Sojourning down American highways via thumb.

Imarvel now that I was able to get from my apartment door in Brooklyn to Pennsylvania or Maryland or West Virginia and back in one long weekend without spending a dime. In those days, if you were so inclined and willing to put up with a little discomfort—standing on a treeless road a couple hours, camping by a culvert—you could make it across the entire continent for the price of a couple sandwiches.

Being of an abstracted and pilgriming nature, I was inclined.

I started hitchhiking in college as a means of getting from one place to another for free, and picked up on it relatively quickly. Via hitchhiking, the journey between Amherst, Massachusetts, where I was going to school at the University of Massachusetts, and my parents’ house in suburban Boston, was about an hour and a half if you were having any luck, three or four otherwise. By nature, I was as inclined to wander the byways of the country by sticking out my thumb as I’d been inclined to explore neighboring streets and towns via bicycle as a child. Summers in college, I’d catch rides to a beach town on Cape Cod where a tantalizingly intemperate girlfriend was living, and provided more than ample stimulus to travel to her via any means available. These early hitchhiking forays were primarily utilitarian, insofar as I wanted see my girlfriend, but they advanced certain metaphysical aspirations. It’s an exaggeration to say that hitchhiking made me a writer, any more (or less) than the intemperate girlfriend did, but some evenings, standing by the side of a road as light drained from concrete skies, displaced by quavering halos of streetlamps, I grew accustomed to a certain solitary perspective and depended on a wandering mind to preserve a toehold on reality that may have fueled literary inclinations.

Hitchhiking provokes hallucinations: mirages, a sense of temporal fluidity, hovering in margins. If you’ve ever been stuck in a unknown town, transportationless, you’ll know what I mean. One realizes one belongs, metaphysically, only by provision. I remember once, after hitchhiking back from the Cape, walking down the street where my parents lived—about 3:30 in the morning, I guess: an indeterminate time of errant lovers, nightshift workers, long-distance commuters pulling out of driveways—and the doorbell buttons of three or four houses were glowing identically yellow, as if floating in a medium of clear jelly. It was an image that, for all its banality, made my throat clench. I remember staring, transfixed. Even here, on the overfamiliar street of my childhood, there was a quick thrill of exile that held me in thrall.

Historically speaking, it may be no accident that hitchhiking started in America. Maybe it’s our gift to civilization, along with jazz or superheroes. The notion that you could or ought to submit your fate to the goodwill of strangers harkens, perhaps, historically speaking, to a quainter version of American life. Let’s pick the nineteenth century, for sake of discussion. 1829’s a good year—with its mania for macadam road and canal building. The Erie Canal is nearly complete. Andrew Jackson sits in the Executive Mansion, promoting internal improvements. But railroads have yet to proliferate. To get from Utica to Albany, you can hop a flatboat, and find yourself there in ten hours. In Mississippi, a wayfarer dropped at a levy landing might start hiking with his satchel, and in the afternoon knock on a stranger’s door—the expectation being he could get a cot for the night, a rude breakfast in the morning. Perhaps the wayfarer offers some sort of payment, or the host holds out his hand for it. Or not. But such was the temporary, transactional, improvisational nature of these early alliances. Doubtless transactions could be fraught, strangers turned away, robbed of their possessions. Bands of highwaymen did, after all, prey on peddlers and travelers along the Natchez Trace between Nashville and Natchez…. But travelers, in general, depended upon predictable outcomes, and acted in accordance with this premise. Highwaymen be damned.

A couple decades later, traveling in the deep south before he became a landscape architect, and reporting for the New York Times on the lore and folkways of what amounted to a foreign people, Frederick Law Olmsted complained of the mean hospitality offered by supposedly hospitable Southerners. “We slept in all our clothes, including overcoats, hats and boots, and covered entirely with blankets,” he grumbled, “and after going through with the fry, coffee and pone again, and paying one dollar each for the entertainment of ourselves and our horses, we continued our journey.” Sleeping in stage stops, haylofts, spare cots, crossing rivers on private ferries, Olmsted relied on informal linkages, improvisation. But his complaints about poor blankets and pone strike me as slightly ungrateful, as if a hitchhiker were to gripe that every car that passed didn’t pick him up, or a driver in one that did might not tell fascinating stories. Imagine knocking on a stranger’s door in 2018, looking for a cot and a meal. In 1857, no backwoods farmer was under obligation to take in a probably pretty disheveled Yankee, but even in the backwards antebellum South, a wayfaring stranger (a white stranger…) wouldn’t go bedless or unfed for the night.

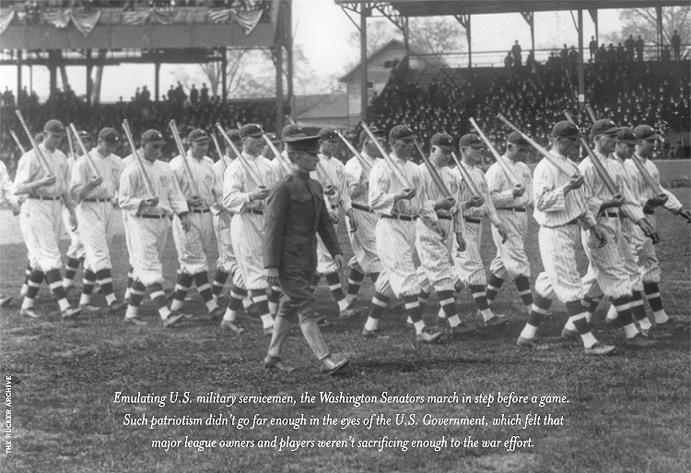

In 1900, about 8000 cars were registered in the US. Twelve years later there were 901,596, and the American troubadour poet, Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, could write: “When the weather is good, touring automobiles whiz past…. About five o’clock in the evening some man making a local trip is apt to come along alone…. He will offer me a ride and spin me along from five to twenty-five miles before supper.” By 1917, when the US entered the Great War, precisely 4,727,468 cars cruised the American roads, and car culture as we understand it today was well underway. By many accounts, hitchhiking (insofar as the term applies specifically to petitioners of automobiles) proliferated around the army training camps around the country. In such population centers—Camp Devens, Fort Slocum and Camp Funston—word spread quickly: doughboys on leave could hitch rides home for the weekend, visit girlfriends far afield, possibilities that must have seemed fantastical to boys who’d never been farther from home than they could travel by horse in a day, as Faulkner said of the young soldiers in the Confederacy. By the time the movie, It Happened One Night, came out in 1934, hitchhiking was common enough that a driver who stopped to pick up Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert recommended it for honeymooners. “If I was young, that’s the way I’d spend my honeymoon. Hitchhiking.”

In my own period of wandering and hitchhiking, I took buses, flew, hopped freight trains, bicycled, crisscrossing the continent from New England to Kansas, Texas, the Yukon, Alaska, the Deep South, not aimlessly, but with no specified agenda in mind other than to take in impressions, see how people lived, and what the places they lived in were like and what their faces were like. Despite my pilgriming nature (maybe that’s not exactly right—), I wasn’t on a quest, but rather, I suppose, I was hoping to experience life in a wide gyre, and live as fully as budget and tolerance for an ascetic existence could sustain. As a kid, I used to share a back seat of a station wagon with my siblings as the family drove across the country (my father was a junior high school principal, and had summers off), and, though I was more likely to read than gander, I suppose I absorbed something of the country’s history and geographical extent by osmosis, taking in clouds over the Rockies, the lullaby of tires on pavement…. Trips forever associated with long highways going I wasn’t sure where.

I’d been warned, of course, of the perils—strangers who’d take your things and leave you on the side of a road. The warnings, coming from parents and others seemed unrelated, for the most part, to experiences I had. There were some unpleasant episodes here and there. Once when I hopped into the cab of a snorting eighteen-wheeler, the driver, a bluff, ruminative man, began to point out the exquisite comfort of wearing women’s underwear on long hauls, and urged me to try the same. He didn’t press himself on me, but cheerily tried to coerce me into changing there in the cab. One night, outside a city in Arizona, a man seemed to mistake me for his son, lamenting the son’s loss (I was unclear what he meant—) while massaging my thigh. In Georgia, I was once left, precisely as warned, at a gas station as the two yahoos I’d been riding with for hours drove away with my backpack, which contained my wallet, clothes, precious books, what amounted to everything I possessed at the time. But these incidents, however sordid and discomforting, were not exemplary. Oftener than not, the driver would belong to the class of middle-aged, mildly disappointed men in thankless marriages, with crap jobs, overextended credit, equipped for survival by the barest skim of self-reliance, but kind enough to pull over for a stranger. They shared, almost universally, stories otherwise backlogged, about affairs, lost sons, sad denouements, secure in the fact that they’d never see me again. Like a descendant of Nick Caraway in Gatsby, I was subjecting myself to the secret griefs of desperate men, but I listened. I honed a talent for listening, sometimes into the night, with the low murmur of a radio for accompaniment, and the hushed attention of the stars.

Hitchhiking must have peaked as an unstigmatized means of getting around sometime in the 60s or 70s, lingering past the Merry Prankster, Haight Ashbury, Woodstock eras, and hanging on into the disco or later. The weekend on-leave excursions of the Great War doughboys layered not altogether clumsily onto the sojourns of hippies and freelance adventurers: doughboys, by way of Vachel Lindsay, updated as free-spirited hippie girls with wind in their hair. But at its peak hitchhiking was already perceived as something subversive and dangerous. In 1968, Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys picked up a couple free-spirited girls, who happened to be Charles Manson followers. Within a few days Manson himself and the girls moved into Dennis’s Malibu house. They were there two months before Dennis finally got creeped out, and kicked the ensemble out. It was no longer just doughboys or hippies or honeymooners or Beat Generation hepcats on the road, but a dangerous element exfoliating Americans’ belief in themselves. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) may be one of the most celebratory, even patriotic novels of the 20th century, but it’s self-consciously premised upon the trope of outsider as patriot (a trope that usually works best if you’re in the in-group). Take a look at photos from the 50s and 60s—it’s mostly not Beat poets and hippies, but the suit-and-tie types scratching their heads at the non-conformists. Despite jazz clubs, the Further Bus, Woodstock, the Stonewall riots, the Beats’ and hippies’ revolutions eventually collapsed under the impossible burden of utopianism, their radicalism shrunken and commodified: the counterculture pressed against the barriers but never really broke through.

The publicity surrounding the Manson murders (a year after Dennis Wilson picked up the girls) may not have spelled the absolute end of hitchhiking, but it was around that time that signs posted on the roadsides warned of dangerous freeloaders, ex-cons, lechers, undesirables. The Interstate system (an Eisenhower-era scheme completed, more or less, thirty years later) institutionalized the prohibition of hitchhikers. By 1986, as the coast-to- coast Interstate (I-80) was completed, there were 126,425,301 cars on the road. Roughly 7.5 for every 10 citizens. Essentially, a state drivers license was a national ID card. Vehicle ownership was tantamount to citizenship.

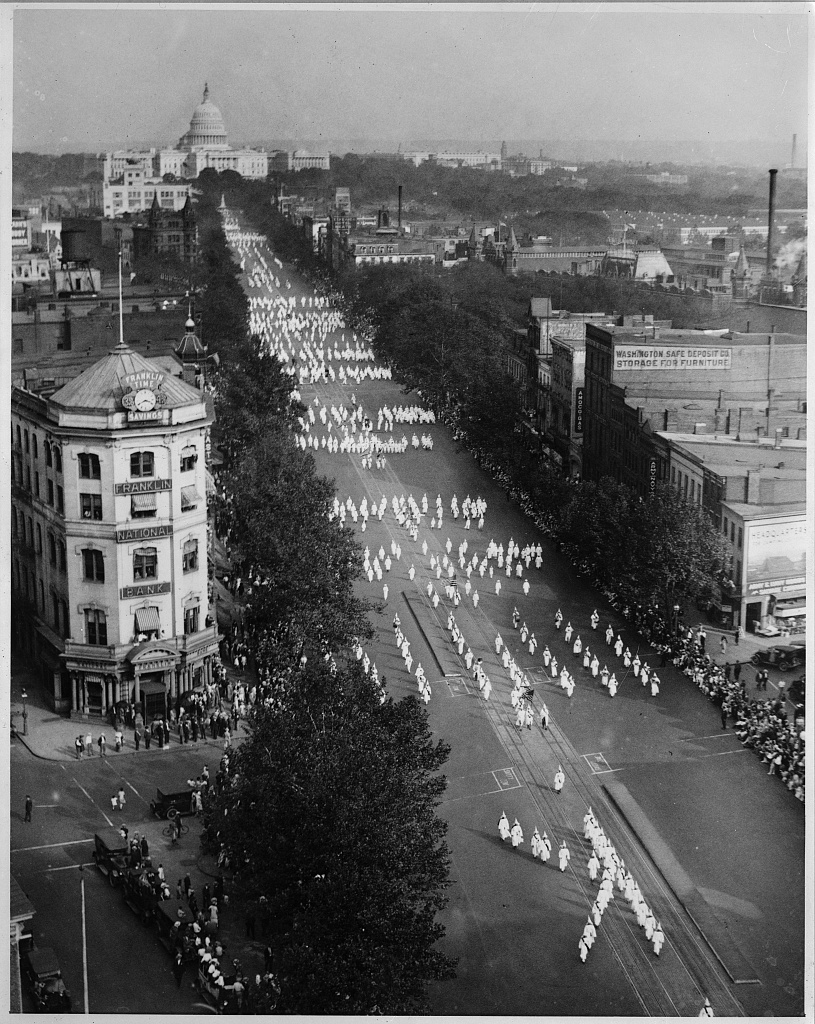

So the comparatively brief ferment of 60s Samaritanism may have proved unscalable, but it also proposed an ongoing interrogation of middle-class American cushiness. It hardly needs saying, but I’ll say it anyway: our national optimism has always had a narcissistic side that claimed America as the Promised Land. The guardians of mainstream culture (self-appointed or otherwise) take it upon themselves to keep out the undesirables (from Catholics, Germans, Chinese in the 19th century, to Jack Kerouac, or Mexican “rapists” at the border). If hitchhikers too were eventually cleared from the road in the name of decency and conformity (a hitchhiker on the side of a road in 2019 is as rare as an Ivory- billed Woodpecker) then it seemed part of a general repudiation of Woodstock-style upheaval. Outwardly, the end of hitchhiking was a small extinction, perhaps, but small extinctions take down ecosystems. Hitchhiking had always been an experiment of democracy, a spontaneous test of our trust in one another, and its demise took with it some of that trust, or the other way around.

One morning, toward the end of my hitchhiking days, I was half-heartedly walking through a hamlet in Missouri, holding out a sign. A car pulled over. I thought a voice called my name—an impossible idea. I didn’t know a soul within a thousand miles of wherever I was. Another hallucination, the product of long stretches of standing beside hectic highways— The driver, dark haired, early twenties, introduced himself. Then asked if I was who he thought I was. What could I say? I looked at him. Nothing computed. Sometimes even simple facts, expressed without adornment, throw you into madness.

Here’s the short version: three years earlier I’d had a conversation with a family at a campground in western Montana, part of a missionary group caravanning to Wasilla, Alaska, up the Alcan Highway. They invited me to visit Wasilla were I ever to make it there. In fact I did—several months later. I had a brief dinner with the group and left the next day, taking the ferry from Haines, on the panhandle, to the Lower 48. Three years later, the person who pulled his car over in Missouri recognized me as the person from the campground and the dinner. He’d been a member of the missionary family, a teenager then. When he saw me, he was sure enough that I was the same guy that he called to me by name. People run into people they know all the time at St Mark’s Basilica, Time’s Square, the footwear collection at the Smithsonian, and call it coincidence. A sceptic might have a point in calling coincidences nothing more than fictions appearing to organize into natural order, making secular religion of nothingness. But this— To encounter this guy on the side of the road in a town in Missouri, population 15,000 (I’m guessing), tends to make one believe in guiding forces, and wonder at the drollness of fate.

I got in, we talked inconclusively for a while, as if we ought to make something of the happenstance but didn’t know how to go about it. I should come for dinner, he said. Meet his wife. Thank you but I was in a rush, I told him not untruthfully; not too far down the road I got out of his car, and shook his hand through the window. It felt both meaningful and very inadequate. What’s there to say on such occasions? We knew each other only as unwitting associates in a singularly unlikely episode; characters in someone else’s narrative. I walked along with my backpack and sign, consciousness of being gobsmacked. A little wind picked up, if I remember, an unremarkable bit of weather that seemed obliged to a particular place, that couldn’t be reproduced in any other. I was on my way to Boston, grad school. I was coming to the end of hitchhiking too.