In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the entire country.

More

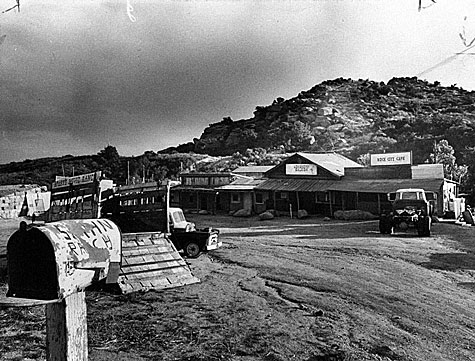

Charles Manson and his followers settled in at the Spahn Ranch, in Los Angeles County, in the summer of 1968. After the nights of August 9 and 10, 1969, when followers killed seven people in the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders, group members drifted away from the ranch. Some, including Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, Catherine Share and Patricia Krenwinkle, continued to be devoted to Manson, long after his conviction and incarceration. Another member, Linda Kasabian, testified against Manson and was instrumental in securing a murder conviction against him.

Our scene begins on August 9, 2019, the fiftieth anniversary of the Tate-LaBianca killings, and two years after Charles Manson’s death of respiratory failure and colon cancer, age 83.

From a payphone outside a Save-a-Lot, in Marcy, New York, Squeaky Fromme is speaking to Catherine Share, who’s at a friend’s house outside Dallas. Squeaky is bundled up in a coat, her red hair whipping around her face. Even at age 70, she’s recognizable as the waif who pulled a gun on President Gerald Ford.

Catherine, 75, sits on a comfortable sofa, dressed in an embroidered blouse and mid-length skirt that bespeaks middle-class respectability, stylish silver hair framing her face. She wears light makeup, soft pink nail polish.

Squeaky fishes through a canvas bag, finds some change, sorts through it, deposits coins. Her voice is heard through static:

SQUEAKY

People walk around dead, Gypsy. They think they’re alive but they’re dead. You touch them, they’re cold. We were alive to the birds, the air, you and I. Trees recognize us when we walk by.

The phone goes dead.

CATHERINE

You there?

Squeaky’s voice is heard through static:

SQUEAKY

(aside)

You can’t use nickels and dimes in phones these days.

She deposits two quarters.

CATHERINE

Hello— Hello—

SQUEAKY

Charlie—he resisted the things that were destructive to the environment. Who gets to say right and wrong, you know—

CATHERINE

My parents were resistance fighters, you know.

SQUEAKY

To what?

CATHERINE

You kidding, Squeaky?

SQUEAKY

I’m not.

CATHERINE

I was born in France. My father was Hungarian, a violin player. Budapest Symphony. The SS would’ve yanked his teeth out, cut his and my mother’s genitals before they shot them. I carved an X on my forehead because of Charlie.

SQUEAKY

All the girls did X’s.

CATHERINE

Then Charlie did the swastika.

SQUEAKY

Yeah.

CATHERINE

Would I have done it if he asked? A Jew?

SQUEAKY

It’s just a symbol, Gypsy.

Catherine traces the space between her eyes where the X used to be. She looks in a mirror, applies some lipstick. Her friend signals to ask if she needs a drink. Catherine declines.

CATHERINE

I don’t have a single picture of them.

SQUEAKY

I threw away all the pictures of my parents a long time ago. Good riddance.

CATHERINE

I used to try playing Bartok Violin Concerto No. 2 that my father used to play. It’s extremely difficult.

Catherine plays air violin. A beep is heard on the phone. Catherine looks at it, presses a button. Her friend leans over and demonstrates. Another voice is heard:

VOICE

An inmate is calling with a prepaid card from the California Institution for Women. Will you accept the charges?

Call is from Patricia Krenwinkle (Big Patty, Katie).

CATHERINE

Yes. Yes. Patty. Katie.

PATRICIA

Squeaky? Gypsy?

SQUEAKY

We’re here. We’re here.

PATRICIA

How’s the weather?

SQUEAKY

Since when do you talk about weather.

PATRICIA

Just talking.

SQUEAKY

Remember the weather hitchhiking down Alameda Boulevard, Pacific Coast Highway, the old lemon groves, Katie—

PATRICIA

Our voices filled the canyons.

CATHERINE

(singing a Charles Manson tune) When I was a little boy

I used to hang my feet In the muddy waters

That run through your streams Get on home, get on home

Come on home little children, come on home

Patricia and Squeaky join in, their voices rising in girlish melancholy choir. It stops abruptly.

SQUEAKY

Those songs are still in the canyons.

CATHERINE

You know, you lie out there in the sun, all the colors washed away, these lizards and coyotes and scorpions turning into symbols. Hopalong Cassidy comes riding out of the heat coming off the dirt road, and you’re tripping your brains out.

CATHERINE

Remember Clayton Moore that time?

PATRICIA

Oh yeah, yeah.

CATHERINE

Supposedly they did some shooting there. The actual Lone Ranger.

SQUEAKY

Charlie didn’t like it one bit.

CATHERINE

Clayton Moore was wearing the mask when he came to the ranch. A weirdo among weirdos. We were all wearing Indian costumes, tripping. Tex asked why he wasn’t in black and white. Clayton Moore said the Lone Ranger was in color one year. No, it was black and white, Tex said. Only we lived in color, Tex said. He’s talking to the Lone Ranger, who’s wearing this mask. We’re wearing our Indian costumes. That’s fucked up. Tex wanted to kill him too. Tex used to wear real six-shooters around.

SQUEAKY

He would have.

PATRICIA

He showed him a knife.

SQUEAKY

What did he do?

PATRICIA

He laughed. Clayton Moore laughed.

SQUEAKY

Wrong thing.

PATRICIA

He would have killed him. Tex. One more second. Then Clayton Moore drove off in his silver car. Hi ho, Silver.

SQUEAKY

Clayton Moore was lucky to get away with his life.

PATRICIA

Tex took a shot at the Lone Ranger’s car with his six-shooter. Remember?

CATHERINE

It got so, I don’t know, after a while the sex got spoiled. It got all mixed up with who wanted to fuck who. A bourgeois nightmare. Possessiveness. You don’t want to fuck the guy who wants to fuck you. It got sometimes where you wanted to leave. I didn’t trust myself to be who I was. I had to be someone someone wanted me to be.

SQUEAKY

Charlie was tender. People don’t know. He was a tender lover. His body like a snake’s.

CATHERINE

Your breasts felt like they were having their own orgasm.

SQUEAKY

Charlie was real.

CATHERINE

Charlie was a salesman, parody of a traveling door-to-door guy. A petty crook. A parody of Christ, playing parody crucifixion back of Incase Place.

PATRICIA

We bought everything in his travel case.

CATHERINE

Are we really talking about that?

PATRICIA

Let’s not.

CATHERINE

Could have been any one of us got picked.

SQUEAKY

When are you free? My parents had disowned me, so I disowned them.

CATHERINE

My parents committed suicide in a cellar in Auvergne as the SS was closing in on them.

SQUEAKY

You don’t have to live your life the way people say. Live the way the universe tells you, why don’t you.

CATHERINE

We wanted to get caught, you know.

SQUEAKY

Don’t be ridiculous.

CATHERINE

Charlie knew it. After a while we didn’t want to live lives of resistance. We were tired of it.

PATRICIA

Tex was the one who lived it. He was a killer inside. The rest were only on the outside.

SQUEAKY

That’s a lie, Katie. Nobody put that knife in your hand. You put a knife in your hand. No one made you chase that woman into the yard, no one held your hand while you stuck a fork in her belly. Over and over. No one made you go the next night, scribbling the walls with blood.

CATHERINE

Well, maybe no Tex, no dead Sharon Tate. No dead LaBiancas. He strung Sharon and the hair stylist together. Tex shot the kid in the car. Sometimes I can’t remember the names of all the others.

SQUEAKY

My mind wasn’t controlled. No way.

PATRICIA

I was in a daze.

SQUEAKY

Well, my mind and body were clear.

PATRICIA

Well, after the LaBianca thing, we hitchhiked and got picked up by a real nice couple. Sort of like the LaBiancas. Chatty. The woman had chipped fingernail polish and one eye bluer than the other. We took a wrong turn, and everybody laughed. Tex would’ve killed them. Taken their car. Leslie was asleep in the back seat. Tex was the one who tied up everybody both nights: Sharon, the LaBiancas. Tex climbed the pole, cut the wires. Tex killed em.

SQUEAKY

We were fighting a war to save trees, oceans, ground. Who sent all those kids to be killed in Vietnam? What was that about?

PATRICIA

That’s stupid.

CATHERINE

Is it? An acid trip, religion, an orgy, has to climax. Living in the desert, wandering around looking for holes in the universe, eventually you’ve got to find a real hole.

SQUEAKY

Or give up, you’re saying.

The phone goes silent. At her friend’s house, Catherine presses a button on the phone. We see a woman calling from a cellphone in her truck, driving backwoods trails in Maine. Her voice cuts in and out. Linda Kasabian.

LINDA

Well, well—

SQUEAKY

I don’t need to talk to that woman.

LINDA

Squeaky—

SQUEAKY

Judas.

LINDA

I just wanted to talk to Catherine and Katie.

CATHERINE

Hush. For god’s sake—

LINDA

I was just looking for some place to set my head down back then.

PATRICIA

We were all lonely, Linda.

LINDA

Yeah.

PATRICIA

Charlie happened to saunter down Ventura Boulevard, a nothing little twerp, trying to fit in, trying to create himself, but he felt our loneliness. He played it that way. It was our own loneliness that drove us to madness and despond. I felt it in my intestines, my neck muscles, my vagina—loneliness, I was desperate to be part of the jumble, the singing, the disorder, the smells of hamburgers coming from the pavement, but I was nothing. Instead in my loneliness and wantingness I became a monster, or someone acting like being a monster could bring love to the world. I was chosen to kill, and that’s what I did so I’d know how to be loving. All our loneliness was unquenchable. That’s what you try to explain but can’t.

CATHERINE

Stop feeling sorry for yourself, Katie.

PATRICIA

Am I? Every night for 17,634 nights, I climb into a bunk, pull a blanket over myself, try to claim a sliver of sky, and shiver myself to a sleep that never really comes, paying for trying not to be lonely. I deserve it. I do. But Gypsy—you go to a nice house, call your children on the telephone like a mother nothing un-mother-like ever happened to, go to your pretty church, drive a pretty car, like nothing happened. Like you never showed your beautiful tits in that movie, never cut an X on your forehead, never shot up a Western Surplus store to get a couple hundred rifles to hijack a plane and kill a passenger an hour till Charlie got out.

CATHERINE

I was the driver.

PATRICIA

You would have killed Barbara in Hawaii too. You know it. Maybe Clayton Moore. But it so happened you’re where you are. No offense. Seriously. You’re still me with another ending.

LINDA

Did it ever occur to you Charlie knew who had it in them? You? Me?

CATHERINE

Or he walked by, eeny, meeny, miney, moe.

SQUEAKY

We all had it. Eeny, meeny, miney, moe.

LINDA

Because is the question and the answer.

SQUEAKY

Linda. Can you please stop talking nonsense please?

CATHERINE

We were dancers and beauty queens and daughters of spacemen and violin players and nuns and students and mothers— That’s what we were. Was it because? Because because was only so much of it. Charlie gave his little Dale Carnegie patter to every pretty girl with dirty feet and stringy hair sitting at a bus stop on Melrose Avenue. Strummed his guitar. He cast a wide net. It wasn’t us just because— How many dirty lonely kids were on Melrose and Vine in 1968? Hitchhiking the PCH?

LINDA

I was nothing. Twenty years old, divorced a couple times, one kid, another in the oven. Twenty years old. I would have ended up a file clerk or checkout in a pet store. Gypsy brought me to the ranch in July, and one month later Wojciech Frykowski crumpled down on Roman Polanski’s lawn in front of me, gurgling, his eyes like dried up fruit, you know like comes in a plastic bag. His fingernails with someone’s skin under them. He was handsome, more delicate than in pictures. Tex stabbed him a hundred times. I watched.

CATHERINE

There was meaning— There had to have been. It’s too much to think otherwise.

LINDA

What’s meaning supposed to mean?

A disembodied voice comes on the line.

VOICE

The inmate has five minutes.

PATRICIA

I got out of nun school in Alabama, and was crashing with my sister in Manhattan Beach, till I met Squeaky at a bus stop. She went by Lynette then. Lynette. Me and Charlie and Lynette were crashing in Topanga Canyon, and sometimes drove out into the desert in Charlie’s black bus. Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona. Shoplifting Twinkies and keychains with names of the tourist on them, tripping and playing guitars and tambourines. The first morning I slept at the ranch I woke up with someone’s arms around me. I didn’t care whose. I turned over and kissed her, and touched her hair. My mouth was dry from the dust, but hers was like an oasis, it tasted like Wrigley’s. We made love on the boxspring while someone cooked breakfast on a hotplate, and dogs trotted in and out and we flicked off the flies. I didn’t know whose mouth it was, but it knew me, it knew everything I was thinking and wanted from life, and nothing else mattered except that it kept on kissing me. It belonged to me, and there was a voice as soft as music you don’t know where it’s coming from in the night.

You might be interested in

In the decades following her trial for the murder of her father and step-mother, Lizzie Borden walked the streets of

The Centaur’s skin, all moon-grained in an idle mirrorreminds him of an ailing heartdrawn out in sundry mortal quests.

Between 1974 and 1976 Patricia Hearst, UC Berkeley student, scion of the prominent California Hearsts, became the most wanted fugitive

On November 24, 1963, smalltime nightclub operator and sometime underworld figure Jack Ruby walked into a Dallas police station, and

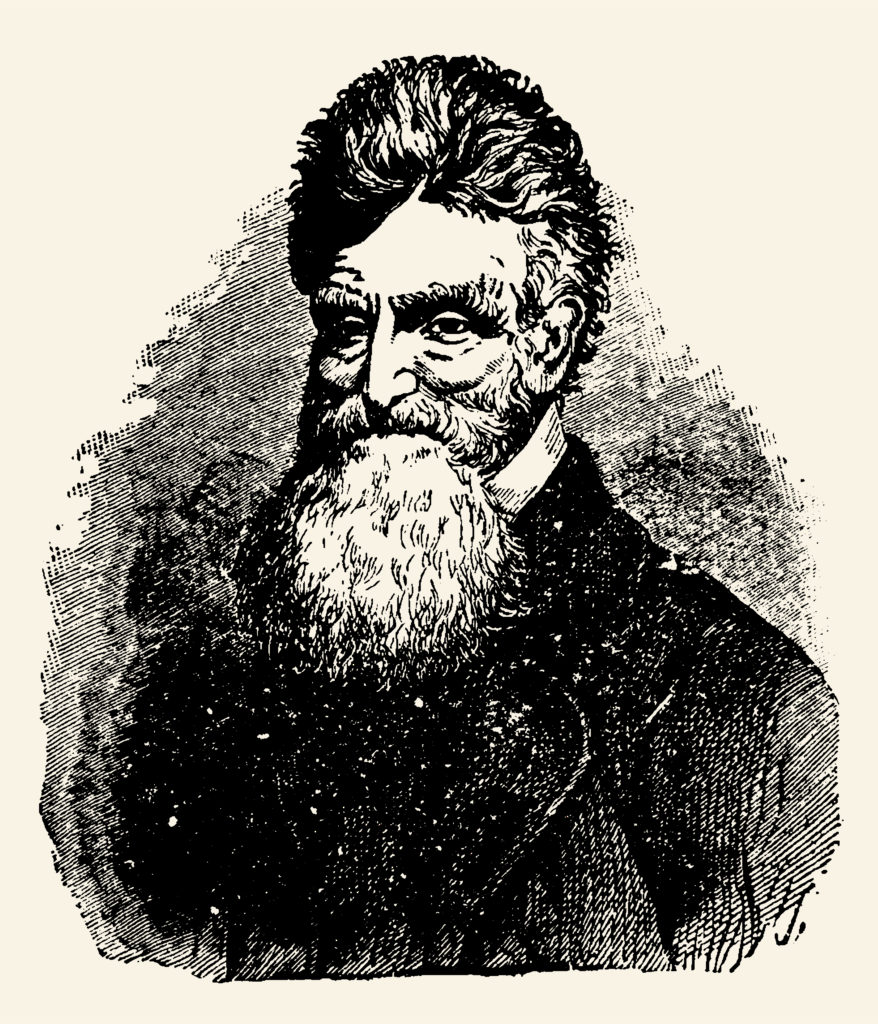

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The events of those days became a prelude to the Civil War.

6:30 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

A prophet ought have many sons, fecund of visions, loins and wars. Nazarene wind he carries in his nostrils, possesses fingernails of clay and embers, carries his beard with the Lord. Prophets heed no influence from mastery of man, temper their souls with no carbon of civilization, they come from deserts where the Joshua tree and sidewinder thrives, word of God in their spleen, armament of swords and brands and pikes arrayed against the legions of enemies. Born of sand and blood of serpents, the prophet girds for eternity.

I, grandson of Captain John Brown, son of Owen Brown, heir of Jacob and Lazarus and the Baptist, taking my commandments from the mount, had six and twenty sons, half dozen daughters, thirteen wives, I came from meager backings, meager houses with three chairs at the table, ceilings so low no beaver hat is worn, working vegetable tanneries on outskirts of towns, the hides of beasts like pages stiff and bloodied on the scales, fumes settling in the winter’s iron temper. In time of the ancient prophets, washerwomen collected buckets of urine for the tanners trade, essence of man giving skin of beasts new life. Outside towns was heard the bleating of the cattle, grunting of the hogs, confused beasts in pens. Thence stripped to skin and meat, becoming tack, shoes, satchels, serving man even unto death. I am 60 years old, having been born to this world on May 9, anno domini 1800.

7:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas

I walk the plains, Kansas territory, Iowa, creeks and poultry yards, sound of body and mind. Whosoever is to suffer is to suffer unto me. I am the enslaved, toiling in fields of cotton, rice plantations, I dedicate myself to their deliverance as if I were them, they me. The Israelite, the Ethiopian, the Indian. All as chattel, but, like me, chattel of our god, not of men.

Those whose war is made on me, so is war wrecked upon them.

8:05 pm, October 16, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

I am grown ancient as the sphinx, in need of rest, folded into hollows where the shoat and lamb lay down in shadows. Ask my God—it is not for me to rest, but fight till my enemies are vanquished. Wagons, loaded in the darkness, start along the Chestnut Grove Road from out of Maryland. We carry Sharps rifles, pikes, provisions for the long campaign, in the darkness oxen chains clink, the twenty-one men of our army snort in their sleeves, muffling their sounds. Guided by the moon’s dim gleaming, light rain, we follow events already determined by providence, follow vectors of our pikes and rifles. Along the road soldiers sing hymns, ditties, and stop to relieve themselves in the woods. Our mules and oxen, riled in their foreknowledge, mutter in low protesting voices, under the scattering stars. In my youth and young fatherhood, I lived in the hills, nomading around Connecticut, New York, Ohio, Missouri, Massachusetts, Iowa, eventually making my living in the wool business, the tanning business, the farming and husbandry business. A wife died in childbirth, and my children, many, likewise, their graves scattered across fields and homesteads in the lowly wind. Why ought I to think of them now, their graves grown over and unmarked? I sense them in the shadows, their voices singing to me from the trees and sky, reminders of a life once lived, but long expired now.

10:30 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

I ride this criminal’s wagon, upon my own casket, nodding at the crowd. The Hebrew Bible tells of the prophet Obadiah, who had forsaken his wealth in service to the prophesies of others. At risk of his own life, he protected the other prophets from the Babylonians and their Edom allies. Though thou exalt thyself as the eagle, says the passage, and though thou set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring thee down. So will it come to pass that other prophets, beyond my time upon earth, will bring down the Southern planters who exalt themselves and corrupt the land with bondage and butchery of human life.

Now I ride upon my own casket, bound in ropes and cuffs, and smile at those who jeer at me, as Christ, bearing the burden of his cross a millennia and half ago, bore the jeers of men, women, children. Let me witness the street vendors and the hurdy-gurdy men, let me witness this carnival one last time.

7:40 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

We steel ourselves, making our minds hard in our work. In cover of darkness, we wait amid fields of bloodroot, spiderwort and the black-eyed susans. The dirt road wends its way down to the creek, where devils sit in cabins by the fires. My sons, Frederick, Owen, Salmon, Oliver, Watson tend the horses, nuzzling them, feeding them sugar cubes by hand. The soldiers of fortune, Thomas Weiner, James Townsley, smoke their pipes, drawing pictures in the dirt with the barrels of their rifles. Our chests breathe deep the chilled night air. Thy will be done. Two days ago in the District of Columbia, Senator Charles Sumner was beaten near to death on floor of the Senate, by a maniac South Carolinian. Sumner is the most exquisite man, handsome and stubborn in his beliefs about the Negro question, and in his speech spoke in stentorian tones of war in this forsaken territory, with its gullies, creeks and scattered settlements. Slavery might be introduced into Kansas, quietly but surely, spoke the senator, without arousing a conflict; that the crocodile egg might be stealthily dropped in the sunburnt soil, there to be hatched unobserved until it sent forth its reptile monster. And for that he was beaten near to death? Man may always chose to fight to the death over a scrap of barren ground, but Kansas land is sacred, fighting for it doubly brutish. The stars tell of affliction, and grow uneasy in the sky.

It’s not too late, says Salmon.

He is nineteen, a lanky youth with a fuzz of beard over his chin and upper lip, a sensitive boy.

It is hard to be so careful, brother, Owen says. But harder still to be righteous. I know myself, he says. I have not learned to be righteous enough.

Owen protects Salmon from vicissitudes, and reads the Bible to him, explaining parts Salmon puzzles over.

Salmon whistles for the screech owl. I wonder what our mother thinks of us, out here at night, he says.

Oliver looks up. He is the youngest, seventeen, and given to swings of mood, a violence that comes, I wager, from such circumstances. He grumbles, paces down the road, impatience rising.

10:35 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

On either side of the street, my wagon passes regiments belonging to our United States government. The townspeople stare, their faces querulous, pinched. The soldiers wear neat blue uniforms, dust on their shoes, they are young, my sons’ ages, mostly, and do not, I apprehend, fully understand their representation of the authority of government, that their lives are given to enforcing that charge. I meet their looks, so they might see the man they will hang. They too are the condemned, the nooses sound around their necks. I ride upon the box that shall be my resting place, rocking to and fro as if on a jaunt in the country.

9:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

Some years ago in Springfield, Massachusetts, I sat in the Sanford Street Free Church, listening to Mr Frederick Douglass. To many, the prospects of the struggle against slavery seem far from cheering, said Mr Douglass. Eminent men, North and South, in church and state, tell us that the omens are all against us, he said. Afterwards I talked to him about the state of the negro in this country, of which he has special knowledge on one hand, but from which he is insulated on the other, surrounded as he is by the white abolitionists. In the community in North Elba, New York, where I lived for a time, I came to know the negro as a friend, and worked to teach the negro families to plant and harvest, and thence in Kansas became Captain Osawatomie Brown of the Pottawatomie Rifles, with an army of a thousand thousand men, who fight for manumission. Tonight we seven men eat our dinner of cornbread and cold joint. We watch the smoke from the chimneys of the Dutch Henry settlements, the devils unaware of our battle plan.

Oliver goes to the wagon, his back straight against the slats. Wake me when the regiment’s ready, he says. He is a good son, honest and good-natured, zestful in fullness of his youth.

10:37 pm, October 16, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Without opposition the men move into position and take the railway bridges, the armory, arsenal and rifle works. By god’s hand the campaign has commenced, and so we act in accordance with god’s word, and with our knowledge of we are about to accomplish. By tomorrow the world shall know of our accomplishment. Here written the demise of negro captivity.

12:02 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

I give the order for a company to be dispatched to the home of Colonel Lewis Washington outside town. A servant in shabby livery opens for the knock, and, making the servant a hostage, one of our men points a Sharps at the head of Colonel Washington, General George Washington’s grandnephew, a tall heavy man in nightshirt who struggles out of his bed to find his carpet slippers. Our detachment commandeers a sword and hilt given General Washington by Frederick the Great, and dueling pistols given by Lafayette, symbols of the fame of our enterprise. The negroes of the estate, unprepared, consider themselves captives, and greet the news of their emancipation with skeptical turn of heads, awaiting additional information.

Upon return to the armory, Oliver says to me, Captain Osawatomie Brown, I present to you the great grandnephew of General George Washington, and these spoils of war. Let war commence according to your wishes, captain.

1:21 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

The common carrier crosses the the bridge above the Potomac, gray smoke pressing from beneath the covered truss, the locomotive’s pulmonary pant coming in the darkness. Watson signals the slowing train to a stop. In the shadows a man leaps down, coming to investigate. This too our army has anticipated.

Shoot him, says Watson.

Oliver holds the Sharps with sure hand. For the sake of men in bondage.

He squeezes the trigger.

So shall it be done, brother.

The man buckles, wedged between the train and bridge timbers. Oliver lowers the Sharps, his unshaved face unrelieved in its stoic appreciation of the scene.

Oliver and Watson wave the train on, so as not to arouse suspicion, it goes westward toward Wheeling, the caboose light vanishing along the tracks like a submarine fish.

A questionable omen: the dead man is a negro.

In the rifle works and armory, the men are cracking open crates of rifles, arms for our army that at this moment is amassing itself in the hills of Maryland and Virginia against the enslavers. Our revolt signals a time when the present shall become history.

2:00 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Colonel Washington, the hostage, begs to see his wife, making promises of keeping silent. And so ought he to fear for his life, for so it is written, And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.

Our tactics are the equal to our strategy.

11:30 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

There are sounds you do not hear lest you pitch your ear to them: distant yowling of dogs, crickets and cicadas in their exquisite yearnings, the grousing of cattle by the creek bend. There are steps that are taken that cannot be untaken.

10:40 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

I shiver off the chill, trying to shimmy the coat over my shoulder, assisted by the jailer’s hand. What is an instant of comfort in life, in an eternity of sleep? I fear not. I fear not. In this box, I am to join my children, my wife, the ancient ancestors of the desert, pilgrims of exodus, readers of the burning bush. There was a time one winter in North Elba, when the snow was falling outside the windows, we were inside by the fire, there were preserves and hams in the cupboard, our neighbors were the negroes who came, and we sang the old hymns and prayed together and ate supper together. But now that I am to be no more, my thoughts, my memories, my moral fire, must pass on. I only held these things for my allotted days. The gallows are in the field, on a low hill outside town. The structure, made of new timbers, is there in full, mountains behind, white farmhouses in the vast fields, and a bright fall sun warming the grass and leftover stalks of corn. So much ceremony attends the extinguishing of fellow man. The crowds of Virginians, the newspaper writers, tourists, the mounted cavalry and infantry soldiers, sentinels, have come to witness and ensure the last moment of a man’s existence. To make example that one man might not start a war. Wars, howsoever righteous, are started only by authority of government, and under the admonishment of laws.

11:35 pm, May 24, 1856, Franklin County, Kansas Territory

A door is knocked upon, presently answered by an old woman of forty-five or so, her visage querulous in the light of her oil lamp. Her hair, color of dust, is undone about her head, her mouth disclosing no obligation to sentiment.

Do you know where I might find Dutch Henry’s? I remove my straw hat. Yonder.

She gestures with her eyes, not her head.

Watson and Oliver rush in, scripture quoting, pushing the woman into the table, showing their pistols. She hollers to a man we cannot see, who emerges from a little room off the kitchen, a smallish slaver with pig eyes and slack set of his jaw and shank of hair sprayed over his sweating pate, who sets upon me with fists until Watson holds the Sharps to his head. It is necessary to act swiftly, with improvisation and instinct. Watson ties up the slaver up (his name, we discover, is James) and holds the wife without tying her, a courtesy to an old woman. Five half-sleeping boys come out of the two rooms, a few no more than ten, one almost twenty, I reckon. The oldest pleasant enough looking, a full foot taller than his father, with curled hair like wood shavings and a chin like a judge’s. A gun hammer clicks: Oliver. Never has this boy aimed a gun at anything. His hand is steady. Their mother stares at me without tears, as if my authority could possibly affect the course of events.

I do not speak but wait for my sons to apprehend my meaning.

If our enemies are killed, as in days of Kings, might their sacrifice atone for the sins of those who enslave countless hundreds of thousands, beat them with the cat-o-nine tail, and take their bodies as their own? Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.

The slaver James follows us unresistingly, perhaps curiously, into night air. The three oldest are selected by Watson, who signals for them to follow. Without warning, their mother throws herself at his feet, begging him leave at least the youngest. Brute animal noises are coming from her, and she clings to him, who tries to kick her off, with neither scorn nor care. The boy—youth—is old enough to procreate another generation of dirty slavers—man enough, with wide shoulders, faint mustache—he looms in the doorway without speaking. Unknowing where to go, he might bolt. Watson allows the boy back into the cabin, the two pass in the doorjamb, slightly nodding, their eyes meeting an instant. I watch with no outward protest.

I walk ahead, taking the three remaining down the road, surrounded front and behind by men of our company. God, I am certain, is never more with us than he is at this instant. His eyes are on us. He marches in our company. I pray silently for His sign. James breaks toward a stand of trees, but in an instant Salmon’s upon him, grabs his pantleg and tackles him to the ground. Owen, not far behind, raises the broadsword, coming down upon the slaver’s shoulder, and again upon his leg. James holds up his hand, and another blow is dealt, this time by Salmon, who hacks him around the neck and head, till the slaver sinks down, his breathing slowing. In the darkness, his clothes are blackened, blackness spreading into the shirt’s hollow whiteness. I step forward, feeling nothing, feeling no burden, no grief, no discomposure, no remorse, and remove the pistol from my jacket and in a single motion deliver a single bullet to the slaver’s forehead. I have become who I shall be. The two boys (their names Drury, William) understand everything, they have moments to plead with their god for forgiveness and atone for their sins, naturally they try to run, but my boys seize them too. They are stronger than their father, but we are stronger still.

7:00-10:00 am, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Armory employees, local Virginians, Marylanders, come in through the gates, and to their confusion are taken immediately as hostages, watched over by Owen, Oliver and Mr Dangerfield Newby, the mulatto, in the engine house. We treat them as we would comrades, talk to them of our plans. Owen, Oliver and Mr Newby engage them in conversation about the insurrection, telling them that negroes, being naturally industrious and good natured, will make good neighbors and friends. Most of them are not slaveholders, they claim, but the slaves are happy in their station. What they do not know is that slaves in the vicinity will have heard the news, and will be joining our army by the hundreds, thousands, equipped with new rifles and more bullets than the Federal army used to fight off the British. This revolution will spontaneously ignite revolutions still more encompassing, these grow into a singular all-consuming war all over the South, devastating the corrupt and benighted regime of the Southern slaveocracy. Outside, the sky brightens, a thin line of yellow creases the river and riverbanks, the bridges and ramshackle collection of buildings that make up this town. It is well nigh upon the time for the arrival of the freed slaves. I order Mr Newby and Watson to the gates to check.

But the moment they are away, an argument is heard, and the tattooing exchange of guns.

I hasten to inspect the source only to find Mr Newby’s body, twisted upon itself, lying in the street, his mild and honorable face turned toward us as if pleading for the great cause. Flies already cluster around his open eyes. His fingers are curled around a staff he’d had with him a moment past. The second casualty of the day. Two negroes. As I stand at the gate, bullets careen off the armory walls, fired by the self-appointed deputies outside.

Negro reinforcements will have to fight their way through these marauding ruffians to reach us, but I have no doubt their determination will see them through.

10:50 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

To be young in this country is to be lost. To be young in this country is to learn the country’s sin. But, fear not, God heeds not the deceiver nor the pirate. Looking upon what I see at this instant, this land might appear unagitated. It is a land of farmers, mechanics, merchants, scriveners, inventors, ministers, fish mongers, husbands and fathers and spinsters, all living in industrious accord. It is a land of mountains and farmyards and the roil of cities. But, mark my words, beneath outward harmony is concealed evil’s portent. My body on the gallows will awaken those who are young. They know the work ahead. The cotton factor, Northern banker, Southern planter, the overseer and driver, will suffer in the war to come. For, as in Scripture, the indignation of the Lord is upon all nations, and his fury upon all their armies: he hath utterly destroyed them, he hath delivered them to the slaughter.

1:00-2:00 pm, October 17, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

One hour ago, my son Watson was alive. He was a young man, of average height, nimble in his step, never shy from work, sure of his opinions in the way of young men. Last I saw him in full vigor of his youth, he was offering a prisoner water from a ladle. At my order, he walked outside, past the gate and Mr Newby’s body, under a flag of truce. We wished to negotiate honestly and honorably with the men of Harpers Ferry. Under the flag, Watson was shot. A man aimed and shot him in the chest for no reason other than he was standing there with a flag. He stood an instant, taking stock of his wound and, I like to think, his God, and fell not fifty feet from Mr Newby. We are given no choice but for our war to go on. We will wage it to the last, avenge the deaths of Watson and Mr Newby. A prophet rises beyond the congress of death, and beseeches his God with the resounding thunder of conviction. Yet another young soldier of our army, Bill Leeman, loses nerve, and deserts his post. I watch him slip out from behind the rifle works, and wade into the Potomac for his escape, plunging under the water. I watch his progress through the window of the rifle works with no envy of his freedom. Nor do I think to shoot him. Then the men that shot Watson Brown turn their old muskets and shotguns on Bill, hunting him as if he were game. They would kill him with pitchforks or shovels if they could. Stricken, he stumbles and climbs onto a rock in midstream, holds to it, half submerged, his leaking blood slithering like snakes in the brown river. Outside, still more townspeople are gathering, ragtag militia we could easily defeat if our soldiers did not desert. Finally a decision is made. We leave some prisoners in the rifle works to their own devices; Oliver and I select others to join us in the sanctuary of the engine house, and set an oak beam across the door as a barricade. Outside, for hours, are heard the sounds of dogs and roosters in nearby yards, the muttering and shouting of men. Some authoritative voices offer to negotiate terms of our capitulation, but no victory is won without casting off of one’s fondest garments. There are protracted periods of silence, punctuated by birdcalls and the rivers, the sputtering of bullets.

6:30 am, October 18, 1859, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

The Marines mass outside, fixing bayonets with twists of wrists. We regard their serried ranks, uniforms of sky blue, scarlet stripes on their trousers, through chinks in the engine room door. Their whiskerless faces are firm, afraid, in morning’s gloom. It will be said I am a madman, but it’s the madness common with the awfully sane, the heart that seeks to break the husk of earthly constraints. I pull on General Washington’s sabres. I aim at Harpers Ferry mayor and fell him with a single shot, bent bodies heaped in the streets.

Gathering our remaining forces, holding our remaining prisoners, it is right to die with the tender mercies of a madman.

11:00 am, December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia

The cadets gaze sidelong toward those assembled for the event, and momentarily glance up at me as I mount the gibbet in my carpet slippers. The hangman’s breath has a whiff of onions and lager, he is of short stature, and wears boots of chapped and dusty leather, and is courteous in expression and movements of his hands. He unloosens my hands, shakes mine, and offers the noose to my head, permitting me accept it in my terms. I stoop in accommodation of the sack, till even the sun is blotted out. Prophets wear the vestments of beasts of the wilderness, skins, feathers and scales, and attire themselves in the whirlwind of their prophesies. Martyrs, in knowledge of eternal life, wear coarsest cloth of creed against their skin, they go down to rivers, cleansing themselves in jubilation and exculpation. All men face eternity, expended in fiercest drive against heavens’ murderous stillness. All men suffer fate of their birth to count down the number of their days. Yea, I have finished counting, and count my death as just endowment in service of those days.

The drumbeat of the drummers grows louder, plaint of rivers, howls of chains.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

John Murrell, prolific bandit on the old antebellum Natchez Trace, had a talent for masquerade.

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the entire country. With bombs. He almost succeeded.

Part One:

The Ballad of Pine Island

A MOMENT

Behind the wheel, he scans the onramps and turn-offs, lines of mailboxes, stuffs himself with fries. The wipers half clear away the moth and grasshopper bodies that have burst in gaudy blots against the windshield. He contains immensities of the land, the noble extent of rivers and bluffs, multitudes of time. He reckons with omens, prophesies.

HISTORY OF MINNESOTA

Time persists, one supposes, without much calculation of its persistence. Twelve thousand years ago, this land was scraped clean by withering glaciers, and the sky was charged in voltaic blue. After a millennia or two, caribou, saber-toothed cats, mastodons, bison started wearing grooved paths in the tundra and spruce forests, the profusion of species giving assurance of their durability. Soon thereafter—a few millennia—bands of Ojibway and Dakota (the Mdewakanton, the Pezihutaziz…) began traveling overland through forests of black ash, elm and silver maple, following rivers and lakeshores, building summer lodges, trapping sturgeon and whitefish in willowbark nets, and spearing the plump mottled pike. In those days French and English traders were also coming up the St Lawrence, canoeing through the churned-up surf of Huron and Gichigami, and up the Bois Brule, portaging to the headwaters of the St Croix. Following smoke threads from village to village, they traded beads, blankets, firearms and brass kettles for beaver and weasel pelts. Soon posts and forts were set up along the rivers, and the baled pelts sent south to the Gulf of Mexico or north and east along the St Lawrence. From the Iroquois reductions in the east, Jesuit missionaries pushed deeper inland, toward the edge of the known world, lank-haired mystic-eyed men in worn black robes and the buckskin vestments of the Iroquois and Huron. The priests, with their squirrel guns and jerked bison and French Bibles, spoke quietly, earnestly, and copied down the words of the tribes. They lived among the Ojibway and Dakota, learning their languages, playing hutanacute with the men, and bartering with the European traders. Soon came even more white men, clearing encampments in the pine forests along the St Croix and Rum, making way for bunkhouses, cookhouses, steam-powered mills and dancehalls.

In north country, along the river valleys, white pine forests flourished in silty loams and glacial tills, going as far as you could see, like a singular green shroud. All day long, fifteen hour days, twenty, two-man teams worked the saws, the sound both far-off and inside your head, snapping branches, surging riotous crashes like the underground rumblings of Hades. Come spring, with the ice thawing and the roads cleared of snow, logs came spilling downriver—in rafts so extensive you could nearly cross the St Croix from the Minnesota to Wisconsin side without touching a foot in the water. Then the camps would be dismantled, the whole operation picked up and moved still deeper into the forests.

Territory constitutes currency; and in 1851 an agreement called the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux transferred ownership of much of Minnesota’s southern and western lands to the United States, effectively ceding Native control to the whites. Seven years later Minnesota officially became a US territory, and, in 1858, a state. In a matter of decades the forests would be cut down, almost wholesale, leaving black stumps and worked-over hills slick with oozing batter-like slurry. The Dakota, the Ojibway and less populous tribes could not be done away with so efficiently.

By 1862, earlier treaties with whites had become irrelevant, at least to government agents, and the Dakota, swindled out of money and provisions, running out of land and options, began raiding white storehouses and villages, escalating resistance until more than two hundred white settlers were killed, and as many taken captive. Houses were burned, children kidnapped, hacked to death. The leader of the insurgency, Little Crow, and his followers moved west to Dakota territory, but, understanding the inexorable force aligned against them, surrendered to armed Minnesota volunteers. Within a week of the surrender, three hundred and three Dakotas had been rounded up and sentenced to be hanged. Back east, Abraham Lincoln, distracted by the Civil War, commuted the sentences of all but thirty-eight. And on December 26, 1862, those thirty-eight were hanged in the largest single-day mass execution in American history. The Minnesota Dakota reservations were shut down, the remaining tribespeople exiled to reservations in the West.

In that same year the only railroad in the state consisted of a measly ten mile track connecting St Paul and St Anthony (part of the future Minneapolis). But by the 1870s and 80s, thirty-one hundred miles of track—eventually absorbed into the Great Northern line—was running north into Duluth and the Mesabi Iron Range, west through the ancient glacial lake basin of the Red River Valley to Minot, Devils Lake, Havre and Spokane. Business interests had always been business interests, and from their inception federal agencies (the General Land Office, Bureau of Indian Affairs) were established to guarantee pacification and domestication of Native people, opening up new territories to immigration, and new sources of revenue to the government. Immigrants from Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany came pouring west via Detroit, Chicago and Davenport, steaming upriver into St Paul to claim their parcels. Initially, the settlements may have been little more than a dry goods store, a tent brothel, a couple sod houses, but the industrious Northern Europeans were soon building new towns, with churches, saloons, banks, schools, orphanages, restaurants, madhouses.

The majority of new arrivals were, denominationally speaking, Lutherans and Calvinists, who were predisposed to a certain commonsensical, rational ecumenicism. But might one suppose such pioneers were also operating with the cultural and religious dexterity of anyone far from home trying to navigate a new land. The circuit-riding mystics of the late nineteenth century, for all their faith-healing and patent medicine pitches, were, after all, bringing news of the land to its newest denizens who’d found themselves, quite wondrously, shipwrecked upon its inland shores. These settlers had come not to revive lives they’d had back home, they were stumbling toward weird new identities, creating a history that eclipsed not just their own, but that of their adopted land.

PINE ISLAND

The town of Pine Island, Minnesota, is reached by US 52, a four lane highway coming up from Charleston, South Carolina, that eventually makes its way through Illinois, Iowa, and the so-called Driftless area, a region geologically defined by natural springs and fishing streams, narrow valleys, bluffs and steep hills left unflattened by ice sheets in the last glacial age. As it stretches north into Minnesota, 52 bisects the state diagonally, tracing old Highway 55 on the way to Fargo, Minot and the Canadian border.

The town itself is situated in the middle fork of the Zumbro River. On 55, south of the Twin Cities, take the County 11 Road exit. It’s quite a small place, population numbering three thousand, with a hardware store, local library, a few barbershops, a mobile home park, a grain elevator, and a performing arts center called the Old Pine Theater that gives it cosmopolitan airs, some might say. In the early days of the twentieth century, Minnesota dairy farmers had been interested almost exclusively in butter and milk production, but Pine Island, set apart from other communities in the state, produced enough cheese—cheddar, Swiss, muenster, Colby—to fancy itself the cheese capital of the world. And as if in demonstration of this fact, one local cheesemaker created a monster three-ton cheddar—four feet six inches high and nineteen feet in circumference, made from the milk of 3300 cows. But in time rural crafts like cheesemaking became economically unviable, a relic of a vaguely embarrassing past, and by the 1960s, sixty percent of the residents were commuting to Rochester and the Twin Cities. But still it’s the kind of small town psychically content in its confinements. A future Nobel Prize winner or Secretary of State, attentive to cosmic vibrations, dreaming of the wide world, may occasionally break the orbit of a town like Pine Island and become something almost impossible to fathom, but lives here are passed mostly in modest employment and pleasures. You might drive to a nearby Indian casino for a spree, or settle into a Saturday night, couple beers, assured of the moment’s constancy and durability.

LUKE

From 1991 to 1999, Lucas John Helder attended Pine Island 5-12 school. He was a middling, pleasant student with nascent artistic interests and a tendency to stick to himself. Five feet, nine, a hundred and sixty-three pounds. Clear skin. Engaging smile that sometimes bespoke a certain lostness, or misty focus. An interested teacher or classmate might have detected something out of the ordinary in his small acts of rebellion, his playing his Discman too loud, tapping his fingers on a desk, but to most kids of Pine Island he mixed in as a good-natured, generic enough friend who would offer a quick saluting wave, and goofy self-deprecating laugh. Darla at Family Hair Styling buzzed his hay-colored hair, emphasizing a hairline that ran perfectly straight across his forehead—the standard jock look. He played Panther football and golf, and hung out at Betty Sue’s Cafe after school. Luke also liked music and liked to pour over CDs at Rochester Records, mostly alternative, and sang in the concert choir. He was into occasional partying, drinking, smoking weed. In summer he performed contraband cannonballs at the municipal pool, and teased his younger sister, Jenna, about her flirting with every single boy on the basketball team. Maybe ten years from now his classmates would have trouble remembering him, but sometimes on the football field now, on the warm August nights that spilled hastily into fast-cooling September, it thrilled him when the cheerleaders shouted his name, which rang out louder than others, he thought, as they clapped and did the splits and performed their choreographed routines. He pretended to be indifferent, but taking off his helmet, squeegeeing sweat from his face, his heart would be going like crazy, and, glancing into the grandstands, he grinned like an idiot at the good fortune that had befallen him. Fifteen Panther cheerleaders levitated as if by some stage trick, kicking their legs in their pleated maroon skirts, and cheered in unison, Luuuukke Heeeelder. A cooling breeze came across the Zumbro River. Luuuukke Heeeelderrrrr….

Luke and his mother, Pamela, and Jenna and their step-father, Cameron, lived in an A frame out on 515th Street, an unpaved country road four miles from nowhere that twisted through grazing pastures and sparse stands of willow windbreaks. In winters, he waited for the school bus in balls-clenching cold, stamping his feet, trying not to breathe in the arctic air that perforated his throat like icepicks and sucked his pores dry. Sometimes in the morning he’d be slow getting dressed, and ended up walking, or Cameron’d offer him a ride. The Accord always, always, was colder inside than out, and the combined breath of the two of them—the one young, the other made temporarily young by his easygoing affability—frosted the windshield, which they tried clearing off with the meat of their four clenched hands. They let time go by as the Accord negotiated the country roads that rapidly filled in with geometrically flawless drifts, the new snow cresting old banks.

On Friday or Saturday nights Cameron went to the Legion for a beer or two or three. For a Vietnam vet who’d grown up with the protests, the war, Woodstock and all that hippie crap, he had a talent for not getting all righteous or monotonous about his history. Luke could appreciate that. Cameron didn’t treat him like a stepson, nor did he try to pretend he was his actual blood son either. Together they went fishing out at Cannon Falls, Prior Lake, North country, bass, muskies, talking politics, the movies, sports, religion, school, things like that. Agreeably aimless, drifting conversations.

On his graduation night, June 1999, Luke was pretty charged up. When his name was announced, he bounded up on the stage and shook the principal’s hand—a broad robustly mustachioed man he’d had zero interaction with over the last four years—and gazed out at his classmates with a bemused, giddy superiority. He pumped a fist and raised his hands overhead, earning a smattering of applause. Triumphant, he returned to his chair in the H’s, next to Wendy Hertzberg, a big girl with a birthmark that covered half her face. Behind the seniors, in lawn chairs and blankets, parents and friends had spread themselves out across the football field in an array more motley than their corralled progeny. Luke scanned their ranks—their adult faces blunter, duller, scoured of high school daydreams or dopiness—and the entire town of Pine Island seemed to float away, drifting off in its mysterious and impermanent intimacy.

That summer he worked construction alongside Cameron. He wore a hardhat, dayglow vest, and lugged shingles and buckets of nails around construction sites all over Rochester for seven fifty an hour. When he came home his entire body was coated in plaster dust, and an unidentifiable grit filled his pores. As a bonus, Cameron let borrow the Accord, which he took to the pool. He’d been hanging out there with a girl he’d met at a football game a few months ago, a tallish blonde with slim legs, green-blue eyes and a cockeyed pirate face. Irresistibly kissable. Her name was Skylar Cassidy. He would make out with her behind the pool’s cinderblock changing clubhouse, and run his fingers over her riotous breasts under her bathing suit top. It wasn’t just her kooky legs and bitten-down fingernails that made him feel weightless, giddy, but the way she would stop and look into his eyes, as if she were burrowing deep inside a part of him. Her mouth tasted of chocolate milk and chocolate chip cookies and cigarettes, her face was like a holy relic.

Waste of my life, Luke said to her about his construction job, trying to impress her.

I don’t like when you talk like that, she offered.

Well, I’m going to do big things. You’ll see.

Like what?

You’ll see.

He’d started writing songs on the fake Telecaster he bought with his construction money, and sang into the tape recorder in his bedroom. Anxiety/society. Relax/Ex-lax. Alimony/Give me your money. Channeling Kurt Cobain. The Blew EP, Bleach, especially, before the band sold out, pretty much. Before Kurt started looking like a thrift-store Brad Pitt, and before the decent-but-not-the-Nirvana-he-loved Unplugged. At Rochester Records, Luke bought pirated Sub-Pop 45s, Love Buzz, Sliver, from behind the counter from a clerk dressed like an accountant with a single stud in his cheek. He played Sliver incessantly on the Silvertone record player his mother had when she was a kid, the dust collecting on the needle like a tiny animal. Kurt’s wretched longing came through the dust and through the speaker, unmediated, gnarled, it was as if the songs themselves didn’t even exist, Kurt’s howls came from a mysterious well, the way Skylar’s lips and tongue sometimes conveyed the longings of Biblical generations. Maybe someday he could write songs like that that weren’t just songs, he told himself. The greatest convolution/ Brain pollution/ I’ll tell you my solution/ Embrace confusion. He was coming up with rhymes and melodies, bass lines, staccato jabs of snare, a stutter bass drum, his brainwaves were going full force with some secret power he couldn’t control. One afternoon he wrote three complete songs, one, he thought, as good as Negative Creep with its squalls of guitar and Kurt’s self-aware howls. Luke’s own singing was more straightforward than Kurt’s, maybe more melodic, he felt. Still, he was straining to bring the feel of winters around Pine Island into the sound, like earlier Minnesota bands he was reading about (the Replacements, Hüsker Dü, early Soul Asylum), where you heard snow sifting across downtown streets, car horns deadened in frozen snowbanks. When Bob Stinson, the Replacements original guitar player, died of organ failure a few years ago, broken-down and destitute at thirty-five in an apartment grimy with unwashed dishes and heroin apparatus, Luke had written a tribute to him for English class (Bob was so good at being a person from another planet that people on this planet couldn’t play in a band with him) and gotten a B+. He was letting his hair grow out. No longer the ROTC, FCCLA or football jock look.

Lately his and Skyler’s lovemaking had been developing new patterns of inventive versatility. They were on a slab of cardboard in the woods behind her parents’ house. She was on top, and he could count her fillings.

Would you rather time travel to the future or the past, he once said to her.

Will you tell me? she asked.

What?

Past or the future—which one?

Oh, there’s no such thing as time, he said confidently. Past—present is a fiction to tell ourselves to make things make sense. Do you want to get married?

When?

Tomorrow.

I thought you said there’s no such thing as time.

I hate you.

No, she said, yawning, her fillings black and gold deep in the warm cavern of her mouth, I will not. She was still on top.

When?

At home Pamela Helder watched Guiding Light, The Price is Right. She knitted scarves and comforters and baby hats for neighbors and her sister’s kids in Silver Lake. She cooked dishes with Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom soup, and baked cakes made with tomato soup, from Betty Crocker recipes. Sunday dinners after church were roasted chicken, mashed potato, pot roast. As a family, they sometimes took little trips to St Paul, Milwaukee, and Cameron whistled How Much Is That Doggie in the Window, and Pamela held the map in her hands, keeping an eye on the signs. These trips, with their sing-a-longs, Luke and Cameron’s talk about fishing, Jenna’s complaints about boys, were always annoyingly wholesome, but he tolerated them, at least their family didn’t fight, or the fights were sublimated.

One day Skylar showed up at Eric Upgood’s wearing dense blue eye shadow plastered over her latticed lids, like paint worn into battle. Her long hair was cut in artlessly girly bangs, the blond tips dyed blue. A candle-like scent came from her skin, an ethereal easy-going essence that messed with Luke’s considerable powers of concentration. The band practiced in the basement of Eric’s house, and Skyler had been coming along to hang out there a lot, like their very own Yoko, sitting cross-legged in a gigantic beanbag, reading a comic book and every once in a while casting a beatifically absent look from her blue-shadowed eyes. It’s a story how I’m supposed to feel because you told me to, Luke sang into the mic, pouring himself into the words, closing his eyes and letting the jagged chords tumble out of him, Bm, C, D, Em, F sharp diminished, his fingers finding notes he’d struggled to find a couple weeks before. It’s a rare wind when the time comes, a never ending train. Run away, run away, he sang, and when the other guys came pounding up behind him with bashing cymbals and Eric’s fingers running up and down the bass’s frets, he could feel something real coming together. Like it must have been when Kurt and Krist got together. Unlike Yoko, Skyler was their good-luck charm. On days she wasn’t around his mind wandered, he’d be missing her legs, her tight narrow bum, caustic breath, the blue gaze. But he admonished himself to not get too tied down, not to let himself give into feelings that got in the way of his vision. They talked for hours about how Kurt would have ended up a car mechanic if he hadn’t made it as a musician, about Luke’s own chances of being a real musician. She listened with encouraging intensity, asking about Aberdeen, Kurt’s influences, that kind of thing, her breathing matching his, as if any little conversation between them might spark wildfire.

In September, his mother, Cameron and Jenna crowded into the Accord, and drove an hour and a half to the University of Wisconsin-Stout, singing This Land Is My Land and Love Shack all the way, like they were taking one of their family trips. In the dorm Luke introduced himself to Matt, his roommate, who was a big easeful guy, wide shoulders, mischievous dimpled grin, with a born salesman’s genius for making you feel every word you spoke was solid gold. Easy to like, he could have been a logger or a gym teacher, Luke thought. If he didn’t exactly fit Luke’s typical friend profile so what, the two of them quickly became friends, going to North Point for dinner, pigging out on burritos and pepperoni pizza, talking about Matt’s family back in Kenosha, cars, girls, fishing, football, and Luke telling him about his own football exploits, which seemed a million years ago. In their room, Luke tried new out songs out on Matt, strumming the Tele, while Matt, highlighting his marketing textbook, tapped his foot in approval or, more often, tendering a baffled earnest look that showed he wanted to understand. In the scheme of things Stout may have been a lower tier school, but Luke truly admired his professors, who seemed to him shrewd manipulators of their inmost thoughts, which were then presented for public benefit. He was taking Intro to Art and Design, Ceramics I, Philosophy of Religion, American Cinema, Fly Fishing. Dutifully he filled his notebooks with unbroken lines of notes, asked questions and speaking up with gathering self-assurance and a sense of his own powers of articulation. He stayed up late reading, finishing papers, smoking doobies, taking in information he’d had only the dimmest awareness of six months before. He absorbed the intricacies of glazing and firing, class struggle, national/cultural identity, gender and sexuality in movies etc etc. Even in fly fishing class, he was learning about conservation practices, and lately had come to the revelation that the muskies he’d caught with Cameron, swimming along the unshadowed bottoms of frigid northern lakes, must have been as covetous of their own existence as he was of his. He even met a couple cute Stout girls who were spiritually, politically nimble (there was a knowing carnality in their absolution of Bill Clinton in the Monica affair), that made him forget Skylar for the moment.

In some ways Stout was an institution like the church, he told Matt from his top bunk, with its orderliness and hierarchies of priests and nuns and diocesan bishops and monsignors and cardinals, with the beautifully martyred Christ and the beautifully virtuous Mary at its cultish center. Only at Stout instead of monsignors and cardinals there were deans and professors and TA’s and campus police. Instead of Christ and Mary at the center there were beautiful books and classrooms and ideas, he said.

I love you, dude, said Matt.

Don’t people have to believe in something? Luke asked. Otherwise, what’s the point.

Asking the wrong guy.

Lately Matt had been hanging out with friends of his from business, and Luke, left to his own devices, found himself eating alone at Commons—Stout’s other cafeteria across campus—eyeing the students who looked so assured in their goofing off and preening earnestness. He couldn’t imagine he could ever be like them, easy and loose and witlessly amiable in their friendships. Homesickness sometimes took Luke by surprise. To ease the dull spasm of it he’d get a Greyhound back home.

Of course a guy like Matt wouldn’t understand. Looking out the bus’s window at the concrete strands of highway, the gray unmowed no-mans-land of the median strips with their staggered Sumacs and effluvia of shredded truck tires and fast-food wrappers and the occasional mattress or a baby seat shed from onrushing, overburdened vehicles, he wondered if he himself had ever been capable of mastering anything as pitiless as faith. Did the people in the cars—these strangers, families, couples, delivery people, salesmen, with their unfathomable inner lives, their tumult and misgivings and spasms of love—ever make peace with faith, their souls no longer contending with powers greater than their doubts?

Back home a few of the old rituals did give him comfort. Sometimes when he was home the band would get together in Eric’s basement, almost as if he’d never left. Then he’d take Skyler out to the movies like in old days, and cruise aimlessly in Cameron’s Accord, past the high school, down by the mucky Zumbro, considering the landscape’s old and familiar assertions. More and more, however, he holed up in his old room, and locked the door behind him. He cradled the Tele, strumming the same chords over and over, content with a single droning C major. He’d sleep late, noon, one, two, using up time he didn’t know what to do with. Not long ago, he’d been sitting in the Old Pine balcony with Skylar, sucking pieces of popcorn from her lips—their love playing out as love was supposed to—but sometimes when she called the house these days, her lulling sexiness and sudden enthusiasms filling the space in his ear like the sea-moan of a seashell, he ended their conversations abruptly, more content with the Tele and the room’s commiserative shadows.

One morning—or was it afternoon already?—he was half asleep when a disembodied commotion, like the clang of a train bell, startled him. Something very odd, or at least not explicable (there were no trains within miles). He yawned, and watched some shadows playing across the yellow-papered wall of his room that looked like old men dressed in some type of dark robes, with ropes tied around their waists. Abstractions, hallucinations, spirits, the randomness of shadows? But almost immediately the sun came through his half-open curtains, and the shadows dissipated as mysteriously as they’d come, leaving no sign of what an instant before had been vivid, otherworldly but unmistakeable. He slid the covers down over his chest, and, reaching for the Tele, sitting on the edge of the bed, returned without pause to his previous unhaunted, unbothered state of half slumber, as if whatever he’d just seen, or imagined, or conjured, was nothing more than an interpretive error, a temporary hallucination.

VARIETIES OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE

Luke had been a churchgoer. Meaning, Pamela and Cameron used to take him and Jenna when they were kids to St Michael’s in an effort to civilize them, as much as to impart specific scriptural training. Cameron was a semi-regular churchgoer, but despite his talks to Luke about Christ and Mary and Catholicism’s abundant social goals and its misunderstood history, Luke’s interest remained at most speculative. Even as a kid it had confounded him that anyone could worship a half-dead half-naked son of god (not even the God) or his confusingly virginal, blank-eyed and perhaps frigid mother. Of all the people who ever lived—

They talked about religion a lot when they were fishing. For a while it was their main topic. Christ’s resignation to his fate, Cameron explained, was the scaffolding of the entire church, an entire religious and presumably economic movement that had been gaining inevitable-appearing authority for over two thousand years. You had to respect that, he said.

He cast a line out over a submerged stump, and slowly reeled it in, repeating the action over and over in an undeviating cadence.

Not have—

No, of course, he said. Not have—

Lots of wars because of it, Luke said.

That’s so, said Cameron, pulling in a little brookie.

For a while Luke had been an alter boy in training, to satisfy Cameron. It didn’t last, but Cameron was the type whose faith was in no rush.

Maybe there would have been wars no matter what, Luke said.

You could respect something that started as a bunch of misfits stirring up trouble with the local banks, and became the most successful mass movement in the history of civilization, Cameron said.

Hn pulled the brookie from the stream, six inches, cinched the hook from its upper jaw with his pliers, and set it loose in the shallows. It lingered on the surface an instant, undulating in the murky water, then flicked away. Overhead clouds scudded, the sun on the teasel behind them made it shimmer.

At Stout, Philosophy of Religion met on Wednesday and Friday afternoons, in the basement of one of the oldest buildings on campus. The course’s teacher, Angela Loosig Smith-Andonian, a hip thirtyish assistant professor, had a bright and colloquial way of illustrating her ideas in the air with a chalk nub in her fingers, as if she were writing on an invisible board. Rose-colored eyeshadow dusted her lids, matching her lipstick, a whiff of linden and rhubarb issued from her skin. All semester, around a stained conference table, she led them in discussion of everything from Zoroastrian traditions to modern Christian liberation movements, Islamic and Jewish philosophies, Buddhist social movements, her knowing cigarette-roughened chuckle enlisting them in her worldliness.

In comparison Luke knew that his own brand of old-school Catholicism, or agnosticism or whatever it was, felt tepid, hopelessly provincial and perhaps, in her eyes, a joke. No professor had to tell him that Catholicism was filled with ancient incantations, mumbo-jumbo and gaudy superstition, and in its current incarnation was refuge for provincials like, he hated to say it, Cameron. Anyone could see it was a fairytale, he said one day.

A slight admonishing smile stretched over her delightfully imperfect teeth.

We’re not here to debate that, Luke, she said.

I am, he said, not as impertinently as it probably sounded.

You stand up for yourself, don’t you.

Her thin upper lip came to rest upon a purple-chalk-dust-covered finger.

I just think Christianity survives as an institution only as long as people go along believing literally that a human being was raised from the tomb, he said.

It was his favorite class, she was his favorite teacher.

The Zoroastrian point of view, she explained it one day, was the closest approximation of what he understood the physical planet to be, given what he knew of it, and his sense of what existed on the other side. There were forces in conflict in the world. Call it darkness and light. Asha (the main spiritual force) derived from Ahura Mazda (the uncreated creator Wise Lord) as a force to prevent the force of druj (chaos) from establishing itself. Have a Nice Day as cosmic revelation. Walking around campus, pondering the subtleties of Zoroastrian scripture, he found himself in a trance, going back to the dorm and playing his guitar with a blaze of new chord changes.

Come on, dude, Matt said one night. Maybe turn off the amp or something? he suggested, being practical as he always was. People actually want to like you, you know.

Fuck ‘em, Luke said.

Yeah, yeah. Matt went back to his work. Just passing the message along, he said.

Luke hopped off the bunk, flipped off the amp, hit G sharp minor on the upstroke, B major on the down, picking the chords apart in arpeggiated notes down the neck like a Boston song or something. The gesture seemed immature, and he grinned at Matt with a chastened shrug.

A few nights later he bolted up in his bunk, with a yelp that put an end to the slumbering chanty of Matt’s snoring below.

What’s up, Lukey? Matt called.

Nothing.

Come on, Lucas. Jesus.

Forget it.

Then why did you wake me out up out of a dream about Eleanor Sabelko?

Sometimes I see these figures is all.

What the fuck? I see Eleanor Sabelko in my dreams. Or did before you woke me up, motherfucker.

Thought you’d want to know.

You had a bad dream.

It’s not like a dream. They are coming to see me.

What’s coming to get you? Come on, rock star, get some sleep.

You might be interested in

The Klan in my backyard.

The Centaur’s skin, all moon-grained in an idle mirrorreminds him of an ailing heartdrawn out in sundry mortal quests.

Annals of weird old America: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln & its strange aftermath.

And you whose face so famously winces . . .

John Murrell, prolific bandit on the old antebellum Natchez Trace, had a talent for masquerade. He appeared variously as an itinerant preacher, slave trader, and abolitionist, and frequently murdered his victims rather than leave witnesses. He may or may not have planned a slave rebellion meant to ensconce him King of the South.

Don’t go down to no rivers no ghosting hour. Murrell down there, a sylph, take you up, he will, slipping through swamp oak, cypress knees. Strip your Spanish gold and shinplasters from your satchel, roll your corpse in shallows where the crawfish go.

Murrell the highwayman. Murrell the revenant. Murrell the horse thief. Murrell the preacher pushing back his black preacher hat, his grin saying lord’s in heaven and salvation’s at hand, praise lord. On his hand branded HT. A long stream of tobacco mark the cross in dust. Praise lord. He preaches, exhorting, sacred harp, Lord a mighty on high, scripture-voiced. He whips the locals up. Making the crippled limp. He says, Come on down here m’am, be baptized in this hogshead. Ain’t my lord fussy. Passes the preacher hat in the clearing. White, black, Chickasaw, octaroon, melungeon, Choctaw with their brides-to-be, don’t go down. Don’t go down.

By morning horses gone. Someone’s a corpse. Along the Trace, someone’s always busy being a corpse. Horses unhitched, unharnessed from the staves.

Sells stolen horses like cornpone. Freemen ganged in chains on the block, praying their way down the river, faces like pig iron, faces like mountains. Used to be that house nigger strolled free long Natchitoches Street, head high as a water moccasin. Murrell shows his teeth don’t bite. Sells stolen house niggers like cornpone.

Murrell’s gone, up and down the Trace, Jackson’s Military Road, he went. Keelboating down to Vicksburg, Natchez, Vidalia, New Orleans. Old Arkansas territory, below the 3630. Plunder as harvest of rightful goods by men of strength. Subsisting in shadows as long as frigates. Sleeps nights at the stands, pepperbox under a pillow, squirrel guns stowed in the buckboard, preacher hat on a post, twisting blood out of shirts till staining creekbeds color of the sun. A man who knows his fate has the high hand. Came down a boy from Tennessee, he did, slick-skinned, his boy’s mouth born for larceny, folks did say. Way an egg is born to fly.

Dreams they seize you up, set you out on a bark canoe, past loess cliffs outside Vicksburg, where wildcats, gators, bears daren’t go. Outside a Delta cabin, old hounds and whores lounging, his wife a pup with legs slung over a fence, daughters gone spreading watermelon rinds in the poultry yard. A pen of stolen horses, hogs grunting like Second Coming. Black robe missionaries went native by St Catherine’s Creek in Revolutionary days, these days sons and daughters, Jesuit foreheads, Jesuit hands, go about in buckskins, breechcloths, silk top hat. Revenants too. From Loyola days. They come to him, John Murrell, pay him tribute. Tobacco. Rum. Sacks of French and Spanish coins. Flour. Sometimes a man in iron collar. He runs the southwest now, Memphis to Baton Rouge, midnight boarding flatboats in the pork trade, whiskey, no one ever knows what happens to the kid on watch, serrated knife at his throat, a single motion, his voice stilled in the talking river. Riled herons talking in the trees. Moon passing across the ancient sky. Stop at the levee camps, five masked highwaymen take every damn slave downriver, sold at reasonable discount to Choctaw and Cherokee, dressed as white as white men, their own big houses. Round up a coffle, peppermills to heads of the slavers kneeling pleading for their lives. Slavers don’t like being dead any more than any man.

Murrell. His name rises from the quicksand and the graves. Law won’t ever catch him. Revenant from El Draque days, half privateer, half scalawag, half man, seeking to avenge cruel trick of mortality. Hangings mos’ ever’y night in the woods, you know.

Somewheres. A swaying. Bodies a trash harvest. Rotting on the vine. Only the planting counts.

One night a hundred men, hundred fifty—Mystic Clan—come round his cabin in blue of a gibbous moon, set off the sleeping hounds, their deep-throated barks like gulps. Mouths eating his corn, taking his hospitality, singing Shinbone Alley, Jim Crow, motley gangs of melungeons, levee camp Negroes, Negro preachers, Spanish poltroons with Spanish beards. He holds sway, banjo playing. He walks among them. They take the whiskey like holy water. His clan. All men his. He says, Remember John Murrell. Flesh and blood. All up and down the stands, the levees, niggers take him for his word. Don’t act what you think, act what blows through you like a hurricane. Jacquerie come any day now. Any day. Look at the brand on my hand. I am free. Here Today. Look the color of my silver nitrate eye. John Murrell Emperor of the Southwest, takes his rightful throne on Gallatin Street, waving his scepter, whores come round with prayerful hands, businessmen wait to kiss the hem of his coat. Be blessed before they start the hangings, they call forces against the new empire before it can be born. All world knows John Murrell, come down Gallatin Street, every slave rise up, rise up, oh lord, let there be blood and carrion in the new age of the stars.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

It was a time of nicknames.

Bonnie Parker was nineteen years old and been married four years when she met Clyde Barrow in the winter of

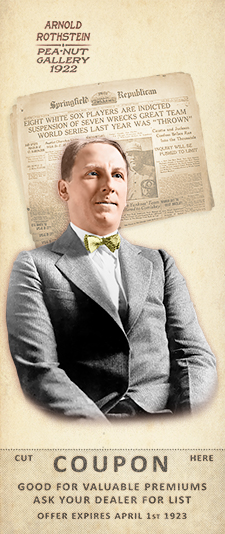

In 1919, Arnold Rothstein was the king of New York. His fingers were in everything: casinos, girls, booze, fixes. Then came the World Series.

Part One:

Apprenticeship

I t was a time of nicknames. Baseball players, gamblers, politicians, theater people, kids in hydrants, kids cannonballing into rivers. Conferred by physical freakishness, character, a lisp, a fastball, a hemline. Hump, Chick, It Girl, Shoeless, Rajah, Bugsy, Beansy, Legs, Titanic, Big Train, Big Brain. Arnold was Big Brain. Since he was a kid. A way of level gazing. A way of imagining. Preternatural equipoise.