reinforcements and got through to some guys getting off the shoe factory late shift, maybe an accountant or who’d already turned in for the night. In the next hour or so, additional men—twenty, thirty—were coming down Landham Road from the north, beating their way through the protestors. By this time it must have been 11:30, 11:45.

Names were called, let’s say. Papist. Shit-for-brains. Stronzo. Someone bent down to pick up a rock. Someone hurled a piece of an oxen shoe. A Klansman was hit in the shoulder. On the side of the head… a broken nose gushed blood and snot. The cops were doing their best, but they’re they’re human, they’re not trained for this. A furniture store clerk—maybe he’s a kid, twenty-three—waved a rifle out the chicken coop window.

Everyone around him started clamoring, taunting, then you can’t do anything but shoot, can you. Maybe he doesn’t even remember after a while. One of the Irish spun around, crimson pooling in his shirt. It was on his face, blood everywhere. The guy was just standing there, like he forgot something at the store. Now other guys started firing into the crowd, and protestors, trampling over each other to get out of range, were shouting, sobbing, cursing, lobbing back rocks.

Five protestors were left behind, binding their wounds with their fingers, licking blood. William Bradley. Frank Maguire. Edmund Purcell. Thomas Sliney. Hit with buckshot. 22. Also Alonzo Foley. The guy who hadn’t moved. Alonzo crumbled to his knees now, holding his head with a cocky grin, his eyes fluttering. Twitching. A priest, youngish, soft-handed, his hair tight to the scalp, murmured last rites, giving the sign of the cross. After a while the others got taken off in Saxonville taxis, to a doctor presumably sympathetic. Alonzo went in the back of a four door sedan. Now it was probably around one o’clock in the morning. Maybe later. Kids hanging on the edge of Landham, losing interest. Dogs pacing up and down. State Police, motorcycle cops spread out over the asparagus fields, the orchard, and chicken coup, rounding up Klan guys, Sudbury guys— Curley Libby, Robert Atkinson, Ralph Chamberlain, Oliver E. Ames, Harry Rice—some of whose names are on municipal buildings these days. Guys from Waltham, Needham, Newton, Wellesley. The son of the police chief got scooped up. Light was starting up over the trees, ragged, unconvinced. Nash roadsters, Model T’s paused, trying to get through, the drivers squinting through smudged spectacles on their way to work. A couple half-eaten pies were strewn across the farmhouse kitchen floor, the Klan women raking up the mess with forks and dustpan. Alonzo was supposed to die in the middle of Landham Road, buckshot to his temple. But the fact is he didn’t. He lived until well after my family and I moved away. In 1979, at age 87, Alonzo died. I was on to other things by then, pursuing my own academic and literary aspirations, leaving Eddy Street far behind, I hoped.

Nineteen-twenty-five had proved to be the high water mark for this version of the Klan. The march on DC was the largest assembly it would ever muster. By the 30s, wracked by scandals, internal corruption, and external resistance to its vision of a racially, morally unanimous America, the Klan shrank to a few thousand members, persisting only in isolated chapters throughout the country. The respectable attorneys, bakers, mechanics, farmers, returned to harboring their grievances in less civically boosterish ways, or modified them in accommodation of a world that wouldn’t cooperate with their mania for purity. By the time my parents purchased their Eddy Street plot, I could live in relative obliviousness of the events of forty years earlier, free to cruise on the Lemon Peeler over land where old Libbey had meant to make his stand. Only, like some virulent strain of bacteria, the Klan did reconstitute itself in the civil rights crisis of the late sixties, at the time Libbey himself had gone to his grave (1965). A virtual protectorate of the intrenched Southern political power structure, it renewed its commitment to subjugation through night-riding vigilantism, murder, terrorism.

America tilts to the affirming word, the frisson of possibility, a kid riding a bike. But it’s reminding you. Always.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual