The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

More

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don’t know.

Apocalypse, noun apoc·a·lypse | \ ə-ˈpä-kə-ˌlips plural: apocalypses

- one of the Jewish and Christian writings of 200 b.c. to a.d. 150 marked by pseudonymity, symbolic imagery, and the expectation of an imminent cosmic cataclysm in which God destroys the ruling powers of evil and raises the righteous to life in a messianic kingdom

- something viewed as a prophetic revelation

- a great disaster

—Merriam-Webster

Naturally, talk of apocalypse is more lively these days than at any time in recent memory. Ends are on everyone’s mind. There are, of course, people who will tell you that such ideas are best left out of enlightened liberal conversation: climate change, racial injustice, political mayhem, unending wars, being human problems with human causes, not something stirred up by a glowering retribution-minded desert god. Yet the conversations keep coming up, and the idea of god as a controlling presence, as an apocalyptic being, literal or metaphoric, is endlessly enticing even in 2020. The twentieth century theologian/ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr, who was always on the lookout for links between verifiable and eternal worlds, put the modern existential implications of the apocalyptic metaphor front and center: The apocalypse, he wrote, “is a mythical expression of the impossible possibility under which all human life stands.” And in some ways, the implications of “mythical expression” in Niebuhr’s framing might be the same for us in the twenty-first century as it was for the early Judaeans who first conceived of apocalyptic imagery: we stare into the cosmos with awe and trembling. Niebuhr’s winking, “impossible possibility,” points to a crossover of hopelessness and hope, the daily duality of the human condition. Life now, as ever, hangs in the balance.

Historically speaking, there have been plenty of apocalypses to go around. For three millennia, give or take, the apocalypse idea drifted in and out of favor, a readily mutable and spiritually resilient shorthand for temporal anxiety, an enduring myth by which existence might somehow be understood as transcending bodily constraints. The franchise, as Niebuhr hints, has always traded in all kinds of dualities: hope and despair, possible and impossible, end and beginning, salvation or damnation, annihilation and rebirth, submission and domination, reality and myth. We sift through these in hopes of finding a mythology apposite to our times. And as apocalypse metaphor de jour, the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is unsettling to us not just because of the havoc it wrecks in our streets, homes, workplaces, performance spaces, schools, stores and old folks homes, but because of its disruption of the habits and social customs that have often offered fellow feeling in other would-be apocalypses. Metaphorically, coronavirus, like the 1918 flu before it, ramifies into a diabolical test of social solidarity. In midst of other catastrophes that have tested our forbearance—in wars, pestilence, genocides, to name a few—physical touch, the glances of strangers on the street, offer countervailing human connection. But coronavirus exaggerates havoc, robbing those who are not felled by it of handshakes, kissing, hugs, the bodily frisson and common cause of everyday life, turning friends and lovers into risk factors, and strangers into vectors of the apocalypse. A few months ago a dear friend’s father, whom she used to visit weekly in a nursing home dementia unit, was diagnosed one day and died the next, and the sight of my friend, virtually alone in a blustery Massachusetts cemetery, her fingertips touching the closed box in the back of the hearse that held her father, was one of the most wrenching sights I’ve seen in my lifetime. Two attendees besides the funeral director at the burial. Our aloneness laid bare, bare—

It was a scene that begged an artist to find small redemption in its humbling dignity. At other times when our purchase on life has suddenly become precarious—during the Black Death, the 1918 flu, the holocaust, the AIDS crisis, say—artists have sought to offer metaphors, a way of shaping our collective understanding of the virulently incomprehensible. In the late Middle Ages, as Black Death swept across Europe and Asia, apocalyptic iconography adorned pulpits, illustrated manuscripts, mosaics and the like. In the pandemic’s earliest stages, the imagery tended toward the punitive, pestilence as an instrument of god’s clearinghouse. Anonymous sinners were cast into fiery pits, decomposing bodies set upon by jowl-licking dogs. Only toward the later stages, with millions already dead (many of whom may have been assumed to be non-sinners) did the imagery become a little more sympathetic, the sufferers and suffering humanized, and the artists’ less obsessed with sending earthly sufferers off to eternal suffering in the afterlife. On the literary front, one of the most well-known books to come out of this period reconsidered the Black Death as an instrument of suffering but also pointed toward human commiseration as counter to human impotence. In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353), a group of young people on the run from the plague entertain each other in a country villa, telling tales that are alternately erotic, heroic and comic. Even in the super-saturatedly religious time, steeped in crippling apocalyptic mythology, the young protagonists sought to create a rich secular life outside familiar tropes of salvation or damnation, with hesitant ambivalence about the origins of “the death dealing pestilence, which, through the operations of heavenly bodies or of our own iniquitous dealings, [was] sent down upon mankind for our correction by the just wrath of God.…”

In our own times, global pandemics, widespread environmental catastrophe, mass unemployment, the shared psychic evisceration of 9/11, neverending racial injustice, a crisis of identity in an increasingly dystopian American scene, has introduced a psychic trauma that seems not far from that of Boccaccio’s protagonists. As a rule, we might feel detached from millennia-old religious beliefs, but as we look into the crystal ball of our collective future we see little reason to believe our terrestrial kingdom can be sustained, and grapple with more than metaphors of mass death. In certain circles, casual conversation turns, almost invariably, to end days, destruction of existing mores, a society facing mortal danger from a virus that invisibly taints the air we breathe, and, in this country, the political party of Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt and Eisenhower being held in thrall to a thuggish simpleton. A redo seems not only just, but gives hope of a future when saner gods might reign.

In the Seth Rogan buddy-cum-end-of-the-world comedy, This is the End (2013), the end in question comes at a party at James Franco’s house as Hollywood partygoers tumble into fiery pits or are sucked up in blue columns that seem to operate like pneumatic tubes used in nineteenth century department stores, leaving Seth, Franco and their buddies behind, self-quarantined in Franco’s modern Xanadu. Modernists with vague religious awareness, for the life of them they can’t quite put together a list of the deadly sins to sort out why they’ve been left behind, and like seventeenth century theologians debate the Holy Trinity and power of god, when Seth suddenly has a stoner epiphany: “I mean it’s like, its like the real apocalypse. It’s like the Book of Revelations. That means there’s a god, right? That there’s a god? I live my life as if there’s a god, but.… Who actually saw that coming—that there’s a god?”

End came out early in Barack Obama’s second term, before the advent of MeToo, but months after the murder of Trayvon Martin, at a time when cynicism and possibility seemed to be struggling for dominion at the edges of America’s ailing frontier. Seen from a much darker 2020, the lesson of End feels quaintly hopeful, decidedly non-Old Testament, non-Trumpian. Care for each other. Don’t be a douche. Maybe there’s a god. Having learned their lesson, the buddies ascend in the blue columns to a dance-party heaven that’s everything a man-child could wish for, certainly not a place, seven years after the movie came out, most of us would consider congruous to our age of racial reckoning and world pandemic, where we’re inclined to regard each other like stunned survivors.

What exactly is an apocalypse anyway? And, by the way, who gets to advance to the next level? As an idea it’s harder to pin down than Webster’s might let on, or we might think of it. The word, Greek in origin (ἀποκάλυψις, apokaluptein), literally means “uncover,” or “revelation,” and the promise of a new beginning. God would flush out an old fallen world and replace it with a new, improved version. Such thinking really started catching on around the time of the Babylonian exile (597 BC – 538 BCE) as captive Judaeans were deported to Babylon. Judaeans had good reason to wonder about god’s promise that their kingdom would last forever. How were they supposed to take god at his word when their kingdom was plundered, their citizens taken away in bonds? An explanation was needed. So if the apocalypse idea came out of what was essentially a contract dispute, and after several millennia of additional contract disputes, one might argue it now accounts for tent revivals, cosmology, dystopian novels, Decameron, reform movements, This is the End, and nowadays what feels like collective anxiety in the declining days of the American moment.

On a secular level—not just god’s—apocalypses have also been political, and known to operate as displays of power, separating deserving from the undeserving. Take America in 2020. Over the course of his White House lease the ostensible leader of the free world has been barely able to maintain a baseline imbecility. By any objective measure he’ll go down as the worst president in history. But—and here is the crux of god’s methods too— the strongman tactics Trump employs with such gloating glee create a state of perpetual terror about our collective hold on the world. This is the End could laugh at it, but here we are— At the instant of pandemic, and collective national self-examination on questions of race and gender equality, the ostensible leader of the free world wades through cleared streets like a third grade bully, incapable of even pantomiming facial expressions beyond scorn and self-congratulation. An apocalypse suits his agenda of wholesale moral and physical destruction. By “making America great again” (that “again” being, perhaps, the most potently loathsome dogwhistle in history of the republic), the ostensible leader of the free world evokes nostalgia for a past that seems to come from an old tv-show lot, with painted backdrops and eccentric old maids walking their cats. The past as the promised land. But it’s a past as the past never ever was, not even for a day. It’s a past created for the specific reason of eradicating the inconvenient present (as all presents are inconvenient).

Metaphorically, apocalypses, in secular or non-secular modes, have often functioned as an inversion of nostalgia. Or is it more accurate to say that nostalgia and apocalypses are corollaries? Maybe. Yes. Nostalgia looks backwards for some Acadian idyll; apocalypses look forward to wholesale destruction and the restoration of the kingdom. In Thomas Cole’s series of five paintings, The Course of Empire (1833-36), a great empire rises and crumbles, victim of moral corruption and environmental depletion. The narrative is simultaneously nostalgic and apocalyptic. It looks forward to the destroyed empire’s return to nature: looking forward in order to look backwards. Now Make America Great Again exploits a similar fabled-past trope, but, despite the Again, without pretense of any type of restoration. The Great Leader replaces old monuments with cold monuments to himself. He builds the world’s ugliest buildings. He orchestrates Nuremberg-style rallies, missing only a willing Leni Riefenstahl to bath him in light. He sports with nihilism, the dismantling of civilization, and could care less about the lessons of the fall of Rome, nor about the long-view compensations of Course of Empire’s return to nature. Even Tump’s nostalgia is a phony, a gyp.

Yet the question still comes to mind, does the old trope still have something to say in times of pandemic, rampant opioid abuse, global protest, collective uncertainty? Even the ancient Christian theologians in their time had gotten a little squishy on apocalyptic thinking: Augustinian eschatology conceded end days were coming, but Augustine himself (354-430) was more or less agnostic about the how or when part. God would take care of the details. Yet, yet, yet— Despite a general trend over the last several millennia in favor of secular humanism and the shucking of old superstitions, the notion of apocalypse still does manage to rattle and excite our post-Original Sin, post-Darwinian, post-Nietzschean, post-Einsteinian imaginations. In times of social distress, we can sense ourselves as kindred to ancient Judaeans, Augustinian Christians and seventeenth-century puritans, seeking agency in a world beyond our knowing. Before the end of the Second World War everyday use of the word apocalypse had been in steep decline, and had almost fallen into disuse altogether. But since 1945 its everyday usage has gone up almost a hundred percent. As a word, as a metaphor, it acknowledges our growing sense that our worst nightmares might not be nightmares. Burning rain forests, police shooting of unarmed African Americans, the coronavirus dead processed in body bags, resource depletion, the holocaust, the advent of the atomic bomb, with its revelatory graphic of skies lit up in flames, aren’t figments. Perhaps, repurposed for 2020, the metaphor is perfect expression for our dread of imminent annihilation, both our own and that of the planet we thought was guaranteed us. Given such outrages, can the kingdom ever be restored?

You might be interested in

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

John Murrell, prolific bandit on the old antebellum Natchez Trace, had a talent for masquerade.

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

Sojourning down American highways via thumb.

Imarvel now that I was able to get from my apartment door in Brooklyn to Pennsylvania or Maryland or West Virginia and back in one long weekend without spending a dime. In those days, if you were so inclined and willing to put up with a little discomfort—standing on a treeless road a couple hours, camping by a culvert—you could make it across the entire continent for the price of a couple sandwiches.

Being of an abstracted and pilgriming nature, I was inclined.

I started hitchhiking in college as a means of getting from one place to another for free, and picked up on it relatively quickly. Via hitchhiking, the journey between Amherst, Massachusetts, where I was going to school at the University of Massachusetts, and my parents’ house in suburban Boston, was about an hour and a half if you were having any luck, three or four otherwise. By nature, I was as inclined to wander the byways of the country by sticking out my thumb as I’d been inclined to explore neighboring streets and towns via bicycle as a child. Summers in college, I’d catch rides to a beach town on Cape Cod where a tantalizingly intemperate girlfriend was living, and provided more than ample stimulus to travel to her via any means available. These early hitchhiking forays were primarily utilitarian, insofar as I wanted see my girlfriend, but they advanced certain metaphysical aspirations. It’s an exaggeration to say that hitchhiking made me a writer, any more (or less) than the intemperate girlfriend did, but some evenings, standing by the side of a road as light drained from concrete skies, displaced by quavering halos of streetlamps, I grew accustomed to a certain solitary perspective and depended on a wandering mind to preserve a toehold on reality that may have fueled literary inclinations.

Hitchhiking provokes hallucinations: mirages, a sense of temporal fluidity, hovering in margins. If you’ve ever been stuck in a unknown town, transportationless, you’ll know what I mean. One realizes one belongs, metaphysically, only by provision. I remember once, after hitchhiking back from the Cape, walking down the street where my parents lived—about 3:30 in the morning, I guess: an indeterminate time of errant lovers, nightshift workers, long-distance commuters pulling out of driveways—and the doorbell buttons of three or four houses were glowing identically yellow, as if floating in a medium of clear jelly. It was an image that, for all its banality, made my throat clench. I remember staring, transfixed. Even here, on the overfamiliar street of my childhood, there was a quick thrill of exile that held me in thrall.

Historically speaking, it may be no accident that hitchhiking started in America. Maybe it’s our gift to civilization, along with jazz or superheroes. The notion that you could or ought to submit your fate to the goodwill of strangers harkens, perhaps, historically speaking, to a quainter version of American life. Let’s pick the nineteenth century, for sake of discussion. 1829’s a good year—with its mania for macadam road and canal building. The Erie Canal is nearly complete. Andrew Jackson sits in the Executive Mansion, promoting internal improvements. But railroads have yet to proliferate. To get from Utica to Albany, you can hop a flatboat, and find yourself there in ten hours. In Mississippi, a wayfarer dropped at a levy landing might start hiking with his satchel, and in the afternoon knock on a stranger’s door—the expectation being he could get a cot for the night, a rude breakfast in the morning. Perhaps the wayfarer offers some sort of payment, or the host holds out his hand for it. Or not. But such was the temporary, transactional, improvisational nature of these early alliances. Doubtless transactions could be fraught, strangers turned away, robbed of their possessions. Bands of highwaymen did, after all, prey on peddlers and travelers along the Natchez Trace between Nashville and Natchez…. But travelers, in general, depended upon predictable outcomes, and acted in accordance with this premise. Highwaymen be damned.

A couple decades later, traveling in the deep south before he became a landscape architect, and reporting for the New York Times on the lore and folkways of what amounted to a foreign people, Frederick Law Olmsted complained of the mean hospitality offered by supposedly hospitable Southerners. “We slept in all our clothes, including overcoats, hats and boots, and covered entirely with blankets,” he grumbled, “and after going through with the fry, coffee and pone again, and paying one dollar each for the entertainment of ourselves and our horses, we continued our journey.” Sleeping in stage stops, haylofts, spare cots, crossing rivers on private ferries, Olmsted relied on informal linkages, improvisation. But his complaints about poor blankets and pone strike me as slightly ungrateful, as if a hitchhiker were to gripe that every car that passed didn’t pick him up, or a driver in one that did might not tell fascinating stories. Imagine knocking on a stranger’s door in 2018, looking for a cot and a meal. In 1857, no backwoods farmer was under obligation to take in a probably pretty disheveled Yankee, but even in the backwards antebellum South, a wayfaring stranger (a white stranger…) wouldn’t go bedless or unfed for the night.

In 1900, about 8000 cars were registered in the US. Twelve years later there were 901,596, and the American troubadour poet, Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, could write: “When the weather is good, touring automobiles whiz past…. About five o’clock in the evening some man making a local trip is apt to come along alone…. He will offer me a ride and spin me along from five to twenty-five miles before supper.” By 1917, when the US entered the Great War, precisely 4,727,468 cars cruised the American roads, and car culture as we understand it today was well underway. By many accounts, hitchhiking (insofar as the term applies specifically to petitioners of automobiles) proliferated around the army training camps around the country. In such population centers—Camp Devens, Fort Slocum and Camp Funston—word spread quickly: doughboys on leave could hitch rides home for the weekend, visit girlfriends far afield, possibilities that must have seemed fantastical to boys who’d never been farther from home than they could travel by horse in a day, as Faulkner said of the young soldiers in the Confederacy. By the time the movie, It Happened One Night, came out in 1934, hitchhiking was common enough that a driver who stopped to pick up Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert recommended it for honeymooners. “If I was young, that’s the way I’d spend my honeymoon. Hitchhiking.”

In my own period of wandering and hitchhiking, I took buses, flew, hopped freight trains, bicycled, crisscrossing the continent from New England to Kansas, Texas, the Yukon, Alaska, the Deep South, not aimlessly, but with no specified agenda in mind other than to take in impressions, see how people lived, and what the places they lived in were like and what their faces were like. Despite my pilgriming nature (maybe that’s not exactly right—), I wasn’t on a quest, but rather, I suppose, I was hoping to experience life in a wide gyre, and live as fully as budget and tolerance for an ascetic existence could sustain. As a kid, I used to share a back seat of a station wagon with my siblings as the family drove across the country (my father was a junior high school principal, and had summers off), and, though I was more likely to read than gander, I suppose I absorbed something of the country’s history and geographical extent by osmosis, taking in clouds over the Rockies, the lullaby of tires on pavement…. Trips forever associated with long highways going I wasn’t sure where.

I’d been warned, of course, of the perils—strangers who’d take your things and leave you on the side of a road. The warnings, coming from parents and others seemed unrelated, for the most part, to experiences I had. There were some unpleasant episodes here and there. Once when I hopped into the cab of a snorting eighteen-wheeler, the driver, a bluff, ruminative man, began to point out the exquisite comfort of wearing women’s underwear on long hauls, and urged me to try the same. He didn’t press himself on me, but cheerily tried to coerce me into changing there in the cab. One night, outside a city in Arizona, a man seemed to mistake me for his son, lamenting the son’s loss (I was unclear what he meant—) while massaging my thigh. In Georgia, I was once left, precisely as warned, at a gas station as the two yahoos I’d been riding with for hours drove away with my backpack, which contained my wallet, clothes, precious books, what amounted to everything I possessed at the time. But these incidents, however sordid and discomforting, were not exemplary. Oftener than not, the driver would belong to the class of middle-aged, mildly disappointed men in thankless marriages, with crap jobs, overextended credit, equipped for survival by the barest skim of self-reliance, but kind enough to pull over for a stranger. They shared, almost universally, stories otherwise backlogged, about affairs, lost sons, sad denouements, secure in the fact that they’d never see me again. Like a descendant of Nick Caraway in Gatsby, I was subjecting myself to the secret griefs of desperate men, but I listened. I honed a talent for listening, sometimes into the night, with the low murmur of a radio for accompaniment, and the hushed attention of the stars.

Hitchhiking must have peaked as an unstigmatized means of getting around sometime in the 60s or 70s, lingering past the Merry Prankster, Haight Ashbury, Woodstock eras, and hanging on into the disco or later. The weekend on-leave excursions of the Great War doughboys layered not altogether clumsily onto the sojourns of hippies and freelance adventurers: doughboys, by way of Vachel Lindsay, updated as free-spirited hippie girls with wind in their hair. But at its peak hitchhiking was already perceived as something subversive and dangerous. In 1968, Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys picked up a couple free-spirited girls, who happened to be Charles Manson followers. Within a few days Manson himself and the girls moved into Dennis’s Malibu house. They were there two months before Dennis finally got creeped out, and kicked the ensemble out. It was no longer just doughboys or hippies or honeymooners or Beat Generation hepcats on the road, but a dangerous element exfoliating Americans’ belief in themselves. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) may be one of the most celebratory, even patriotic novels of the 20th century, but it’s self-consciously premised upon the trope of outsider as patriot (a trope that usually works best if you’re in the in-group). Take a look at photos from the 50s and 60s—it’s mostly not Beat poets and hippies, but the suit-and-tie types scratching their heads at the non-conformists. Despite jazz clubs, the Further Bus, Woodstock, the Stonewall riots, the Beats’ and hippies’ revolutions eventually collapsed under the impossible burden of utopianism, their radicalism shrunken and commodified: the counterculture pressed against the barriers but never really broke through.

The publicity surrounding the Manson murders (a year after Dennis Wilson picked up the girls) may not have spelled the absolute end of hitchhiking, but it was around that time that signs posted on the roadsides warned of dangerous freeloaders, ex-cons, lechers, undesirables. The Interstate system (an Eisenhower-era scheme completed, more or less, thirty years later) institutionalized the prohibition of hitchhikers. By 1986, as the coast-to- coast Interstate (I-80) was completed, there were 126,425,301 cars on the road. Roughly 7.5 for every 10 citizens. Essentially, a state drivers license was a national ID card. Vehicle ownership was tantamount to citizenship.

So the comparatively brief ferment of 60s Samaritanism may have proved unscalable, but it also proposed an ongoing interrogation of middle-class American cushiness. It hardly needs saying, but I’ll say it anyway: our national optimism has always had a narcissistic side that claimed America as the Promised Land. The guardians of mainstream culture (self-appointed or otherwise) take it upon themselves to keep out the undesirables (from Catholics, Germans, Chinese in the 19th century, to Jack Kerouac, or Mexican “rapists” at the border). If hitchhikers too were eventually cleared from the road in the name of decency and conformity (a hitchhiker on the side of a road in 2019 is as rare as an Ivory- billed Woodpecker) then it seemed part of a general repudiation of Woodstock-style upheaval. Outwardly, the end of hitchhiking was a small extinction, perhaps, but small extinctions take down ecosystems. Hitchhiking had always been an experiment of democracy, a spontaneous test of our trust in one another, and its demise took with it some of that trust, or the other way around.

One morning, toward the end of my hitchhiking days, I was half-heartedly walking through a hamlet in Missouri, holding out a sign. A car pulled over. I thought a voice called my name—an impossible idea. I didn’t know a soul within a thousand miles of wherever I was. Another hallucination, the product of long stretches of standing beside hectic highways— The driver, dark haired, early twenties, introduced himself. Then asked if I was who he thought I was. What could I say? I looked at him. Nothing computed. Sometimes even simple facts, expressed without adornment, throw you into madness.

Here’s the short version: three years earlier I’d had a conversation with a family at a campground in western Montana, part of a missionary group caravanning to Wasilla, Alaska, up the Alcan Highway. They invited me to visit Wasilla were I ever to make it there. In fact I did—several months later. I had a brief dinner with the group and left the next day, taking the ferry from Haines, on the panhandle, to the Lower 48. Three years later, the person who pulled his car over in Missouri recognized me as the person from the campground and the dinner. He’d been a member of the missionary family, a teenager then. When he saw me, he was sure enough that I was the same guy that he called to me by name. People run into people they know all the time at St Mark’s Basilica, Time’s Square, the footwear collection at the Smithsonian, and call it coincidence. A sceptic might have a point in calling coincidences nothing more than fictions appearing to organize into natural order, making secular religion of nothingness. But this— To encounter this guy on the side of the road in a town in Missouri, population 15,000 (I’m guessing), tends to make one believe in guiding forces, and wonder at the drollness of fate.

I got in, we talked inconclusively for a while, as if we ought to make something of the happenstance but didn’t know how to go about it. I should come for dinner, he said. Meet his wife. Thank you but I was in a rush, I told him not untruthfully; not too far down the road I got out of his car, and shook his hand through the window. It felt both meaningful and very inadequate. What’s there to say on such occasions? We knew each other only as unwitting associates in a singularly unlikely episode; characters in someone else’s narrative. I walked along with my backpack and sign, consciousness of being gobsmacked. A little wind picked up, if I remember, an unremarkable bit of weather that seemed obliged to a particular place, that couldn’t be reproduced in any other. I was on my way to Boston, grad school. I was coming to the end of hitchhiking too.

You might be interested in

Between 1974 and 1976 Patricia Hearst, UC Berkeley student, scion of the prominent California Hearsts, became the most wanted fugitive

A brief history of being young & adrift in 80s New York.

Bonnie Parker was nineteen years old and been married four years when she met Clyde Barrow in the winter of

Reconsidering the supreme stylist's status in the canon.

The Klan in my backyard.

Childhood is the entertainment of the improbability of an ending, plus an ongoing instability of the moment. When I was a boy growing up in Sudbury, Massachusetts, at five, six, seven, I believed, probably like lots of kids that age, in the commonplace of the miraculous, the likelihood of coincidence, the inevitability of imaginative truth. That’s to say, if I composed a letter from an ostensible pirate in blood-mimicking red ink, complete with treasure map, such a pirate must indeed have existed, swashbuckling through my backyard in some distant epoch. If a time machine could be conjured out of twigs and old cereal boxes, I was, voila, transported to some Civil War battlefield, or reassuringly tragic Viking langskip. A bliss of free association prevailed.

In this once-agricultural now suburbanized colony of Boston, childhood was good. Or anyway, on the little side street we lived on there wasn’t a lot of cultural data to agitate for a conflicting perspective. It was the Sixties in high season, and the anti-war protests, the Freedom Summer, the blown-up churches, the dead kids, the assassinations, Woodstock were in full bloom, yet the Sixties as historical moment occupied only the extreme periphery of my childhood attention, and, as far as I could tell, the attention of the adults around me. Only glimpses of Time magazine pictures of Martin Luther King, My Lai, or the novel wardrobe choice of a formerly orthodox mother, hinted at the world at large. We were—the Cards, our Eddy Street neighbors, the neighborhood kids—safely, homogeneously, white, mainly anglo, aspirantly middle-class. To the kids of young parents—my peers—the draft was hypothetical. The violence gutting the American South might as well have been taking place in Timbuktu. Woodstock—it was something a friend’s uncle had come back from with a different girl than he’d gone with.

Neither did history make much of a dent. A decade or so after the Second World War, in a second spasm of Levittown-like development, the cheap uniformly neocolonial houses of Eddy Street had been thrown up on the site of a plowed-over farm and apple orchard. A busy thoroughfare—Landham Road—connected Sudbury to Saxonville, a rather desultory collection of brick mill buildings that had seen better days. But the traffic effectively cut us off from the wider world. Eddy Street denizens seemed to be claimants of an obscure, freshly buried and irrelevant past, isolated like an Amazonian tribe that has lived for hundreds of years next to another but never known of its existence. The blissful backyard lawns, having been bulldozed of trees, blended seamlessly into a singularly blissfully unbroken suburban desert as far as you could see.

Oddly, such an a-historicized landscape also managed to yield more than its share of precious semi-historical artifacts. Over the years I stumbled across oxen yokes, a Conestoga wagon wreck, hulks of old cars in the scant surviving woods behind our house. Incidentally, our yard also contained a geological oddity that seemed part of an even more ancient past: a hundred yards back from our house, where the Eddy Street development had been stopped at the town border, was a natural amphitheater, banked with high steep slopes, and enclosing a small flat patch of land. The grove we called it. Sometimes we boys flung ourselves from the grove’s sloping banks, seeking, one reckons, a token of desire to exist out of bounds.

One day we heard on the radio—there was always a radio in those days—that a prisoner had escaped from a nearby prison and possibly been spotted in our neighborhood. We kids were all told to stay indoors. Hoping to get a glimpse of him—a guy I imagined wearing a striped uniform who’d be sufficiently menacing to make looking worth the risk—I peered out between a gap in the dining room curtains. Maybe I even opened the side door and stepped out of the porch, electricity jolting my nerves. Who knows?

Eventually, I suppose, he must have been apprehended without a shootout or a chase. I didn’t hear anything on the radio anyway, or from my parents, or if I did hear about the moment it didn’t register with enough jolt for me to remember it now. In any case I never got to set eyes on the guy. The narrative was a bust.

Summers passed. We kids (even our names spoke of a certain freebooting exuberance: Chuckie, Dean, Bib, Dickie…) roved the neighborhood unimpeded by phantom escaped prisoners. We made up our own games and dramas with an assumed proprietorship—in ragtag parades, clothed in garb of Korean war veteran fathers, or in paper bags that we drew on to make up our madcap finery. We were knights, soldiers, and rightful claimants to Eddy Street’s obscurer precincts. One summer we formed a regiment to give battle to regiments from nearby houses. We patrolled Eddy Street on our bicycles (my Schwinn Lemon Peeler, modified with a glowing skull figurehead, being the pinnacle of chopper aesthetic), and swung gigantic tree branches at one another until we collapsed, our bodies depleted. Untethered from adult oversight, we were free agents, feral roving bands.

Let’s just say it. There’s something almost invigorating, almost subversive, about homogeneity of enterprise. I don’t mean this in a nativist/ignorance of outside influence way. I mean it, perhaps, in a knowing of the self as an infinitely variable commodity way, and locating that self in a culture that bolsters it, even in the short term. Of course, culture’s malleable, unruly, unreliable. Of course. One’s place in any culture conditional. But, looking back, it seemed for a moment that for all its blandish pleasures my brief Eddy Street tenure had come at a particularly harmonious time and place, and that its effects were longer lasting than I could have ever anticipated.

But what really prompted the writing of this little essay wasn’t directly related to my childhood at all. It’s something that happened in the neighborhood almost forty years before I was born, and was relayed to me decades after I lived there.

On a warm summer evening in the late summer of 1925, a group of local men, and more than a few from nearby towns—possibly two hundred in all, two-fifty—gathered at a farmhouse on the property my family would own some forty years later. In my imagining, there’s a fine mottled sky, fireflies, clouds, an ambient buzz of mosquitoes, Model T’s looking for parking. The cops were out, state as well as local. The owner of the property, a Spanish-American War veteran and farmer, F W (Perley) Libbey, is a figure obscurely infamous, mostly lost in history’s churning. But one can picture him, as I do, middle-aged, lean with hard labor of farming, suspicious of anyone outside his orbit in way that seems perfectly contemporary. On the night of the gathering, he’s rushing about, making sure cars don’t park in the fields, glad-handing guests, chuckling with the cops and locals about the more-than-expected turn-out, and the possibility of trouble.

Libbey was no innocent, no dupe. A few weeks earlier, he’d been arrested for wielding an unregistered gun at a KKK rally in Westwood, Massachusetts. Klan rallies had been held at his farm earlier that summer, threats made to Catholics, Jews, newly arrived eastern European immigrants. He was up to his ears in vindictiveness. On the night of the rally in what was to be my backyard—probably the grove, bound by the slopes I loved to tumble down—men in the vestments of the KKK were waving placards, flags, burning crosses, their chanting the unregenerate gibberish of those assured of their righteousness.

By six o’clock, the Model T’s, Nash coupes, Durant sedans, were lined all up and down Landham Road (the busy road that we kids would one day be forbidden to cross), it was nearly impossible to get through the phalanx. Latecomers were getting out, walking half a mile. They carried an assortment of clubs, shotguns, pistols, American flags, placards, as if readying for patriotic display. Some came wearing overalls, or suits and neckties of the era, stubs of ties slapping over bellies. Many—most—were wearing white robes, hoods pulled off to let the heat out, and in the mellowing light you could see their faces, reddened, their mouths slackly breathing moist unmoving air.

New group members looked around, seeing where they fit in. Greetings were extended— crushing handshakes. How could they help. Indoors, two or three women cooked pies in a coal oven. All these men were going to be hungry. The lull was proving itself to be comfortable. A few protestors, the Irish, the Italians from Saxonville, where flourishing carpet-weaving mills attracted low-wage workers, were hanging around by the asparagus patch, but not like it was in Westwood.

Pop culture between-wars pre-Depression America came on as modern, uptown, flapper- in-the fountain, jazz-mad pastiche, boardwalk beauty contests, T J Eckleburg, Harlem…. But pockets—nay, great swaths—of America lighted their houses with kerosene (the Libbey farmhouse could have been one), got its news from Readers Digest, and workaday life might seem hardly different from life under, say, the administration of Martin Van Buren. Boys had tramped off to war on the Continent in 1917, presumably returning with visions of Parisian footlights as well as the trenches, but there’s endemically stubborn provinciality in American life—a nasty flip side of our myth- aspiring individualism. Did a couple weeks leave in Paris matter when you returned to the homestead and had to start digging ditches, and an Irishman or Armenian had moved in next door? Even during the War, when black soldiers (in segregated regiments) beat back the Germans in the Argonne Forest, provinciality at home never stopped flirting with terrorizing racism. D W Griffith’s bogus epic of a film, Birth of a Nation (1915), idolized the original Klan, and soon after its release a resurgent second-wave Klan expanded the mission with an anti-Catholic, anti-Jew, anti-Italian, anti-pretty-much- everything-not-born-on-the-Mayflower agenda. All over the South, Midwest, Northeast, the new Klan stepped up its intimidation efforts, like a boosterish Kiwanis club with race war on its mind.

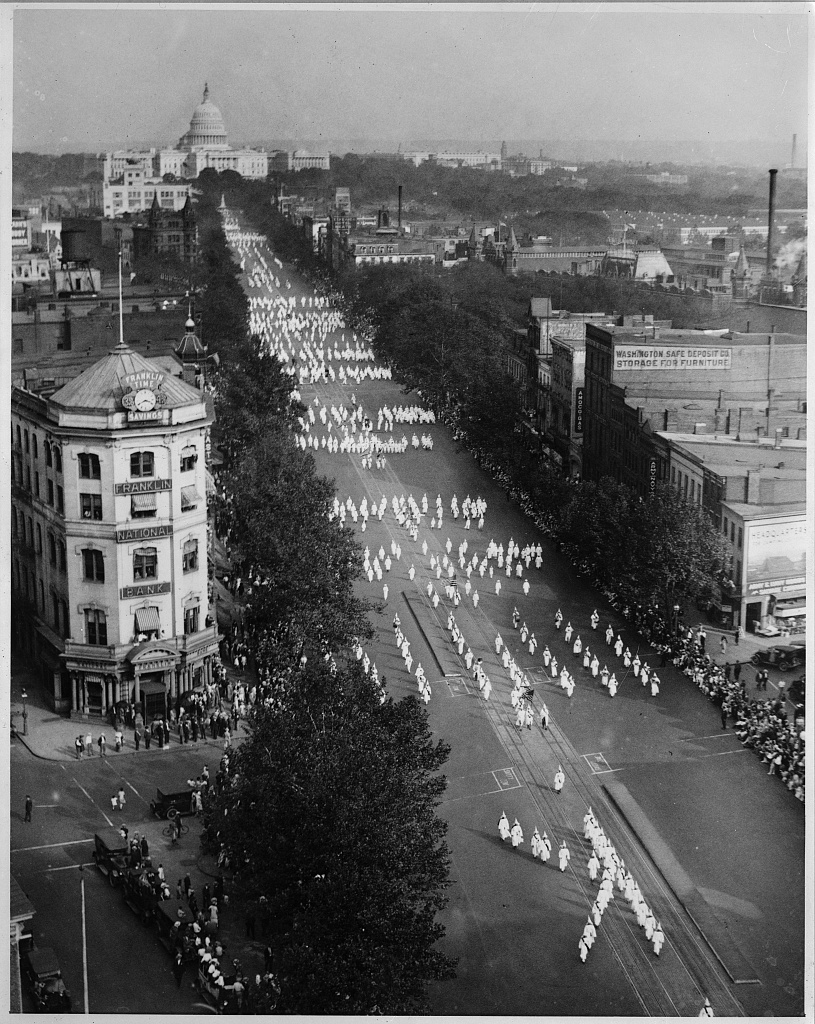

One only has to follow the segregationist folly of Know-Nothingism to Jim Crow to the Immigration Act (1924) to get a pretty clear picture: the Klan was just a silly costumed manifestation. The original Klan had topped out at a hundred thousand or so members, mostly ex- Confederate freelancers trying to fend off Reconstruction and hold onto a slippery white hegemony. But by 1925—the peak of the second Klan’s cultural saturation—the Klan could muster, nationally, some four million members, give or take a few million. In Massachusetts alone there were estimated to be 80,000 hooded costumes ($6.50 each) hanging in the backs of closets of farmers, merchants, ministers, police captains, bankers, undertakers, teamsters, shop clerks.

Nineteen-twenty-five may have been a pretty slow year for lynching—only seventeen African Americans were tortured, hanged, mutilated—but just a few days before the events at Libbey farm, some 40,000 Klansmen paraded through the streets of Washington DC, singing, jabbing the air with their signs, marching in formations of crosses and the letter K, demonstrating the Klan’s power in the very heart of the democratic experiment. And it was in this superheated atmosphere that immigrants, mostly first generation, some Irish, Italians, came ambling over the hill from Saxonville, down dirt-paved Landham Road, confronting the armed and riled-up Klan at the Libbey farm.

It’s impossible to piece together exactly how things started, but maybe not hard to piece together how it accelerated. Feeling an advantage in numbers, protestors pressed on the farmhouse, barn and chicken coop; Klan members, feeling cagy, telephoned for reinforcements and got through to some guys getting off the shoe factory late shift, maybe an accountant or who’d already turned in for the night. In the next hour or so, additional men—twenty, thirty—were coming down Landham Road from the north, beating their way through the protestors. By this time it must have been 11:30, 11:45.

Names were called, let’s say. Papist. Shit-for-brains. Stronzo. Someone bent down to pick up a rock. Someone hurled a piece of an oxen shoe. A Klansman was hit in the shoulder. On the side of the head… a broken nose gushed blood and snot. The cops were doing their best, but they’re they’re human, they’re not trained for this. A furniture store clerk—maybe he’s a kid, twenty-three—waved a rifle out the chicken coop window.

Everyone around him started clamoring, taunting, then you can’t do anything but shoot, can you. Maybe he doesn’t even remember after a while. One of the Irish spun around, crimson pooling in his shirt. It was on his face, blood everywhere. The guy was just standing there, like he forgot something at the store. Now other guys started firing into the crowd, and protestors, trampling over each other to get out of range, were shouting, sobbing, cursing, lobbing back rocks.

Five protestors were left behind, binding their wounds with their fingers, licking blood. William Bradley. Frank Maguire. Edmund Purcell. Thomas Sliney. Hit with buckshot. 22. Also Alonzo Foley. The guy who hadn’t moved. Alonzo crumbled to his knees now, holding his head with a cocky grin, his eyes fluttering. Twitching. A priest, youngish, soft-handed, his hair tight to the scalp, murmured last rites, giving the sign of the cross. After a while the others got taken off in Saxonville taxis, to a doctor presumably sympathetic. Alonzo went in the back of a four door sedan. Now it was probably around one o’clock in the morning. Maybe later. Kids hanging on the edge of Landham, losing interest. Dogs pacing up and down. State Police, motorcycle cops spread out over the asparagus fields, the orchard, and chicken coup, rounding up Klan guys, Sudbury guys— Curley Libby, Robert Atkinson, Ralph Chamberlain, Oliver E. Ames, Harry Rice—some of whose names are on municipal buildings these days. Guys from Waltham, Needham, Newton, Wellesley. The son of the police chief got scooped up. Light was starting up over the trees, ragged, unconvinced. Nash roadsters, Model T’s paused, trying to get through, the drivers squinting through smudged spectacles on their way to work. A couple half-eaten pies were strewn across the farmhouse kitchen floor, the Klan women raking up the mess with forks and dustpan. Alonzo was supposed to die in the middle of Landham Road, buckshot to his temple. But the fact is he didn’t. He lived until well after my family and I moved away. In 1979, at age 87, Alonzo died. I was on to other things by then, pursuing my own academic and literary aspirations, leaving Eddy Street far behind, I hoped.

Nineteen-twenty-five had proved to be the high water mark for this version of the Klan. The march on DC was the largest assembly it would ever muster. By the 30s, wracked by scandals, internal corruption, and external resistance to its vision of a racially, morally unanimous America, the Klan shrank to a few thousand members, persisting only in isolated chapters throughout the country. The respectable attorneys, bakers, mechanics, farmers, returned to harboring their grievances in less civically boosterish ways, or modified them in accommodation of a world that wouldn’t cooperate with their mania for purity. By the time my parents purchased their Eddy Street plot, I could live in relative obliviousness of the events of forty years earlier, free to cruise on the Lemon Peeler over land where old Libbey had meant to make his stand. Only, like some virulent strain of bacteria, the Klan did reconstitute itself in the civil rights crisis of the late sixties, at the time Libbey himself had gone to his grave (1965). A virtual protectorate of the intrenched Southern political power structure, it renewed its commitment to subjugation through night-riding vigilantism, murder, terrorism.

America tilts to the affirming word, the frisson of possibility, a kid riding a bike. But it’s reminding you. Always.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

Compulsory patriotism:

The National Anthem as sports ritual

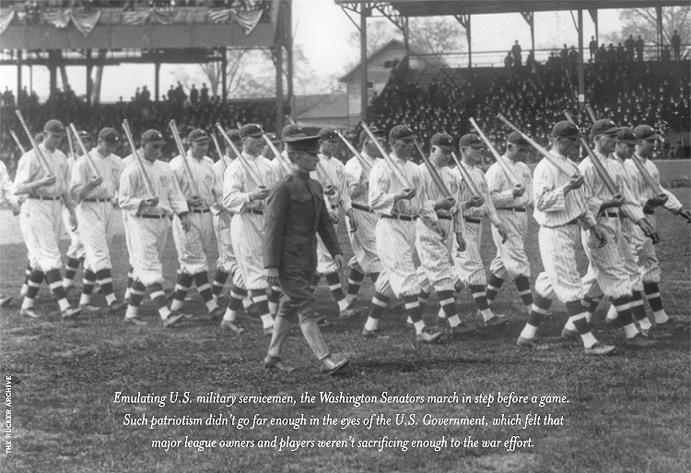

In the summer of 1918, baseball’s relatively early days, before the game became so self- consciously uppity about being a national pastime and all, you’d see doughboys about to be shipped off to Ypres and the Ardennes (including lots of young men who a few weeks before had been wearing the uniforms of ball players) parading in formation onto Shibe Field, the Polo Grounds, Ebbets etc. Players in team uniforms shouldering bats like trench guns. And martial displays like this were often accompanied by brass bands playing popular songs of the day (Ostrich Walk, Over There, It’s a Long Way to Tipperary), jaunty performances that inculcated fans with a sense of catchy good cheer. On occasion a band’s repertoire might include America the Beautiful or My Country Tis of Thee, stirring a not-so-latent sing-along patriotism in the grandstands. But in the first game of the World Series that year, during the seventh inning stretch, a band struck up an old drinking and whoring tune, now reconfigured by Francis Scott Key via John Phillips Sousa as the Star Spangled Banner. The stretch had been around in one form or another for a couple decades, its origins lost in tobacco-stained mythos of Wee Willie Keeler and Charlie Buffington days, but the Anthem had been played only sporadically before this. In 1918 it hit the zeitgeist in the gut. The Spanish flu pandemic was killing hundreds of thousands, the Great War churning on with no end in sight. Anarchist bombs were going off in American streets. Emotions were pitched. Some Red Sox and Cubs players saluted the flag or, hands over hearts, lustily sang along with the band. A few spectators wept openly. Also, don’t forget the Anthem hadn’t yet been encumbered and enhanced by a million emotionally overcharged renditions at every county fair and Super Bowl, but its yearning for familial reunion seemed to align with growing national communalism, conjuring friends, lovers, husbands, brothers half a world away. By 1919, the Star Spangled Banner was off and running. It was already the de facto official song of baseball, a sacred yin to the secular yang of Take Me Out to the Ballgame.

Anyone who’s ever been to a ballgame knows there’s something lovely, sublime even, in massed decidedly amateur voices belting out the Anthem into a ballpark’s vast green spaces. But such displays also scold. As with lots of facets of American life, patriotism in early baseball ordinated rather unhappily with congregational piety. Stadiums full of people singing together tended to veto the dissent of those who weren’t so ready to get with the program, or weren’t even invited to the program in the first place. 1918—year of the Dillingham-Hardwick Act—rooted out communists, labor organizers, anarchists, and shipped them back to from whence they came (eastern Europe, presumably). A few years earlier the movie Birth of a Nation had rebooted the Klan franchise, generating waves of anti-Catholic, anti-Black, anti-Jewish sentiment across the country. Baseball’s uptake of patriotic displays into the game’s custom and lore assumed political, racial, behavioral conformity. It assumed some valence of martial righteousness along with the shared sentiment.

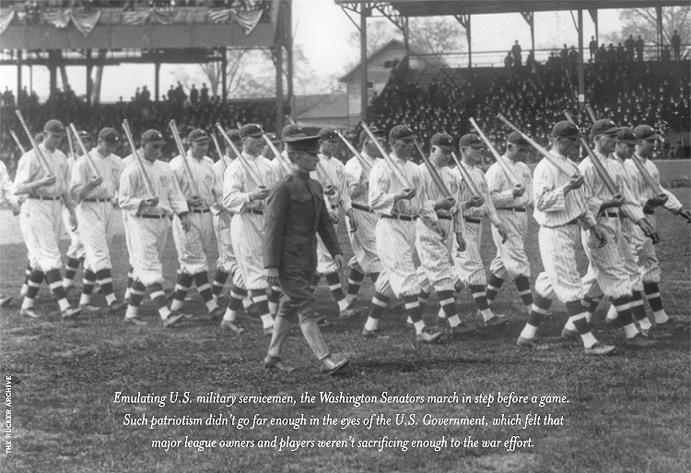

When Shoeless Joe Jackson, uneducated and arguably the preeminent pure hitter of the era, tried to get around the draft by registering as an “essential worker” at a shipbuilding yard, fans and the press went after him, labeling him a draft dodger, a traitor and, implicitly, unpatriotic, a pinko. Imagine—the gall of not wanting to die in a haze of chlorine gas, or machine gunned in snarl of barbed wire in a war of global madness.

One genuinely wonders about the nexus of sports and national boosterism in the first place. Do games, inherently, constitute a patriotic exercise any more than doing the dishes? Maybe they do. Games as performance pieces, heeding national interests, played over and over again as variations on the martial theme? Maybe— OK— But from the earliest days of professional sports, the moral imperatives were hard to separate from the financial, and from corporate manipulation of sentiment. Not only were customers— good, paying customers—sneaking away from the office to be treated to the spectacle of young men batting and catching balls, but with a little moral uplift might these customers come a lot more often? Marching bands, the Anthem, soldiers, recruiting booths, elevated the ballpark experience to that of sacred national ritual. Owners got it—the way owners understand the bobblehead.

Next year, with the Great War having ground to an end, and the country in a mood for returning to peacetime routines—and Shoeless Joe back on the White Sox—the Star Spangle Banner was routinely played in the parks, a de facto anthem for American unity (or some version of unity: baseball grandstands in 1918 were places for men in bowlers and boaters, factory workers, office workers, gamblers, swells, family men—white men).

What was being sold, subliminally, was a storied tradition of patriotism as martial covenant. Patriotism and war may not be entirely synonymous in this country, it’s true, but let’s face it—our origins are in the violent overthrow of paternalistic shackles, the righteous and viscerally horrific upheaval that was the American Revolution. Wave a flag—you’re acknowledging the collective memory of the Revolution. And possibly elevating the pastoral version of the story to the status of myth. Hold hand over hearts, have a beer, root for our home team in the August sun…. What’s the net effect?

The Anthem’s lyrics remind us:

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming… And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave….

Chronicling an obscure battle in an obscure war, the words call us to acclaim all that gleaming and streaming. But our vantage—Francis Scott Key was eight miles from Fort McHenry—is pretty limited. The blood and mire, gruesomely shattered bodies, aren’t visible, even by the rocket’s red glare.

Building a nation, as it happens, is rife with tar-and-feathering, finger wagging, idealistic, philosophical, intellectual thrashing about, battle scars, young men dumped in shallow graves, stubbed-out butts of utopian dreams. But from the perspective of a pastorally green ballfield on summer’s day, the grimmer aspects appear rather hazy. Even in the grandstand’s more urbanized welter of cigar smoke and spilled beer and body odor, you accept a folksy Spirit of 76 version of patriotic gumption.

By the time the US entered the Second World War, baseball had established itself as the national pastime without peer in professional sport. The NFL, in a protracted fledgling phase, lagged far behind college football in popularity. The six team pro hockey league was small potatoes, and Canadian to boot; makeshift basketball leagues and barnstorming teams came and went in middling industrial cities without leaving a trace. As the quasi- official game, in part by default, baseball lived with all the symbolic burdens that entailed, and was tacitly entitled to its share of national prerogatives. Presidents from Taft to FDR had thrown out the first pitch of the season. In early 42, FDR wrote a letter to the magisterially named Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, explaining “I honesty feel it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.… These players are a definite recreational asset to… their fellow citizens. And that in my judgment is thoroughly worthwhile.” A fine line that eventually introduced young teens, one-armed outfielders and wooden-legged pitchers to the majors to keep the game going (though integration as a means of filling the ranks was barely considered). The day after Pearl Harbor, Bob Feller, the Cleveland Indians pitcher who’d dominated the league as a seventeen year old in 1936, famously drove down to his local Navy recruitment office and hitched up. Players weren’t exempt from selective service, Roosevelt told Landis, but lots of high-rent players like Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Stan Musial, though officially enrolled, played out the 42 season. Williams eventually became an ace flier. DiMaggio, Musial and others, protected by their status in a way that lesser gods were not, spent their time sunning in California, Hawaii, playing exhibition games, demigods in palmy exile. At home, between games of a doubleheader, Babe Ruth—creaky and bloated from hotdogs, beer and retirement, slow to get around on the nickel curve—pulled on an old number 3 uniform and, taking swings against the Big Train (Senators totem Walter Johnson), raised money for Army-Navy relief. As newsprint sloshed with rolls of the dead, the Anthem was played at every home game, as salutary as it was compulsory.

Putting aside the slightly inconvenient reality that the alliance that beat the Nazis included a country ruled by one of the greatest mass murderers in the history of the modern world, you might agree that the eventual allied victory evoked the clearest moral triumph of good over evil in the history of the modern world. And the country had every right to feel upright. If, incidentally, the war also incited faith in the hegemony of industrial capitalism, of tanks and Jeeps and battleships and American bomb building know-how—the smug chauvinism of moral rectitude that comes from discovering one’s nation wielding the closest thing to absolute power a country has ever known—that was the price of admission. Professional sports wasn’t slow to take up the cry either. The strain of intolerance of the Great War was blooming into post WWII boosterism. Tail Gunner Joe rising. By 1942, most baseball teams played the Anthem before the game.

Upping the ante, the NFL mandated in 1945 it be played for every team for every game.

“The playing of the national anthem should be as much a part of every game as the kickoff,” wrote Commissioner Elmer Layden.

Nowadays at pro football games, a PA announcer with a voice like a third world

generalissimo’s decrees the crowd remove hats, place hands over hearts, salute, genuflect, sit. Absent exercising any deeply felt patriotic impulse to read the collected works of P T Barnum, you reflexively follow instructions, heedless of their high kitsch. The veterans of Iran or Afghanistan in clean uniforms and gleaming medals come onto a field and wave to the crowd, cameras zooming in on their faces, symbols of they know not what. Do they ever wonder if they are being used, trotted out, wadded up, tossed away? Are they disoriented, dumfounded by schisms in their experience? The thing they’re supposed to be celebrated for devalued by the very celebration? For the fan, try sitting in your seat, drinking your beer, thinking of Antietam, Daniel Shays, Jackie Robinson, you look like a jerk, an ingrate, indifferent to the blessings of a country that’s mostly tried to live up to its high ideals. But could it be the opposite? That one can care deeply about one’s country, and shun the hireling ordering you to put your hand on your heart (a tradition, by the way, stared in 42, along with recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in school).

Colin Kaepernick takes a knee. Colin Kaepernick does not salute. Colin Kaepernick has hair like terrestrial tumult. This is history quivering with meaning, giving off inventories of vibrations. You don’t even have to agree with what Colin Kaepernick’s saying to grasp it. It’s perhaps the most genuinely patriotic answer to the Anthem’s real plea. Such allegiances are liberated from common pietism: protesting America is the precisest expression of Americanism. Not the faux of entitlement, narcissistic graspingness, rampant Jeffersonian or Tea Party or Ayn Rand nullification. It’s a protest of mystic, epic proportions. Ask Jackie Robinson—Brooklyn second baseman, Branch Rickey- and self- nominated avatar of race equality, dutifully read about by every single schoolkid in the country, stealing home in game one of the 55 World Series—who, in his biography claimed the right and rite of dissent: “As I write this 20 years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem,” he said. “I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.” It’s a paradox at the center of everyday American life, the hue and cry of the Concord transcendentalists and liberal Constitutionalists, John Brown, Colin Kaepernick, the tricorn-hatted yeoman and doughboys charging through Belleau Wood, Jackie Robinson, rising from patriot graves, rumbling beneath the grandstand sincerity of the Anthem singers.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

The Klan in my backyard.

Reconsidering the supreme stylist's status in the canon.

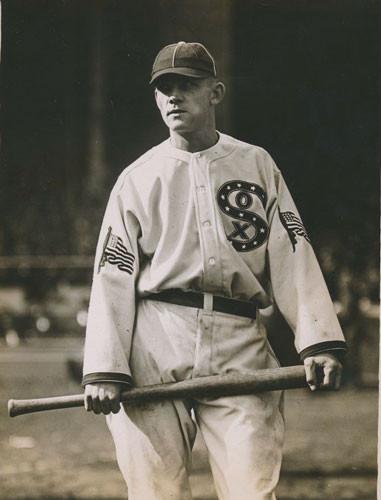

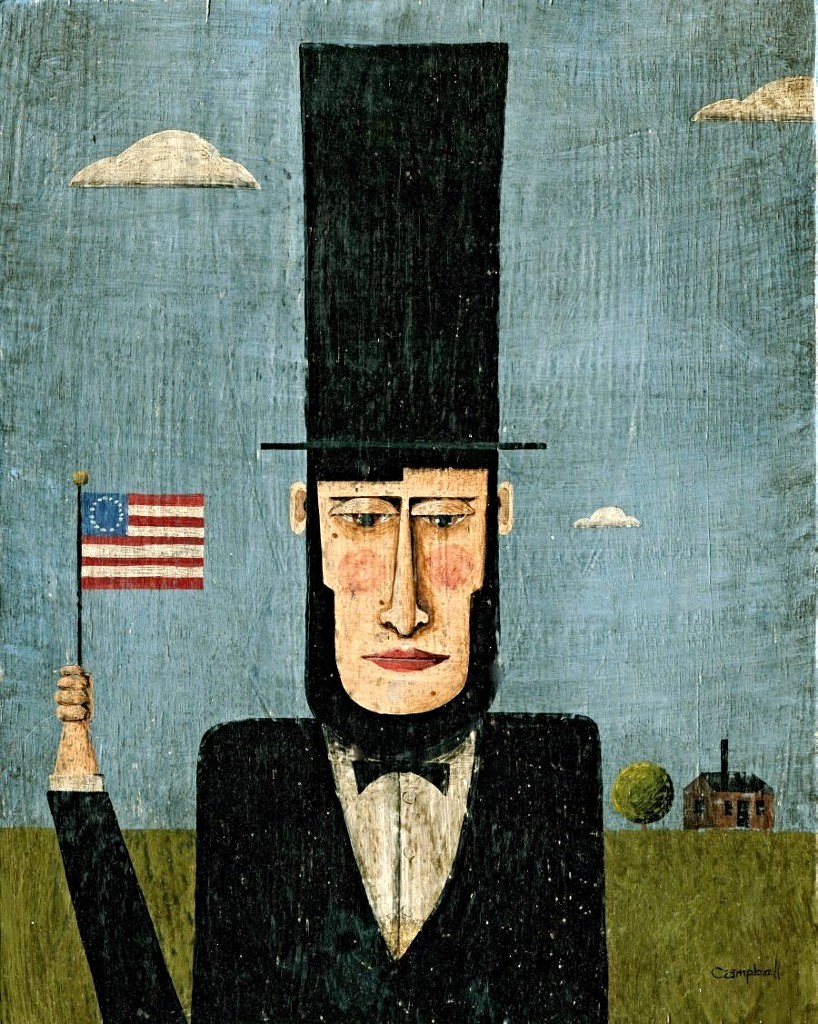

Annals of weird old America: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln & its strange aftermath.

On a cool April evening, after a dinner of cornpone and chicken fricassee, a small group—two couples, a generation apart—set out for the theater in a lacquered two-horse carriage. The women swapped little stories, fluid and familiar, while the men talked of peacetime things, farming, trains and such. The mood was just short of jovial, a neighborly parry of frontier talking, quick jabs of consonants, vowels wind-blown. The group included Clara Harris, glam socialite daughter of a New York Senator, her fiancé Major Henry Rathbone, and Mary Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln. In the carriage, rubbing the night’s slick mist from his face, the president tried out a couple new jokes. You could hear a creak when he stretched his legs. Long bones growing wintery. Henry Rathbone laughed extra hard at something Mary said. Really—the way Clara held Henry’s hand— It was Good Friday. Portents had given Abraham Lincoln grief in the past, Shakespearian, Talmudic caliber visitations of sailing at great speed—wine-black waves—but tonight he was having none of it. Not even a week had passed since Grant and Lee’s war had sputtered to an end at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, some hundred and sixty miles to the south. In the District, bells had tolled for the victory. Shattered men crutched along E Street. Mothers, widows in their weeds, made their way down Massachusetts Avenue. Tonight was for respite.

The experience of a single death unanticipated by old age, cancer, a faltering heart, has to be pretty close to universal. The soul-deep stabbing of grief, the inconsolable reflex of denial, the body’s physical revulsion, a realization of life’s chilly caprice…. In this regard was Lincoln’s death on this April night at Ford’s Theater so different from any other unexpected death? The facts of the night are part of national collective memory. We need hardly review them: the’s assigned guard goes out to a bar. The famous actor, J Wilkes Booth, familiar to the theater, presents his card to an usher— He climbs the stairs to the presidential box, and enters— Barricading the door—Drawing the derringer. The shot. Mary Lincoln screams. Blood on pretty going-out dresses. Booth slashes a dagger to fend off Major Rathbone, severing the major’s artery, then bounds off the presidential box onto the stage, breaking his leg. A born overactor. He wields the dagger like Macbeth contemplating its existence, and declares, as far as we know, Sic semper tyrannis, or some similar phrase you imagine him rehearsing in his head over and over. With a fractured fibula (conjecture as well, your honor—), Booth eludes about a dozen men trying to stop him, he seeks open ground like a fullback, mounting his waiting horse, and riding off in the gray drizzle, a blurred horseman. Actress Laura Keene makes her way into the box, cradling the president’s head in her lap while doctors, actors, stage managers, detectives swarm the place. It’s been thirty seconds, a minute, since the actor put the derringer to the back of the president’s head. Playgoers stream into the street. Lincoln’s carried to a border’s bed in a nearby house, diagonally situated because of his height, and in the ensuing hours is attended to by caretakers helpless to do more than watch, mutter in and out the door, swallowing grief.

April 15

It’s over. 7:22 this morning. You’d think with four years of unremitting killing there’d be no headroom for lamentations, but the president’s death, announced in every daily throughout the Union, signaled a new kind of mortifying clarity. Appomattox had been a false ending—

In the days after the assassination, the Confederacy still existed in theory, but was in shambles. In North Carolina, soldiers were deserting the Army of Tennessee by the thousands, the remnant simultaneously fending off Tecumseh Sherman’s forces and negotiating terms of surrender. On the run, Confederate president Jefferson Davis operated a shadow government out of a box car, lugging the treasury’s gold in wooden crates over half of Georgia and the Carolinas. Meanwhile on the night of April 23, Booth rowed across the Potomac into Virginia, nursing an increasingly painful leg. In this area, he was a known quantity, a celebrity. Swaggeringly handsome, a relatable, contemporary type, with a volatile heightened profile—Johnny Depp, Hugh Jackman. Relying on an old Confederate secret mail route, he and accomplice David Herold, a pharmacy clerk, disguised as best they could as Confederate veterans, tried to make their way deeper South.

April 21

“Carrying a corpse to where it shall rest in the grave, Night and day journeys a coffin,” wrote Whitman. Lincoln’s funeral train wended along 1700 miles of track toward Springfield, stopping along the way: Harrisburg, Herkimer, Buffalo, Erie, Indianapolis, Joliet— Such conspicuously American sounding place-names! Black crepe had replaced the patriotic bunting of the previous week, hanging from every storefront and counting house. Rocking through the night, the train came upon bonfires, torchlights— otherworldly stabs of light in otherwise prairie darkness. Massed voices singing, “Farewell Father, Friend and Guardian.”

Not only had he presided over the Civil War, but Lincoln had given its military exigencies a political, rhetorical, moral shape, transforming tableaus of summer marches, the smashed, eviscerated bodies in mass graves, into something resembling a classical tragedy. The Second Inaugural address, a valedictory delivered on a frigid March afternoon a little more than a month before the assassination, set him and his political agenda up for national transcendence. “With malice toward none, with charity for all….” Whitman too picked up on the benevolent mood, casting the “varied and ample land, the South and the North in the light, Ohio’s shores and flashing Missouri” in poeticized unity.

It’s impossible to know the extent to which malice toward none would have functioned as actual policy—it’s a tough sell in light of the national calamity of Reconstruction—but Lincoln possessed a probing adaptability to shifting meanings, subtle and not-so-subtle (a gradual emancipationist, he’d taken nominal Union victory at Antietam Creek in September of 62 to articulate the war’s ultimate meaning, and compelled emancipation to the foreground of the war’s aims). In photographs of him delivering the Second Inaugural on the steps of the just finished Capitol, with Booth in attendance, we see him bent forward, intent on the page in his hand. It’s the bearded, haunted, disembodied, visage of our dreamlike imagining of him: the one of the common penny, Rushmore, the fiver. He might already be dead.

But yet— Yet— In 64 Lincoln barely mustered enough votes to win a second term. The victory came mostly thanks to the states’ introduction of absentee voting, besides the votes of furloughed soldiers, and news of Tecumseh Sherman wrecking his way through the Carolinas. In his first term he’d been ridiculed in the press as bungling—a laughingstock to doyens like Henry Adams, who saw in his “plain, ploughed face; a mind, absent in part… above all a lack of apparent force.” But even Wilkes Booth lived long enough to confront the folly of this underestimation. Instead of being hailed as a Confederate Cassius, as he’d expected, Booth had been chased to the end of his line, and instead of triumph, found only condemnation. Lincoln’s death was, “the heaviest blow which has fallen on the people of the south,” wrote an editor on the Richmond Whig. “And why?” Booth scribbled in his pocket diary as Federal troops sought to flush him out of his hiding spot. “For doing what Brutus was honored for.… And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

April 26

Shortly after midnight, acting on tips from locals, twenty-some members of the 16th New York Cavalry canter up to the Garrett farm, outside Port Royal, Virginia, and set up a cordon around Booth’s hide-out. There’s no textbook for taking prisoner a presidential assassin who’s hiding out in a locked tobacco barn with a cache of weapons, any more than there’s a textbook for the assassin who’s hobbling about the barn with one good leg, calculating chances of a Wild West escape. But when the troops surround the barn, and demand Booth and Herold’s surrender, Booth offers the soldiers a deal—a duel at fifty paces—a last-ditch stage show for posterity, the only plausible result being that he’ll be gunned down in his own play, a showy martyr to the cause (the “Cause” had yet to be lost, Lost Cause yet to be articulated as Southern raison d’être) living on in posterity. The detachment’s commander demurs and orders the barn set on fire. Herold emerges, hands up. Booth, carbine rifle against his hip, tauntingly remains. A sergeant with the notably extravagant name of Boston Corbett had earlier volunteered to go in and fight it out with Booth in the barn, mano-a-mano, but now Sergeant Corbett takes aim at the flickering figure behind the barn slats, and squeezes the trigger, felling Booth. Heat presses the men’s brows and beards, they go in and drag the fugitive to the Garretts’ porch, a specimen pinned to a board, the matinee idol mustache wet with snot. Sunlight’s coming up, laundering the night air. The barn’s reduced to persistent embers and a tangle of burnt machinery. By now neighbors, curiosity seekers, tramp up through the morning light to join the vigil, hanging around in hopes of witnessing close up something that will get remembered, people will talk about and say they were there when of course they weren’t. It’s an hour, two, before the man stops asking for water, his breathing going shallow, then, finally, his eyes like dried river stones staring into the new day.

Booth’s desire to slay a tyrant and possibly become himself a Confederate martyr was inverted in apposite cruelty. In killing Lincoln, he’d achieved a measure of eternal notoriety that his acting, however popular in its time, had zero chance of bringing him, leastwise eternally. But in his last minutes he must have come to understand the irony that he was forever subordinate. His name would never be mentioned again without reference to Lincoln. Thousands of schoolchildren every year visit Ford’s Theater. The Garrett house collapsed into rubble decades ago, there’s a scant sign on the median between the northbound and southbound lanes of US 301.

Postscripts:

Four days later Lincoln’s funeral train reached Springfield. The bodies of the president and his son Willie, who’d died of typhoid three years earlier, were interred in a hastily constructed vault in the Oak Ridge Cemetery on the outskirts of town. Five days after the burial, Jefferson Davis and his reduced entourage, running out of places to run, cross the Ocmulgee, near Irwinville, Georgia. They stake up their tents by a little creek, gypsies, wayfarers, disguised exiles. The Federal authorities, in the form of the 4th Michigan, 1st Wisconsin, are a few miles behind. Cavalry. Wild azaleas, buttercups, foamflower, are in bloom. Night calms the buzzing of the honeybees. Before dawn a smatter of rifle fire comes cracking along the creek, and Davis, bone tired of running you’d guess, unbends out of his field tent. Stooped. Maybe a little nearsighted, trying to find spectacles. His face gone whiskery. Taste of recent tobacco in his teeth. He runs—a few yards toward the creek. And realizes—

For the next two years he lives like others—biscuits, water, pacing the parapets of Fort Monroe. Indicted for treason for which he’ll never stand trial. He’d been at this fort before, as Secretary of State, President of the Confederacy, an understated leader of men, his name blooming in fireworks in the night sky.

It’s July now. July in the District, in the courtyard of a prison. Miasma blankets the Capital’s marshes and lowlands. Heat settling in for the duration. You could get tickets for the hanging if you were lucky. Best if you remembered a parasol though. Booth’s associates—the conspirators—struggle up the scaffold stairs in the courtyard, helped to their seats by a courteous hand. Their feet and hands are bound. David Herold, Lewis Payne, Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt. These things happen with a speed that feels unjust. The order for their execution is read, and the heads duck forward to receive the hoods, they are led two steps forward to the trap doors, a scent of new lumber coming through the hoods. A pair of hands claps, the doors swing down, the bodies jolt, swing, settle. But the living men and woman twitch, some in the crowd turning away, some starting to register. There’s been a miscalculation. It takes minutes for the ropes to press the air out of them. In his vaulted cell less than two hundred miles away, Jefferson Davis wonders about his own fate. “President Johnson,” he says, “is very quick on the trigger.”

Postscripts. Postscripts. In America, postscripts have this antic quality of the high grotesque, don’t they? Pathos mixed with a hoot. Meaning drifting into the weirdest corners. One Boston Corbett, high on mercury nitrate, mad as a hatter, drifts in and out of the nineteenth century’s chugging milieu, a quasi-mystic who’d come after you with his fists, pistols, for saying hell, resolutely parted hair and a madman’s eyes. Approached by prostitutes, so as not to be led unto temptation he cut off his testicles with scissors, a eunuch preaching on a soapbox. For a while he toured churches, little theaters, with lantern shows of the scene at Garrett’s barn. He mimed his aim. It didn’t have to be Boston Corbett who shot Booth, it could have been Private Smith, Corporal Jenkins, but it’s Corbett the zealot who signifies the ambient madness of the times.

More postscripts. Colonel Henry Rathbone survived Booth’s dagger to marry Miss Clara Harris, his ringletted step-sister (you heard that right— step-sister). Seventeen years after the assassination, president Chester Arthur appointed him Consul to the Province of Hanover, Germany. Then one morning, increasingly prone to delusion (it had been a problem for a while—), Consul Rathbone drew a pistol on Clara, who’d been in bed, killed her, and in should-be-but-isn’t droll replication of events at Fords Theater, stabbed himself over and over. Committed to an asylum outside Hildesheim, the Consul lived out his days, another madman pacing the asylum.

One last. Too good to pass up. In 1903 a theatrically inclined housepainter, David E George, claiming to be John Wilkes Booth, borrowing the actor’s infamy, ended it all in a locked hotel room, with a dose of arsenic. For a few years the housepainter’s embalmed body sat in the window of a mortuary and furniture store in Enid, Oklahoma, nattily attired, reading the day’s newspaper, advertising the establishment. This is true. Look it up. Eventually an enterprising carnival impresario who’d known George purchased the mummified body, taking it on the road alongside bearded ladies, three-legged men, propping it up as the man who killed Abraham Lincoln. There’s a resemblance. The mustache. The chin. And you can imagine George’s posthumous satisfaction at being represented as Booth. For more than five decades the mummy was packed in and out of steamer trunks; then by all reports it vanished sometime in the 1970s. Mummified assassins, real or otherwise, probably held little cultural currency in a tv-saturated landscape. But how it was that David E George and John Wilkes Booth might have been one in the same hints at something more than a bunch of willing dupes plunking down their nickels to get a gander. The story had it that Andrew Johnson had orchestrated Lincoln’s assassination. It wasn’t Booth killed in Garrett’s barn back in 1865 but someone else. A patsy maybe. While Booth, of course, lived on as David E George, painting houses, doing bits of Lear and MacBeth for the locals, until making a comeback as a sideshow oddity. The story hints at shady propositions so unlikely there’s no question about their authenticity. Sergeant Corbett was in on it too.

Democracy tells us, not-so subliminally, to pursue our own mystic dreams. Since, say, the Salem trials Americans have been fantasizing about dark forces, secret cabals, information passed in alleyways. The deep state. Some broodingly underground, unhinged version of American life. Sometimes it’s a wonder that the nearly unelectable Lincoln of 64, stumbling and inconsistent, losing a misbegotten war, ever got any credit at all. His earnestness was the most foolhardy posture in history. Then Booth’s .44 caliber bullet started in motion the sanctification of the man he hoped to obliterate.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

The Klan in my backyard.