The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

More

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don’t know.

Apocalypse, noun apoc·a·lypse | \ ə-ˈpä-kə-ˌlips plural: apocalypses

- one of the Jewish and Christian writings of 200 b.c. to a.d. 150 marked by pseudonymity, symbolic imagery, and the expectation of an imminent cosmic cataclysm in which God destroys the ruling powers of evil and raises the righteous to life in a messianic kingdom

- something viewed as a prophetic revelation

- a great disaster

—Merriam-Webster

Naturally, talk of apocalypse is more lively these days than at any time in recent memory. Ends are on everyone’s mind. There are, of course, people who will tell you that such ideas are best left out of enlightened liberal conversation: climate change, racial injustice, political mayhem, unending wars, being human problems with human causes, not something stirred up by a glowering retribution-minded desert god. Yet the conversations keep coming up, and the idea of god as a controlling presence, as an apocalyptic being, literal or metaphoric, is endlessly enticing even in 2020. The twentieth century theologian/ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr, who was always on the lookout for links between verifiable and eternal worlds, put the modern existential implications of the apocalyptic metaphor front and center: The apocalypse, he wrote, “is a mythical expression of the impossible possibility under which all human life stands.” And in some ways, the implications of “mythical expression” in Niebuhr’s framing might be the same for us in the twenty-first century as it was for the early Judaeans who first conceived of apocalyptic imagery: we stare into the cosmos with awe and trembling. Niebuhr’s winking, “impossible possibility,” points to a crossover of hopelessness and hope, the daily duality of the human condition. Life now, as ever, hangs in the balance.

Historically speaking, there have been plenty of apocalypses to go around. For three millennia, give or take, the apocalypse idea drifted in and out of favor, a readily mutable and spiritually resilient shorthand for temporal anxiety, an enduring myth by which existence might somehow be understood as transcending bodily constraints. The franchise, as Niebuhr hints, has always traded in all kinds of dualities: hope and despair, possible and impossible, end and beginning, salvation or damnation, annihilation and rebirth, submission and domination, reality and myth. We sift through these in hopes of finding a mythology apposite to our times. And as apocalypse metaphor de jour, the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is unsettling to us not just because of the havoc it wrecks in our streets, homes, workplaces, performance spaces, schools, stores and old folks homes, but because of its disruption of the habits and social customs that have often offered fellow feeling in other would-be apocalypses. Metaphorically, coronavirus, like the 1918 flu before it, ramifies into a diabolical test of social solidarity. In midst of other catastrophes that have tested our forbearance—in wars, pestilence, genocides, to name a few—physical touch, the glances of strangers on the street, offer countervailing human connection. But coronavirus exaggerates havoc, robbing those who are not felled by it of handshakes, kissing, hugs, the bodily frisson and common cause of everyday life, turning friends and lovers into risk factors, and strangers into vectors of the apocalypse. A few months ago a dear friend’s father, whom she used to visit weekly in a nursing home dementia unit, was diagnosed one day and died the next, and the sight of my friend, virtually alone in a blustery Massachusetts cemetery, her fingertips touching the closed box in the back of the hearse that held her father, was one of the most wrenching sights I’ve seen in my lifetime. Two attendees besides the funeral director at the burial. Our aloneness laid bare, bare—

It was a scene that begged an artist to find small redemption in its humbling dignity. At other times when our purchase on life has suddenly become precarious—during the Black Death, the 1918 flu, the holocaust, the AIDS crisis, say—artists have sought to offer metaphors, a way of shaping our collective understanding of the virulently incomprehensible. In the late Middle Ages, as Black Death swept across Europe and Asia, apocalyptic iconography adorned pulpits, illustrated manuscripts, mosaics and the like. In the pandemic’s earliest stages, the imagery tended toward the punitive, pestilence as an instrument of god’s clearinghouse. Anonymous sinners were cast into fiery pits, decomposing bodies set upon by jowl-licking dogs. Only toward the later stages, with millions already dead (many of whom may have been assumed to be non-sinners) did the imagery become a little more sympathetic, the sufferers and suffering humanized, and the artists’ less obsessed with sending earthly sufferers off to eternal suffering in the afterlife. On the literary front, one of the most well-known books to come out of this period reconsidered the Black Death as an instrument of suffering but also pointed toward human commiseration as counter to human impotence. In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353), a group of young people on the run from the plague entertain each other in a country villa, telling tales that are alternately erotic, heroic and comic. Even in the super-saturatedly religious time, steeped in crippling apocalyptic mythology, the young protagonists sought to create a rich secular life outside familiar tropes of salvation or damnation, with hesitant ambivalence about the origins of “the death dealing pestilence, which, through the operations of heavenly bodies or of our own iniquitous dealings, [was] sent down upon mankind for our correction by the just wrath of God.…”

In our own times, global pandemics, widespread environmental catastrophe, mass unemployment, the shared psychic evisceration of 9/11, neverending racial injustice, a crisis of identity in an increasingly dystopian American scene, has introduced a psychic trauma that seems not far from that of Boccaccio’s protagonists. As a rule, we might feel detached from millennia-old religious beliefs, but as we look into the crystal ball of our collective future we see little reason to believe our terrestrial kingdom can be sustained, and grapple with more than metaphors of mass death. In certain circles, casual conversation turns, almost invariably, to end days, destruction of existing mores, a society facing mortal danger from a virus that invisibly taints the air we breathe, and, in this country, the political party of Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt and Eisenhower being held in thrall to a thuggish simpleton. A redo seems not only just, but gives hope of a future when saner gods might reign.

In the Seth Rogan buddy-cum-end-of-the-world comedy, This is the End (2013), the end in question comes at a party at James Franco’s house as Hollywood partygoers tumble into fiery pits or are sucked up in blue columns that seem to operate like pneumatic tubes used in nineteenth century department stores, leaving Seth, Franco and their buddies behind, self-quarantined in Franco’s modern Xanadu. Modernists with vague religious awareness, for the life of them they can’t quite put together a list of the deadly sins to sort out why they’ve been left behind, and like seventeenth century theologians debate the Holy Trinity and power of god, when Seth suddenly has a stoner epiphany: “I mean it’s like, its like the real apocalypse. It’s like the Book of Revelations. That means there’s a god, right? That there’s a god? I live my life as if there’s a god, but.… Who actually saw that coming—that there’s a god?”

End came out early in Barack Obama’s second term, before the advent of MeToo, but months after the murder of Trayvon Martin, at a time when cynicism and possibility seemed to be struggling for dominion at the edges of America’s ailing frontier. Seen from a much darker 2020, the lesson of End feels quaintly hopeful, decidedly non-Old Testament, non-Trumpian. Care for each other. Don’t be a douche. Maybe there’s a god. Having learned their lesson, the buddies ascend in the blue columns to a dance-party heaven that’s everything a man-child could wish for, certainly not a place, seven years after the movie came out, most of us would consider congruous to our age of racial reckoning and world pandemic, where we’re inclined to regard each other like stunned survivors.

What exactly is an apocalypse anyway? And, by the way, who gets to advance to the next level? As an idea it’s harder to pin down than Webster’s might let on, or we might think of it. The word, Greek in origin (ἀποκάλυψις, apokaluptein), literally means “uncover,” or “revelation,” and the promise of a new beginning. God would flush out an old fallen world and replace it with a new, improved version. Such thinking really started catching on around the time of the Babylonian exile (597 BC – 538 BCE) as captive Judaeans were deported to Babylon. Judaeans had good reason to wonder about god’s promise that their kingdom would last forever. How were they supposed to take god at his word when their kingdom was plundered, their citizens taken away in bonds? An explanation was needed. So if the apocalypse idea came out of what was essentially a contract dispute, and after several millennia of additional contract disputes, one might argue it now accounts for tent revivals, cosmology, dystopian novels, Decameron, reform movements, This is the End, and nowadays what feels like collective anxiety in the declining days of the American moment.

On a secular level—not just god’s—apocalypses have also been political, and known to operate as displays of power, separating deserving from the undeserving. Take America in 2020. Over the course of his White House lease the ostensible leader of the free world has been barely able to maintain a baseline imbecility. By any objective measure he’ll go down as the worst president in history. But—and here is the crux of god’s methods too— the strongman tactics Trump employs with such gloating glee create a state of perpetual terror about our collective hold on the world. This is the End could laugh at it, but here we are— At the instant of pandemic, and collective national self-examination on questions of race and gender equality, the ostensible leader of the free world wades through cleared streets like a third grade bully, incapable of even pantomiming facial expressions beyond scorn and self-congratulation. An apocalypse suits his agenda of wholesale moral and physical destruction. By “making America great again” (that “again” being, perhaps, the most potently loathsome dogwhistle in history of the republic), the ostensible leader of the free world evokes nostalgia for a past that seems to come from an old tv-show lot, with painted backdrops and eccentric old maids walking their cats. The past as the promised land. But it’s a past as the past never ever was, not even for a day. It’s a past created for the specific reason of eradicating the inconvenient present (as all presents are inconvenient).

Metaphorically, apocalypses, in secular or non-secular modes, have often functioned as an inversion of nostalgia. Or is it more accurate to say that nostalgia and apocalypses are corollaries? Maybe. Yes. Nostalgia looks backwards for some Acadian idyll; apocalypses look forward to wholesale destruction and the restoration of the kingdom. In Thomas Cole’s series of five paintings, The Course of Empire (1833-36), a great empire rises and crumbles, victim of moral corruption and environmental depletion. The narrative is simultaneously nostalgic and apocalyptic. It looks forward to the destroyed empire’s return to nature: looking forward in order to look backwards. Now Make America Great Again exploits a similar fabled-past trope, but, despite the Again, without pretense of any type of restoration. The Great Leader replaces old monuments with cold monuments to himself. He builds the world’s ugliest buildings. He orchestrates Nuremberg-style rallies, missing only a willing Leni Riefenstahl to bath him in light. He sports with nihilism, the dismantling of civilization, and could care less about the lessons of the fall of Rome, nor about the long-view compensations of Course of Empire’s return to nature. Even Tump’s nostalgia is a phony, a gyp.

Yet the question still comes to mind, does the old trope still have something to say in times of pandemic, rampant opioid abuse, global protest, collective uncertainty? Even the ancient Christian theologians in their time had gotten a little squishy on apocalyptic thinking: Augustinian eschatology conceded end days were coming, but Augustine himself (354-430) was more or less agnostic about the how or when part. God would take care of the details. Yet, yet, yet— Despite a general trend over the last several millennia in favor of secular humanism and the shucking of old superstitions, the notion of apocalypse still does manage to rattle and excite our post-Original Sin, post-Darwinian, post-Nietzschean, post-Einsteinian imaginations. In times of social distress, we can sense ourselves as kindred to ancient Judaeans, Augustinian Christians and seventeenth-century puritans, seeking agency in a world beyond our knowing. Before the end of the Second World War everyday use of the word apocalypse had been in steep decline, and had almost fallen into disuse altogether. But since 1945 its everyday usage has gone up almost a hundred percent. As a word, as a metaphor, it acknowledges our growing sense that our worst nightmares might not be nightmares. Burning rain forests, police shooting of unarmed African Americans, the coronavirus dead processed in body bags, resource depletion, the holocaust, the advent of the atomic bomb, with its revelatory graphic of skies lit up in flames, aren’t figments. Perhaps, repurposed for 2020, the metaphor is perfect expression for our dread of imminent annihilation, both our own and that of the planet we thought was guaranteed us. Given such outrages, can the kingdom ever be restored?

You might be interested in

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

John Murrell, prolific bandit on the old antebellum Natchez Trace, had a talent for masquerade.

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

And you whose face so famously winces

from its inner self, ghost trace of pockmarks

of some earlier you, lips agape, like a corpse’s,

you—you of no fixed address, no idée fixe,

gifted in fetish of doubting and double regret,

you must set loose from this abandoned shore,

perchance to trip upon another more

unyielding. This milieu, this passing second,

this whirling wheel collapsed in tungsten light,

is Rome as Athens was to the Romans.

One wanderer seeks matter in the havoc

of his wandering, as you seek substance

in the doubting self, confiding to interrogative you,

hedging thoughts as if they might portend mortality.

You might be interested in

Charles Manson and his followers settled in at the Spahn Ranch, in Los Angeles County, in the summer of 1968.

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

It was a time of nicknames.

In the decades following her trial for the murder of her father and step-mother, Lizzie Borden walked the streets of

A brief look at the untold riches of cocktail literature.

When Prohibition in America ended on Tuesday, December 5, 1933, at precisely 4:31 pm, almost overnight the drinking public decamped from backrooms and speakeasies into suddenly plentiful public taverns and opulent supper clubs. After thirteen years of being relegated to bathtub gin concoctions, the cocktail was poised to reestablish its former glory.

At the same time, liquor-related literature started making its own comeback. Liquor had always been a staple literary subject. More than 25 liquor-related titles had been published during the cocktail’s first Golden Age, between the mid 1800s and Prohibition. The first of these, The Bon Vivants Companion-or-How To Mix Drinks, by Professor Jerry Thomas appeared in 1862, the last, Hugo R. Ensslin’s Recipes For Mixed Drinks, in 1917.

During Prohibition, drink manuals came mostly from Europe, such as Harry Craddock’s epic Savoy Cocktail Book (1930), featuring recipes from London’s Savoy Hotel bar, and Harry McElhone’s mischievous Barflies and Cocktails (1927), which showcased drinks, anecdotes and cartoons from the legendary Harry’s New York Bar, birthplace of the Sidecar, Bloody Mary, Boulevardier, French 75 and more (in continuous operation since 1911, by the way). The few books published in the U.S. consisted, naturally, of manuals on how to circumvent the law and make your own booze.

But by 1933, a new wave of cocktail books started showing up on bookstore shelves; between 1933-1935 more of these books were published than during the entire first Golden Age. For the most part, they were written by talented bar owners and tenders. But one of my favorites, So Red The Nose-or-Breath In The Afternoon (Farrah & Rinehart, 1935), features thirty libations presumably concocted and presumably enjoyed by the likes by Ernest Hemingway (of course!), Theodore Dreiser, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Irving Stone, Alexander Woollcott, Erskine Caldwell.

So Red is a time capsule, evocatively illustrated by Roy C. Nelson, whose drawings, done in the post-deco style of Al Hirschfeld, or 30s and 40s Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies cartoons, conjure a time when the past was not so far in the past. Its recipes also tended to run to the gloriously, celebratorily, absurd. Hemingway’s Death In The Afternoon Cocktail comes across as a wtf! joke of a drink –

Pour 1 jigger of Absinth into a champagne glass. Add iced champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink 3 to 5 of these slowly.

But in fact this is a rather legendary Hemingway recipe that’s been on menus since the cocktail revival went into full swing circa 2005.

Is this drink, essentially an Absinthe Highball, any good? Well, if bitter wormwood/anise laced sparkling wine ignites your senses, then by all means, drink three or five. Personally, I enjoy absinthe, especially when it’s ritualistically served by dripping water though a sugar cube that’s been placed on a perforated absinthe spoon.

Dreiser’s American Tragedy Cocktail includes these special ingredients:

1 teaspoon full nitroglycerin

1 treaspoon heavy ground gunpowder

2 jiggers ethel gasoline

1 lighted match

Please accompany the above by horrific series of eccentricities, aversions and drinking habits based upon my notorious and incurable alcoholism. Limit one drink per customer, please, notes Dreiser.

And the Dry Martini pops up again in Kenneth Robert’s Lively Lady:

take a small pitcher with a well rounded interior put in it nine cubes of ice

add four cocktail glasses of gin

add two cocktail glasses of niolly prat vermouth

stir briskly sixty revolutions with a long-handed spoon (the only method which doesn’t bruise the gin)

pour into cocktail glasses

add twist of lemon peel so lemon oil is sprayed on the liquid

repeat until pitcher is empty

Hmm. That’s how I’ve always made my Martinis, although I add a dash of orange bitters, as called for in the original recipes circa 1903-1906. (Note: in old cocktail books, a cocktail or wine glass equals two ounces; a pony is one ounce)

These days writers, perhaps, don’t drink as public performance art half as much as they did eight decades ago. In 2020, we’re more apt to hear about the sobriety of ex-drinkers like James Ellroy and Stephen King than the epic bouts and hangovers of Cheever, Bukowski, Mailer et al. But if So Red ushered the way toward excesses, it also foretold the craft cocktail revival of early twenty-first century.

Speaking of snapshots of time, my copy has an interesting handwritten inscription on the inside cover that I’ll share with you here. I have to translate the cursive Palmer Method, so here goes:

December 25, 1940

Dear Bob,

I pray that this volume will take its place with the rest of the valued works you prize so highly.

This is by no mere collection of story tellers nor anthologies of verse, but a practicable, workable affair used by those of modern epicurean tastes.

I pray for you, brother.

Rev. Jay

Brother Cleve has traveled the globe, playing keyboards and spinning records. Fascinated by local spirits, he’s collected innumerable books about cocktails and spirits. He is the Beverage Director at Paris Creperie in Boston, MA, and lectures extensively on cocktails and their histories.

Turn it up. When rock’n’ roll was punk, and the search for meaning in the mosh pit.

As the recognizable form, rock’n’roll came from out of seemingly nowhere and seemingly everywhere, organic but commercially driven, inevitable and accidental, it derived from prison hollers, English and Scottish ballad singing, Brill building song sellers, the invention of the transistor, the Arkansas hoedowns, shoeshine singers, Louisiana radio shows, West African gourd instruments, the chitlin circuit, the slave spirituals, medicine shows, minstrel shows, Mississippi riverboat dance band shows, zippos, sheet music emporiums, teenage grooming, backseats of cars, the speakeasy and cathouse stride players, homemade guitars, Yiddish theater, vaudeville and barbershop quartets and Camptown Races Do-da, and in the conforming hoopla of post-World War II atmospherics it was celebration of the democratic, the expressionistic, the subversive, it was music infused with race and identity politics, with the sublimation and distortion of race and sex, with urban and rural beats, Memphis, Chicago, Fort Worth, Clarksdale, and it spoke of depths of metaphysical sublimation and hunger, an anguish to feel, a barely articulate articulation. When Chuck Berry sang,

Swing low, chariot, come down easy

Taxi to the terminal zone

Cut your engines and cool your wings

And let me make it to the telephone

he wasn’t just singing about an airplane trip, he was mixing old spiritual longing with the modern condition, a sacred and secular conflation that warped the flight metaphor into something like a Ginsberg or Ashberry poem. Or when twenty year old Elvis Presley, a semi-employed truck driver, wandered into Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios in Memphis, and changed the course of popular music by singing,

Now this is one thing, baby

I want you to know.

Come on back and let’s play a little house,

And we can act like we did before.

Well, baby,

Come back, baby, come.

Come back…

you got the sense a lot more was at stake than doing the dishes. The universe was going up in flames, metaphysically, and Elvis (and guitar player Scottie Moore, and bassist Bill Black) was trying to keep time. Love, lust, have probably been standard song subjects since the first caveman whistled, but here was something extraordinarily combustible, menacing even, in the drawn-out syllables, the yelps and canine moans, against the cultural backdrop of all those Eisenhower-era teens sipping Coca-Cola by backyard pools. Little Richard and Elvis had been approximate hit-making contemporaries (“Tutti Frutti” entered the charts in December of 1955, “Heartbreak Hotel” was January 1956) and they would soon be followed by Jerry Lee Lewis, whose version of “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Goin’ On” was released in May of 1957, as Dwight Eisenhower, in the tentative but definitive first steps in dismantling Jim Crow, was sending troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, guarding African American students walking to an all-white high school. The optics for both Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard in 1957 must have been, let’s say, less suited for prime time living room watching than those of the comparatively mildmannered Elvis. But take a look at old pictures and video clips on Youtube of Richard and Jerry Lee from that era: even they were performing in suit and tie, their fashion sensibilities more in line with Steve Allen and the Anita Kerr singers than later gaudily spangly presentations of themselves, or—across the looming generational divide—the likes of Hendrix or the Beatles. The Beatles themselves were a uniformly mod-suited lovable combo in 1963, the year of “Viva Las Vegas” and the John Kennedy assassination, but within two years they’d morphed into the nascent drugginess and sitar experimentations of Rubber Soul.

By his mid-thirties, Elvis, for all his suggestive hip swivels and hair product provocations, had pretty much become relegated to the musical equivalent of the VHS, his endless string of mediocre movies undermining the otherworldly quasar of his early success. So old fans—now parents with jobs and mortgages, who viewed Elvis as a nostalgia-circuit figure of their own recently passed youth—must have taken notice of the television special comeback he mounted in 1968, performing in front of a live audience for the first time in seven years, hitting the stage in a black leather getup that made him look more like 50s-era Brando than the Beatles of their Sergeant Pepper resplendence, but belting out his repertoire of hits as if rediscovering the versatility and lusty clout of his own voice. His self-aware jokiness and leather outfit may have been unsuited to the flowing au current counterculture Beatles and Stones style, the hippies and Vietnam war protests going on in the streets, and it would soon lead to his arena-ready jeweled jumpsuit- and cape-wearing karate kicking excesses, but in 68 he’d staked out his territory and was pushing it for all it was worth. By that time, everyone was just trying to hold on, find their place. Chuck Berry’s

We had motor trouble that turned into a struggle

Halfway across Alabam’

And that ‘hound broke down and left us all stranded

In downtown Birmingham

was becoming Dylan’s

God say, “You can do what you want, Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’, you better run”

Well, Abe said, “Where d’you want this killin’ done?”

God said, “Out on Highway 61”

As with literature and the visual arts, no small part of the pleasure one derives from popular music comes from its predictable patterns, and its rejection of predictable patterns, the considerable feat of turning specificity into essentiality, the familiar into the wondrous. It’s an explicitly devotional move, implicitly political. One mission of art— maybe its primary mission, I have been thinking lately—is to declare life at its most quotidian to be to be unknowable, and then leaving it to the art to furnish its own particular meaning (whether a nonsense war whoop of “Tutti Frutti,” or Halley’s Comet arcing overhead in Giotto’s blue night sky) that has the effect of summoning the dead. It’s rebellion against any existing backdrop, a challenge to prevailing metaphors.

One problem with this idea—of art as rebellion—however, as Elvis et al must have eventually figured out, is that it has a limited shelf life. Defiance of norms in their context is one thing, but a few hundred years on, out of context, who really cares much that Candide is satire of enlightenment teleology, or thinks about Bach’s subversion of Calvinist musical norms? Maybe music or social historians know that “Tutti Frutti” superseded previous modes of expression, but after a while we’re left with the expression only. The context for the rebellion is an unread footnote.

The point is: rock music especially has always relied on the energy of subversion to counter the condition of existential ambivalence. Little Richard’s whoop, the giddy Chuck Berry lick in “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” (originally brown skinned), the siren whistle of “Highway 61” accomplish similar work: tearing down what gets in the way of feeling, foregrounding immediacy. Soon after the relatively innocent tunes of Little Richard, Jerry Lee, Buddy Holly et al began coming over the airwaves in the US and circulating transatlantically to England and back again, teaching the music of America back to itself, the songs, as a shared collective stock, took on more complex, and archly literary, forms. The LP album became the standardized format for serious artists. Hallucinogens, a thriving street culture, political vangardism, raised the ante. The music that came out of this period wasn’t so much in rebellion against the old as it was vaguely indebted to it. As curators, these bands were also going back past Elvis and Little Richard to deeper roots (Robert Johnson, Elmore James, the Carter Family, Charlie Patton, Bob Wills, Son House), averring prayer and nihilism in equal measure. And like kids who’d parlayed relatively modest inheritances into fortunes, the Stones, Beatles, Velvet Underground, the Stooges, Hendrix, the Who expanded their economies, amping everything up. Then when I started going to rock concerts in college in the 80s, you stood, as a test of good faith, as close to the stage as you could get, elbowing and leaping your way into of the arms of strangers in the madness of what would become known as the mosh pit. Bands like the Replacements, Ramones, the Lyres, Pogues, Sonic Youth, the Cramps, Leaving Trains, Lazy Cowgirls, Jason & the Scorchers, Hüsker Dü, Black Flag played at such frenzied speed and volume that you were compelled by the music’s sheer force to release yourself to it, part of the frenzy you were creating. I wasn’t a drug user, but this must have been something like what it was like: feeling the power of absolute surrender. That I also happened love Frank Sinatra, Patsy Cline, Chuck, Elvis, Buddy Holly, Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen, may have put me at odds with many dorm-mates and fellow concertgoers, but the broader musical repertory spoke of some expanded tribal attachment, each concert creating a portal into the history of everything.

A question occurred to me the other day. What was one supposed to do with that elevated feeling engendered by these experiences? It’s an odd question. I’m not sure it makes as much sense as I think it ought to. Either way, I don’t have any answer for it. You sing along. You feel, in the general sense, as Emerson—the transparent eyeball—proposed, being “glad to the brink of fear.” When you look at a Rembrandt it doesn’t so much demand viewers stand on any cliffs as it asks them to consider eternal stillness. But of all artistic genres, rock music in its purest form seems to call one to action. When Shane MacGowan, frontman of my all-time favorite band, the Pogues, sings,

Now you’ll sing a song of liberty for blacks and paks and jocks

And they’ll take you from this dump you’re in and stick you in a box

Then they’ll take you to Cloughprior and shove you in the ground

he’s implicitly enjoining us to witness and acknowledge suffering, ugliness, hopelessness, the grit beneath your skin, and—at least that’s how I see it—to stake a position. For those of us who grew up in the mashup decades of the 70s, 80s, 90s, going to see these bands that played with high-wire exhilaration, we felt gladness to the brink. We were true believers.

But to get back to my original question: What’s the point of rock music? Or is that a bad faith question to begin with? Is all that thrashing about, the ramped-up guitars, merely entertainment, a pose, a schtick, and one should no more expect music to have a point than Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, or Survivor? Yet— Yet a few answers might be suggested. 1) More is the point. Turn it up. Little Richard’s band used to play through a 25 watt PA. A decade and a half later, the Who’s PA was 120,000 watts. You can’t hear your own thoughts. You’re lost in greater and greater waves of sound pressure pushing your cells around. But volume on its own, it seems to me, points to diminishing returns, lack of meaning, the collapse of a tulip economy. 2) In its superficial disdain for mainstream materialist culture, rock, like hip-hop, also proposes an alternative materialism. Rebellion as a currency of capitalism. Graceland as the promised land. Take the Car, for example. Next to the Girl, the greatest of all rock metaphors. In fact, the first rock’n’roll song might have been “Rocket 88” (1951), Ike Turner’s paean to a new model Oldsmobile and a template for practically everything that came after: Chuck Berry, songs from Janis Joplin, the Beach Boys, Springsteen, Prince, A Tribe Called Quest. The car, like the girl, evolved as a metaphor of conveyance, of escape, transcendence, of motion as emancipation, but it’s also a capitalist motif, and rock’s adoption of it complicates the notion of rock as rebellion against the larger social milieu. Monthly car payments warrant no mention in “Rocket 88” nor “Little Red Corvette” nor in any of Springsteen’s epics of escape and survival. 3) Though much—most—of rock music isn’t overtly political, it can, in its prevailing tendency, make the political point that the world, being fraught with anxiety, insecurity, turmoil, is always looking to be upgraded. Rock music, like the church, inches toward salvation. Art does shape our way of knowing, our way of seeing the world outside itself, and making the unknowable into, well, not exactly something knowable, but perhaps tolerable. At any number of the Pogues concerts I went to over the years, Shane would lurch into the line from “Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” “They’ll take you from this dump you’re in and stick you in a box,” and the instant had the effect of bonding the tribe—the world, it seemed to me—in humane solidarity, intersecting anguish with hope before they take you from the dump. Perhaps, in retrospect, there’s a moment, thinking of such nights, when you find yourself unexpectedly responsive to the music’s accumulated force. That’s all.

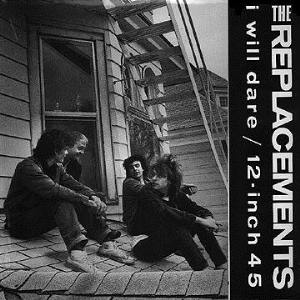

The other day I was talking to my lifelong friend, Eve, who told me a story about being on hold with customer service at Neiman Marcus, when the wonderful pop confection “Can’t Hardly Wait,” from the Replacements’ Pleased to Meet Me album, came on.

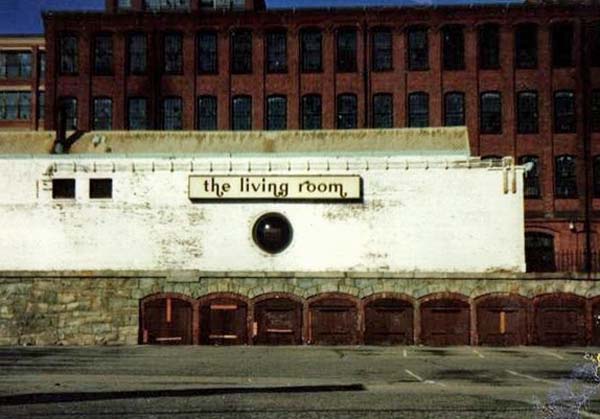

Eve and I had seen the Replacements together in Providence, in the late 80s, on a memorably debauched, wondrously cinematic night that’s remained a mythical touchstone for both of us lo these decades later. If my memory is right, the Replacements’ original guitarist Bob Stinson had been kicked out of the band and they were touring in support of Pleased to Meet Me, on the cusp of a commercial breakthrough that never quite happened. Without Bob, they were a more professionalized unit but still careeningly unmanageable. At the time I wasn’t tuned to the band’s looming identity crisis, but it hardly mattered; the Living Room in Providence, like CBGBs in the Bowery or a million other rock clubs across the country, was graffiti scribbled, possessed of a reassuringly ambient stench of cigarette smoke, b.o. and sloshed Budweiser, and Eve and I, caught in the room’s dim strobe flicker, surfed the wave of elbows, shoulders, the sudden intimacy of a stranger’s mouth two inches from your face. All these decades later discreet memories of that night still exert a stranglehold on my imagination, and I wondered if the Neiman Marcus folks, or the hold music folks, could have fathomed the song’s meaning (that absurdly inadequate word) to us. Or had “Can’t Hardly Wait,” sunk into the generational background, as “Tutti Frutti” or “Heartbreak Hotel” in our parents’ generation had a few decades before: a noise that elicited a fond echo, with little trace of its original tumult and insurgency.

“Can’t Hardly Wait” is a love song of love in tatters, as much of an anthem as the Replacements could ever muster, a pop ditty with an ashtray heart. For a band that so famously shrugged its shoulders at commercial considerations, it’s a wonder the Replacements themselves could have ok’d the licensing of the song, or that the lyrics passed Neiman Marcus’ corporate muster:

Jesus rides beside me

He never buys any smokes

Hurry up, hurry up, ain’t you had enough of this stuff

Ashtray floors, dirty clothes, and filthy jokes….

But maybe that’d been the point all along. In begrudgingly joining the mainstream, the music was less corrupted by its association with it than the mainstream was enriched by the music. Songs like “Can’t Hardly Wait” are secret bombs waiting to go off, insisting, as you’re on hold at Neiman Marcus, that life’s a messier business than you think, but we’ll get by in defiance and, as Emerson says, gladness to the point of fear. Or, as Shane MacGowan in his cigarette-and-god-knows-what-abraded voice, sings, “Then they’ll take you to Cloughprior and shove you in the ground/ But you’ll stick your head back out and shout, ‘We’ll have another round.’”

You might be interested in

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

Sojourning down American Highways via Thumb

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

How did we become this anyway?

Does the zeitgeist churn up the villains it deserves, or do the villains create the zeitgeist?

In the mid to late Sixties, along a cultural fault line running somewhere between Saigon and Akron, Ohio, villainy had an uncanny way of mixing up with what was happening in the street. Let’s take, just for the fun of it, Batman: not the comic book or movie franchise, but the old tv series. The series ran from 66-68 and at its peak was broadcast into half the living rooms in America. The cartoony villains in the cartoony show rained terror upon the city of Gotham, and concocted Byzantine plots to foil and eviscerate the Caped Crusader—all the while adorned in outlandish multichrome costumes that seemed to align with the generation’s playacting style. It was good gaudy fun, and seemed somehow connected in parody to the self-doubt beneath the era’s optimism.

Villainy is often theater, of course, with an extra dash of personality disorder. Just think John Wilkes Booth with his Latin and his bloody dagger— But even before you get to Batman, the twentieth century had had its share of over-the-top cartoony villains—If you ignore the most concerted mass slaughters in the history of the world, Hitler and Stalin in their jerk-off fetish- fantasy uniforms are as close to clowns as you can get. But as the 70s took hold, villainy, so it would seem, shed its more garish extravagances, developed a more stolid fashion sense, favoring off-the-rack suits, regulation bureaucrat haircuts, looming five o’clock shadows. The era’s most notorious exemplars, Nixon, Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell et al, came into national consciousness as get-the-sale-at-any-cost used car hawkers of the American psyche. 50s guys you’d see at the end of driveways. And in a certain lights, they also appeared to be, like John Calhoun or Aaron Burr or Robert E Lee of earlier generations, moralists of a particularly American order, fallen idealists, possessing elements of tortured Shakespearian, Miltonian, self- flagellation. I picture Nixon/Richard III, with a single light on in the White House, whispering to his own soul, ear cupped for an answer that never quite comes. Perhaps there’s no more chiaroscuro image in the history of the US presidency than that of the 37th President rattling around the East Wing one May morning at 4 am, blasting Rachmaninoff, then venturing out to the Lincoln Memorial just as the sun ekes over the Potomac. On the Memorial’s steps, students eye the glowing tips of their cigarettes, protest signs on their shoulders, as Nixon steps out of the Presidential limo. “I know probably most of you think I’m an SOB,” says the lonesome man. “But I want you to know that I understand just how you feel.” Secret Service men, dark glasses in pockets, establish a permeable perimeter. The students shuffle forward, posing questions he’s in no position to answer. His Republican suit binds at the shoulders.

Whatever else, the zeitgeist of the early 70s did seem to conjure a Nixon-like character, a symbol of Americans’ war against their own identity, and a parody of anti-parody with a talent for incredulity… In November 72, Nixon was reelected by a landslide, but a few years later a pissant break-in operation, paranoid cover-up and popular resistance to the notion of an imperial presidency, had taken down the President. And one morning in August of 74 the only President in US history ever to resign strode across a chintzy White House red carpet, flashed defiant Vs for Victory on both hands, stepped into an old army helicopter, and was hastened away over the Lincoln Memorial. Richard III was flying coach.

I apologize for the lengthy preamble. Bear with me. Sometimes an oblique approach gains higher ground. For a while now I’ve been wanting to expand upon a subjective perception I’ve had viz the current sitting president, but thus far what I’ve wanted to say has remained inchoate to me. But encoded in its inchoate quality, I’ve been hoping, is a key to getting at the same essentiality that can be attributed to Nixon. On January 20, 2017, the movers showed up and dumped Trump’s gilded toilet, fake Renoir and adult kids off on the White House lawn, and since that day habitual contextualizers, including me, have been hard pressed to contextualize the President’s place in the zeitgeist. Like penitents at a shrine we recite over-familiar flaws (bigotry, sexual brutality, narcissism, mental instability and/or incompetence, demagoguery, collusion, personal corruption etc etc etc) and hope for, if not necessarily expect, miracles of understanding to ensue. Our need for outrage is satiated temporarily; but gains in personal satisfaction come at the expense of public meaning. Of course there have been outpourings of public resistance to the new administration—protests, court injunctions, a million daily snickers, impotent impeachment proceedings—but as observers of Trumpian villainy we sometimes lose context in dense thickets of specificity. The more obsessively we tally evidence of his gross malfeasance, the farther away from its essentiality we seem to feel, or at least I do. Nixon’s sins seemed tied to a flawed character that could make one of the great protagonists of the twentieth century; Trump’s wickedness exists outside accountability, an ambient one-dimensional corruption that stymies investigation, criminal and psychological.

In affaires politiques, I generally default to the grand overview that many former history majors like me tend to take. According to the meta-narrative, grandees of politics from Pericles to Nixon reveal their ideas, flaws, ambitions, exert influence—and are thence mulched into the historical soil. Over time the dead grandees’ status may rise or fall, some new iteration of an old grandee may appear, like a straggly weed from a spared seed, and we will believe, comfortably, dutifully, that the present is to be construed out of the past’s inhering logic. But for many liberal, ruminant political bystanders, the 2016 election results made us wonder what the hell history’s logic had prepared us for. Trump was an outlier in the comfortable story about the Republic many of us had always told ourselves. He was mentioned in polite company only out of necessity, dismissed with a small cough into a hand. Every word the man spoke elicited cellular level revulsion in many folks who had accepted that the American government ran, with some few exceptions, on a bumpy but fairly predictable course.

Our verdict had been political, of course, in the the word’s most basic sense. But more than political the verdict was, arguably, aesthetic. I mean, let’s face it, on Batman, it was the Joker’s fashion sense, his self-aware anarchicness, that separated his villainy from that of run-of-the-mill larcenists and embezzlers. It elevated him to a special order of bad guy. Trump’s own vain costume (the crotch-length neckties, rehearsed scowls, tangerine makeup, Marie Antoinette combover coiffeur), on the other hand, possessed none of a cartoon villain’s self-satire and joyful mayhem. “Trump’s symmetrical but overlong tie,” says a Stanford scholar, “stands out like a rehearsed macho boast, crass and overcompensating.” It’s a jokeless joyless style, a bragging stuck-out tongue of a tie, incapable of processing irony, and void of darker dimensions of Nixonian tribulation—not only bad but tedious—not only odious but malign—an existential threat to the commonsensical decency Americans want to believe characterizes their finest impulses.

“You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style,” says Humbert Humbert in Lolita. Trump has no prose style (he’s functionally illiterate), and Nabokov could wield his own ornate prose style of course, but here’s the point: how often bad taste does coincide with bad faith. Nazis built grotesque monuments to themselves, drug lords and Wall Street novitiates adorn their wrists with watches the size of Volvos. Trump would gild oxygen if he could. Let’s say, as Heraclitus does, that Ethos anthropos daimon. Character is fate. Fate is style. Style is matter. Here is Trump, risen to the highest office of the land, interpreting his triumph as vindication of the venal know-nothing style. He’s absorbed into his corpuscles the knowledge mob bosses have.

That corrupt character, the bragging tie, can lead to a decent living too.

At the center of Trump’s I-know-you-are-but-what-am-I-ism is a question of identity. What am I? Who am I? Am I nothing? Negation presented as a question. A plea. An admission. For some writers, the presentation of this vacuity as affirmative good could make premium raw material. Pundits type as fast as he manufactures fresh outrage. Late-night comedians feast on the carcass. But from a dramatist’s perspective, what matter can be made of such character? What fresh insight would a reader gain from a novel about a soulless protagonist? A few possible angles of approach suggest themselves. There’s the political, of course. Plausibly, Trump could be sketched as the logical extension of Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn (Trump’s mentor, and McCarthy counsel/acolyte), a modern instance of demagogic tradition in American history. But Tail Gunner Joe was a maniacal prosecutor of chimeras, a perverse idealist. Too busy trying to fill the void, one guesses Trump couldn’t care less about Constitutions, governments, or chimeras for that matter. Still, the novelist or screenwriter must occupy her pages with something to engage the reader’s sympathies. The Empty Man, the feeblest of Strong Men, must somehow be relatable.

Once in passing I’d imagined writing a novel about a Trump-like huckster. I went so far as to work out the peripheral characters, how the plot would play out against an arc of the American political scene. Maybe my Trump could have a moment like Nixon’s, rattling around the East Wing at odd hours, wading into the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial, trying to plumb the depths of a quiescent soul. A cadre of vile yay-sayers would round out the dramatis personae. Kelly Ann, Javanka, Paul, Vlad, Sarah, the Mercers, the Kochs, the Steves, Spencer, Ann, Roger…. Uniform in their insatiable lust for power, these characters exude multitudinous villainy. They’d circle the Oval Office, offering flattery, procuring reality tv celebrities and porn stars for the President, helping to undo the achievements of his arch-nemesis, the coffee-colored foreign-born ex-. A twisted little lizard, Stephen M—Iago, Robespierre, Uriah Heep—so close to power he tastes it like bile in the back of his throat, writhes, kisses the ring. Javanka corners Bannon in a West Wing bathroom, threatening to kill his dog if he doesn’t surrender his FBI clearance and wipe the President’s cell number from his phone before the toilet finishes flushing. Ann, throwing back her patrician mane, chortling in self-adoration, slips poison into Andrew Sullivan’s breakfast cereal. Kelly Ann—a Jersey mob wife trying to return last year’s sweater at Nordstroms—pushes past the clerk and assistant manager, waving the old sweater like a flag. All doing their own jazz riffing on any misplayed presidential bleat. But the exercise of writing such a book, while possibly diverting, seemed entirely misbegotten, you might as well try writing a novel about a vacuum.

Demoralized, unsure where to start, I set the project aside.

What claim hath any villain to the zeitgeist anyhow? Historically, Americans’ taste in villains has run from charismatic rebels who cruised the country lanes and shot up the road signs (Bonnie and Clyde, the Joker), to antinomian demagogues who would tear down the temples (Daniel Shays, Ann Hutchinson, Father Coughlin…). Engendered in the country’s Jeffersonian Revolutionary spirit has always been a fetish for destruction as a means of renewal—the restoration of an ancient white-pillared America that never really did exist. In this light, the Trumpian moment is nothing new. John Calhoun, William Jennings Bryan, Father Coughlin, Sarah Palin were progenitors. Indeed, one is sure Trump hardly is aware of historical precedent (I’d bet his bogus fortune he’s never even heard of William Jennings Bryan). An accidental populist, he’s an unwitting, vacuous vehicle for populism’s most toxic Coughlin-, Palineque strains. To my mind, the pressing question, however, is whether casual brutality endures as the defining fashion of the zeitgeist, warping our national psyche, or shall it be buried along with the corpses of McCarthy and Coughlin and Trump, remembered as a fleeting deviation from commonsensical decency?

Let’s not attribute to pathologies what might be attributed to chance. Maybe in fact we’re too quick to accord Trump the ambient influence he believes his birthright. Sure, Senate and House Republicans who should know better have made an unholy alliance with him, furthering their own agendas, becoming accomplices. But as a demonstrably unpopular populist (losing the popular election by 2.9 million votes), he was churned up for any number of reasons (identity politics, vagaries of the electoral college, crooked gerrymandering…) that disqualify him as the people’s legitimate representative, and, lest we forget, a change in three or four counties countrywide would have flipped the electoral results too. Thesis creates antithesis. The rickety old democracy, we like to think, exerts its old normative self. The king rides naked through the streets, proclaiming his preeminence. But Executive Orders are overturned. Paris accords remain in effect. Little Stephen Miller, hissing on tv, is escorted from the building, kicked to the pavement. The press returns fire. Investigations grind on. Senators vote on evidence. Impeachment prevails. Alec Baldwin hilariously upends blow hardism. The crotch-level tie is scorned. Crassness and villainy may hold sway for now, but a counter movement pushes back, an exuberant and inspired opposition engaged in democracy. The Republic, in greater jeopardy than any time since Nixon’s, or perhaps since Reconstruction, struggles to re-right itself, and, if history can be regarded, the Republic may survive the threat, and may yet endure for another few hundred years. Let us pray.

Zeitgeists are not kind to their villains.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

Charles Manson and his followers settled in at the Spahn Ranch, in Los Angeles County, in the summer of 1968.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the