A brief history of being young & adrift in 80s New York.

More

Annals of weird old America: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln & its strange aftermath.

On a cool April evening, after a dinner of cornpone and chicken fricassee, a small group—two couples, a generation apart—set out for the theater in a lacquered two-horse carriage. The women swapped little stories, fluid and familiar, while the men talked of peacetime things, farming, trains and such. The mood was just short of jovial, a neighborly parry of frontier talking, quick jabs of consonants, vowels wind-blown. The group included Clara Harris, glam socialite daughter of a New York Senator, her fiancé Major Henry Rathbone, and Mary Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln. In the carriage, rubbing the night’s slick mist from his face, the president tried out a couple new jokes. You could hear a creak when he stretched his legs. Long bones growing wintery. Henry Rathbone laughed extra hard at something Mary said. Really—the way Clara held Henry’s hand— It was Good Friday. Portents had given Abraham Lincoln grief in the past, Shakespearian, Talmudic caliber visitations of sailing at great speed—wine-black waves—but tonight he was having none of it. Not even a week had passed since Grant and Lee’s war had sputtered to an end at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, some hundred and sixty miles to the south. In the District, bells had tolled for the victory. Shattered men crutched along E Street. Mothers, widows in their weeds, made their way down Massachusetts Avenue. Tonight was for respite.

The experience of a single death unanticipated by old age, cancer, a faltering heart, has to be pretty close to universal. The soul-deep stabbing of grief, the inconsolable reflex of denial, the body’s physical revulsion, a realization of life’s chilly caprice…. In this regard was Lincoln’s death on this April night at Ford’s Theater so different from any other unexpected death? The facts of the night are part of national collective memory. We need hardly review them: the’s assigned guard goes out to a bar. The famous actor, J Wilkes Booth, familiar to the theater, presents his card to an usher— He climbs the stairs to the presidential box, and enters— Barricading the door—Drawing the derringer. The shot. Mary Lincoln screams. Blood on pretty going-out dresses. Booth slashes a dagger to fend off Major Rathbone, severing the major’s artery, then bounds off the presidential box onto the stage, breaking his leg. A born overactor. He wields the dagger like Macbeth contemplating its existence, and declares, as far as we know, Sic semper tyrannis, or some similar phrase you imagine him rehearsing in his head over and over. With a fractured fibula (conjecture as well, your honor—), Booth eludes about a dozen men trying to stop him, he seeks open ground like a fullback, mounting his waiting horse, and riding off in the gray drizzle, a blurred horseman. Actress Laura Keene makes her way into the box, cradling the president’s head in her lap while doctors, actors, stage managers, detectives swarm the place. It’s been thirty seconds, a minute, since the actor put the derringer to the back of the president’s head. Playgoers stream into the street. Lincoln’s carried to a border’s bed in a nearby house, diagonally situated because of his height, and in the ensuing hours is attended to by caretakers helpless to do more than watch, mutter in and out the door, swallowing grief.

April 15

It’s over. 7:22 this morning. You’d think with four years of unremitting killing there’d be no headroom for lamentations, but the president’s death, announced in every daily throughout the Union, signaled a new kind of mortifying clarity. Appomattox had been a false ending—

In the days after the assassination, the Confederacy still existed in theory, but was in shambles. In North Carolina, soldiers were deserting the Army of Tennessee by the thousands, the remnant simultaneously fending off Tecumseh Sherman’s forces and negotiating terms of surrender. On the run, Confederate president Jefferson Davis operated a shadow government out of a box car, lugging the treasury’s gold in wooden crates over half of Georgia and the Carolinas. Meanwhile on the night of April 23, Booth rowed across the Potomac into Virginia, nursing an increasingly painful leg. In this area, he was a known quantity, a celebrity. Swaggeringly handsome, a relatable, contemporary type, with a volatile heightened profile—Johnny Depp, Hugh Jackman. Relying on an old Confederate secret mail route, he and accomplice David Herold, a pharmacy clerk, disguised as best they could as Confederate veterans, tried to make their way deeper South.

April 21

“Carrying a corpse to where it shall rest in the grave, Night and day journeys a coffin,” wrote Whitman. Lincoln’s funeral train wended along 1700 miles of track toward Springfield, stopping along the way: Harrisburg, Herkimer, Buffalo, Erie, Indianapolis, Joliet— Such conspicuously American sounding place-names! Black crepe had replaced the patriotic bunting of the previous week, hanging from every storefront and counting house. Rocking through the night, the train came upon bonfires, torchlights— otherworldly stabs of light in otherwise prairie darkness. Massed voices singing, “Farewell Father, Friend and Guardian.”

Not only had he presided over the Civil War, but Lincoln had given its military exigencies a political, rhetorical, moral shape, transforming tableaus of summer marches, the smashed, eviscerated bodies in mass graves, into something resembling a classical tragedy. The Second Inaugural address, a valedictory delivered on a frigid March afternoon a little more than a month before the assassination, set him and his political agenda up for national transcendence. “With malice toward none, with charity for all….” Whitman too picked up on the benevolent mood, casting the “varied and ample land, the South and the North in the light, Ohio’s shores and flashing Missouri” in poeticized unity.

It’s impossible to know the extent to which malice toward none would have functioned as actual policy—it’s a tough sell in light of the national calamity of Reconstruction—but Lincoln possessed a probing adaptability to shifting meanings, subtle and not-so-subtle (a gradual emancipationist, he’d taken nominal Union victory at Antietam Creek in September of 62 to articulate the war’s ultimate meaning, and compelled emancipation to the foreground of the war’s aims). In photographs of him delivering the Second Inaugural on the steps of the just finished Capitol, with Booth in attendance, we see him bent forward, intent on the page in his hand. It’s the bearded, haunted, disembodied, visage of our dreamlike imagining of him: the one of the common penny, Rushmore, the fiver. He might already be dead.

But yet— Yet— In 64 Lincoln barely mustered enough votes to win a second term. The victory came mostly thanks to the states’ introduction of absentee voting, besides the votes of furloughed soldiers, and news of Tecumseh Sherman wrecking his way through the Carolinas. In his first term he’d been ridiculed in the press as bungling—a laughingstock to doyens like Henry Adams, who saw in his “plain, ploughed face; a mind, absent in part… above all a lack of apparent force.” But even Wilkes Booth lived long enough to confront the folly of this underestimation. Instead of being hailed as a Confederate Cassius, as he’d expected, Booth had been chased to the end of his line, and instead of triumph, found only condemnation. Lincoln’s death was, “the heaviest blow which has fallen on the people of the south,” wrote an editor on the Richmond Whig. “And why?” Booth scribbled in his pocket diary as Federal troops sought to flush him out of his hiding spot. “For doing what Brutus was honored for.… And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

April 26

Shortly after midnight, acting on tips from locals, twenty-some members of the 16th New York Cavalry canter up to the Garrett farm, outside Port Royal, Virginia, and set up a cordon around Booth’s hide-out. There’s no textbook for taking prisoner a presidential assassin who’s hiding out in a locked tobacco barn with a cache of weapons, any more than there’s a textbook for the assassin who’s hobbling about the barn with one good leg, calculating chances of a Wild West escape. But when the troops surround the barn, and demand Booth and Herold’s surrender, Booth offers the soldiers a deal—a duel at fifty paces—a last-ditch stage show for posterity, the only plausible result being that he’ll be gunned down in his own play, a showy martyr to the cause (the “Cause” had yet to be lost, Lost Cause yet to be articulated as Southern raison d’être) living on in posterity. The detachment’s commander demurs and orders the barn set on fire. Herold emerges, hands up. Booth, carbine rifle against his hip, tauntingly remains. A sergeant with the notably extravagant name of Boston Corbett had earlier volunteered to go in and fight it out with Booth in the barn, mano-a-mano, but now Sergeant Corbett takes aim at the flickering figure behind the barn slats, and squeezes the trigger, felling Booth. Heat presses the men’s brows and beards, they go in and drag the fugitive to the Garretts’ porch, a specimen pinned to a board, the matinee idol mustache wet with snot. Sunlight’s coming up, laundering the night air. The barn’s reduced to persistent embers and a tangle of burnt machinery. By now neighbors, curiosity seekers, tramp up through the morning light to join the vigil, hanging around in hopes of witnessing close up something that will get remembered, people will talk about and say they were there when of course they weren’t. It’s an hour, two, before the man stops asking for water, his breathing going shallow, then, finally, his eyes like dried river stones staring into the new day.

Booth’s desire to slay a tyrant and possibly become himself a Confederate martyr was inverted in apposite cruelty. In killing Lincoln, he’d achieved a measure of eternal notoriety that his acting, however popular in its time, had zero chance of bringing him, leastwise eternally. But in his last minutes he must have come to understand the irony that he was forever subordinate. His name would never be mentioned again without reference to Lincoln. Thousands of schoolchildren every year visit Ford’s Theater. The Garrett house collapsed into rubble decades ago, there’s a scant sign on the median between the northbound and southbound lanes of US 301.

Postscripts:

Four days later Lincoln’s funeral train reached Springfield. The bodies of the president and his son Willie, who’d died of typhoid three years earlier, were interred in a hastily constructed vault in the Oak Ridge Cemetery on the outskirts of town. Five days after the burial, Jefferson Davis and his reduced entourage, running out of places to run, cross the Ocmulgee, near Irwinville, Georgia. They stake up their tents by a little creek, gypsies, wayfarers, disguised exiles. The Federal authorities, in the form of the 4th Michigan, 1st Wisconsin, are a few miles behind. Cavalry. Wild azaleas, buttercups, foamflower, are in bloom. Night calms the buzzing of the honeybees. Before dawn a smatter of rifle fire comes cracking along the creek, and Davis, bone tired of running you’d guess, unbends out of his field tent. Stooped. Maybe a little nearsighted, trying to find spectacles. His face gone whiskery. Taste of recent tobacco in his teeth. He runs—a few yards toward the creek. And realizes—

For the next two years he lives like others—biscuits, water, pacing the parapets of Fort Monroe. Indicted for treason for which he’ll never stand trial. He’d been at this fort before, as Secretary of State, President of the Confederacy, an understated leader of men, his name blooming in fireworks in the night sky.

It’s July now. July in the District, in the courtyard of a prison. Miasma blankets the Capital’s marshes and lowlands. Heat settling in for the duration. You could get tickets for the hanging if you were lucky. Best if you remembered a parasol though. Booth’s associates—the conspirators—struggle up the scaffold stairs in the courtyard, helped to their seats by a courteous hand. Their feet and hands are bound. David Herold, Lewis Payne, Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt. These things happen with a speed that feels unjust. The order for their execution is read, and the heads duck forward to receive the hoods, they are led two steps forward to the trap doors, a scent of new lumber coming through the hoods. A pair of hands claps, the doors swing down, the bodies jolt, swing, settle. But the living men and woman twitch, some in the crowd turning away, some starting to register. There’s been a miscalculation. It takes minutes for the ropes to press the air out of them. In his vaulted cell less than two hundred miles away, Jefferson Davis wonders about his own fate. “President Johnson,” he says, “is very quick on the trigger.”

Postscripts. Postscripts. In America, postscripts have this antic quality of the high grotesque, don’t they? Pathos mixed with a hoot. Meaning drifting into the weirdest corners. One Boston Corbett, high on mercury nitrate, mad as a hatter, drifts in and out of the nineteenth century’s chugging milieu, a quasi-mystic who’d come after you with his fists, pistols, for saying hell, resolutely parted hair and a madman’s eyes. Approached by prostitutes, so as not to be led unto temptation he cut off his testicles with scissors, a eunuch preaching on a soapbox. For a while he toured churches, little theaters, with lantern shows of the scene at Garrett’s barn. He mimed his aim. It didn’t have to be Boston Corbett who shot Booth, it could have been Private Smith, Corporal Jenkins, but it’s Corbett the zealot who signifies the ambient madness of the times.

More postscripts. Colonel Henry Rathbone survived Booth’s dagger to marry Miss Clara Harris, his ringletted step-sister (you heard that right— step-sister). Seventeen years after the assassination, president Chester Arthur appointed him Consul to the Province of Hanover, Germany. Then one morning, increasingly prone to delusion (it had been a problem for a while—), Consul Rathbone drew a pistol on Clara, who’d been in bed, killed her, and in should-be-but-isn’t droll replication of events at Fords Theater, stabbed himself over and over. Committed to an asylum outside Hildesheim, the Consul lived out his days, another madman pacing the asylum.

One last. Too good to pass up. In 1903 a theatrically inclined housepainter, David E George, claiming to be John Wilkes Booth, borrowing the actor’s infamy, ended it all in a locked hotel room, with a dose of arsenic. For a few years the housepainter’s embalmed body sat in the window of a mortuary and furniture store in Enid, Oklahoma, nattily attired, reading the day’s newspaper, advertising the establishment. This is true. Look it up. Eventually an enterprising carnival impresario who’d known George purchased the mummified body, taking it on the road alongside bearded ladies, three-legged men, propping it up as the man who killed Abraham Lincoln. There’s a resemblance. The mustache. The chin. And you can imagine George’s posthumous satisfaction at being represented as Booth. For more than five decades the mummy was packed in and out of steamer trunks; then by all reports it vanished sometime in the 1970s. Mummified assassins, real or otherwise, probably held little cultural currency in a tv-saturated landscape. But how it was that David E George and John Wilkes Booth might have been one in the same hints at something more than a bunch of willing dupes plunking down their nickels to get a gander. The story had it that Andrew Johnson had orchestrated Lincoln’s assassination. It wasn’t Booth killed in Garrett’s barn back in 1865 but someone else. A patsy maybe. While Booth, of course, lived on as David E George, painting houses, doing bits of Lear and MacBeth for the locals, until making a comeback as a sideshow oddity. The story hints at shady propositions so unlikely there’s no question about their authenticity. Sergeant Corbett was in on it too.

Democracy tells us, not-so subliminally, to pursue our own mystic dreams. Since, say, the Salem trials Americans have been fantasizing about dark forces, secret cabals, information passed in alleyways. The deep state. Some broodingly underground, unhinged version of American life. Sometimes it’s a wonder that the nearly unelectable Lincoln of 64, stumbling and inconsistent, losing a misbegotten war, ever got any credit at all. His earnestness was the most foolhardy posture in history. Then Booth’s .44 caliber bullet started in motion the sanctification of the man he hoped to obliterate.

You might be interested in

The End through the ages. How we see everything we don't know.

In 1859 John Brown attempted to incite a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The events of those days became

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

The Klan in my backyard.

A brief history of being young & adrift in 80s New York.

In my young twenties I moved to Brooklyn. At the time moving to Brooklyn was a ritual experience for many young people, like moving to Paris between the world wars must have been, I suppose, or Los Angeles would be for certain cultural adventurers in the 2010s. It was the 80s, before New York became a fairytale mecca, and along with discovering yourself you could also discover multi-chambered LIRR stations with long- shuttered coffee and flower shops, shoe-shine stations, or you could take the train into Times Square and experience the smug seediness of the genuine article, and claim to be living an outré, bohemian life. You could, in other words, still live in relative comfort for not too much money, provided your requirements for comfort entailed no more than an occasional slice of pizza or a few beers on the weekend.

My roommate and I lived quite shabbily in a one-bedroom off DeKalb with a backyard garden we neglected, and a heater that inexplicably turned off on weekends, as if anticipating that we were going to be away in Vermont or the Hamptons, which of course we never were. On all sides, our neighborhood was hemmed in by other neighborhoods where drug deals went down and people were occasionally murdered in rank, dispirited walk-ups. But our street and two or three that ran parallel to ours were shaded with ancient oaks and London Plain trees, there was a park nearby where we would play tennis, and I would run, doing endless loops on a hard-packed path. It had once been solidly middle class but was between prosperous periods now.

Next to our apartment building was a grand abandoned hotel with a marble staircase more or less intact. Sometimes my roommate and I scaled the rusted-out fire escape between the buildings to the fourth story to get inside. You had to stretch your body its full extent and jerk through an open window, a foolhardy move that could have resulted in catastrophe. But once in, you had free rein. Everywhere was debris, horsehair plaster, broken glass, wet slabs of cardboard, wreckage we pawed through in search of some kind of glittering souvenirs. I don’t recall ever discovering anything of value or interest but it was just as well; material evidence of our adventures was superfluous. Phantoms always exerted the most powerful psychic force on me. I’d come to Brooklyn to commune with the likes of Hart Crane and Walt Whitman, who I imagined hovering among the wharfs and printing rooms and ale houses. I wanted to merge with intangible presences, impressing centuries’ of layered ghosts into the crannies of the novel I was writing.

To make ends meet, my roommate got a job with a company that collated dossiers on big businesses. Pretty soon he was making a halfway decent salary. For my part, I was barely keeping alive, financially speaking. I had a couple jobs, one teaching English part-time at a yeshiva, another as a ticket taker at a Manhattan cinema that no longer exists. I often borrowed money from him to cover the rent, and paid him back a few weeks later. A cycle as futile as it was routine. I was forever in small debt to him; and he was forever being outwardly tolerant of the situation. His bed was in the apartment’s only bedroom, mine was in the living room, an arrangement that didn’t seem to cause as much debate or grief as one had a right to expect. We’d been friends in college, and were used to each other, no doubt, and instinctively knew to defer to each other’s claim to the kitchen or the demoralized blue couch he’d brought to the apartment—a luxury, if you could call it that, that made me feel so grown up. Until that time, I hadn’t been acquainted with anyone my age who owned living room furniture.

My roommate was an actor, often away on auditions or seeing plays. Most every free minute I wrote. My novel, about a Confederate soldier, Thomas Leroix, who’d ended up in Kansas after the war, trying to make peace with his memories, was progressing at a steady pace. I’d traveled a fair bit in the South, enough, so I assumed, to unflinchingly assimilate the magnolia-scented horrors of its past into the pages of the book.

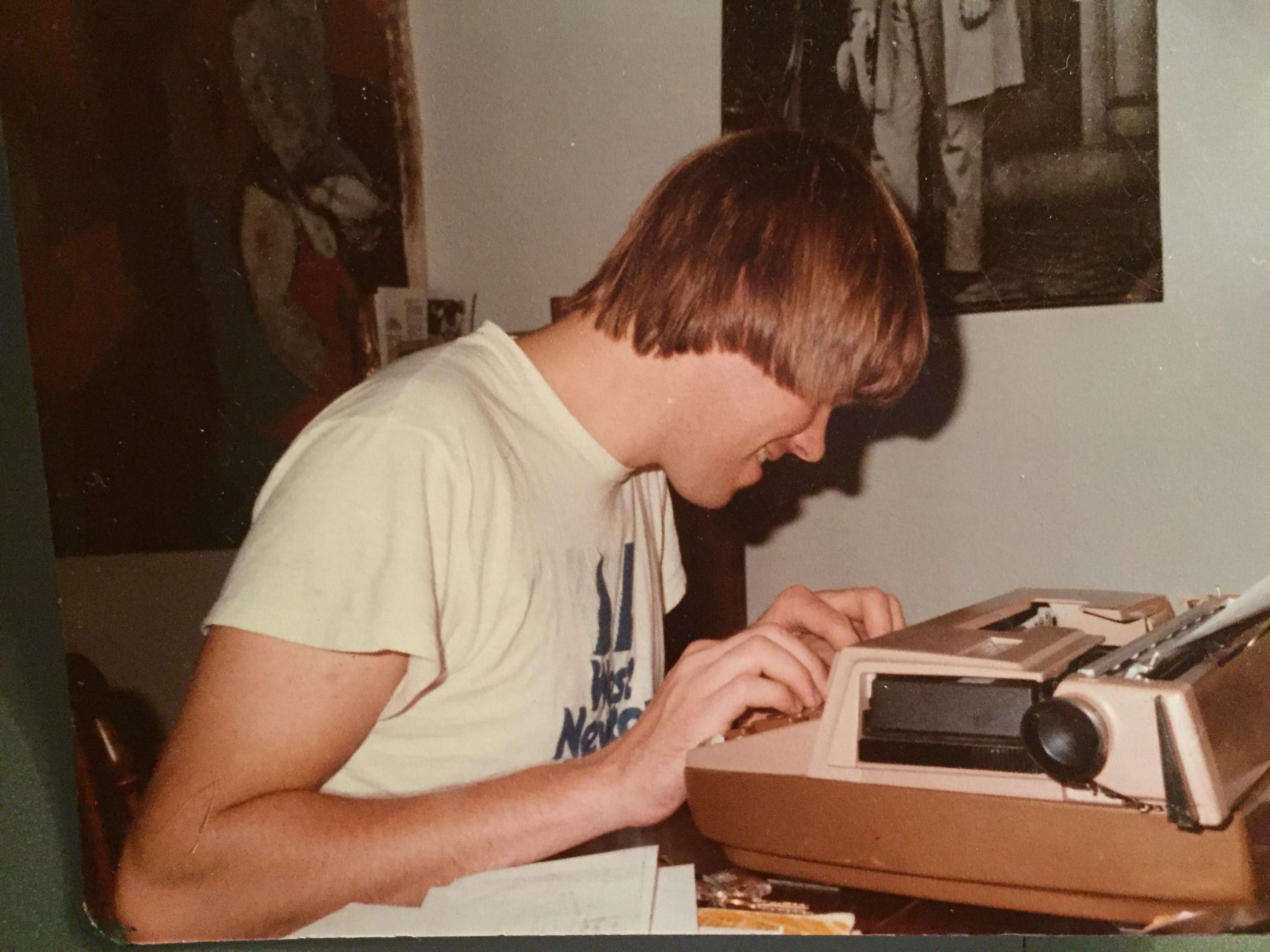

Nowadays manuscripts, I assume, are released into existence as if summoned from a hushed electronic ether (in fact I’m writing this on a laptop), no more tactile than a passing thought, but then I typed on an electric typewriter. And the once-ubiquitous sound of typewriters—the commiserative hum of electric motors, the stored words tumbling forward in a clacking barrage—elicits in me now a keening nostalgia for sitting at what passed as our dining room table, as Brooklyn nights gathered outside. Doubtless typing wasn’t so romantic to my roommate when he was home watching Barney Miller behind the closed bedroom door, smoking the sample cigarettes they gave out in the street then to keep you hooked or get you started. Sometimes it woke him up in the middle of the night, and I’d whisper apologies through his door. I spent hardly any time on the lesson plans, trying to squeeze in as much time writing as possible. But thus did the strange novel grow, astonishingly, page upon page compounding upon our dining table.

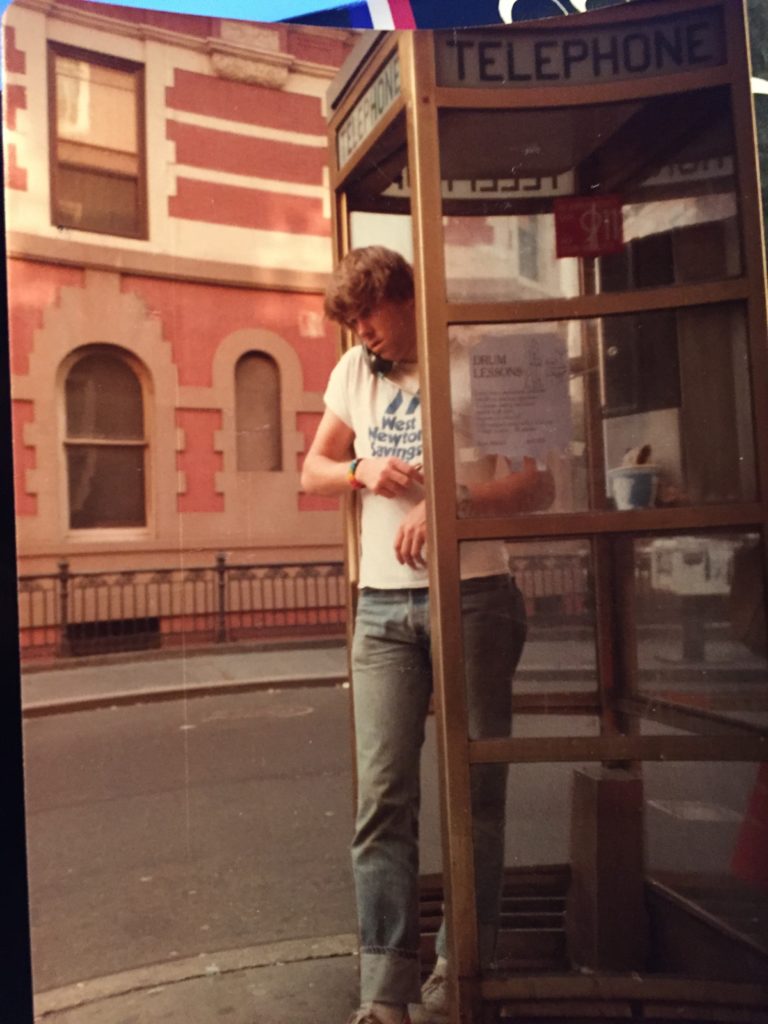

I was, of course, eager to get out of the apartment too. I’d take the subway—and, appeasing ever-shifting exigencies of time and money, seldom paid the fare. I’ll admit to feeling some niggling shame, but a subway token (emblem of an evergreen, irretrievable New York: brass-colored with a silver bullseye center) cost, if I recall, a dollar, not nothing for someone in my position. So I became adept at hopping turnstiles, perfecting a means of slipping through the gates undetected by the station attendants, who presided in their bulletproof glass booths like abbots in their personal refectories. It was thrilling to be able to get around the city for free, riding to the far-flung polarities of Rockaway, Sheepshead Bay, Pelham Bay Park, as if under new-found power. Unbound from my desk, I’d explore regions of the city so far-flung it was quite possible that denizens of one section had no more idea of the existence of the other than South Seas islanders had of emirs of the Ottoman Empire. In warmer weather, I’d bicycle through Prospect Park, sucking in exhaust fumes. Nights speeding down Flatbush, Bedford Avenue, where Ebbetts Field used to stand, past check cashing and pizza joints, Dirty Bud’s Recovery Room, the original Juniors, which staked out the corner of Dekalb and Flatbush like an extravagant, generous-hearted hooker—a thrilling manumission, an avowal of the untempered joy that seized my body, as when I learned to ride on the tar-and-gravel streets of the Boston suburbs of my boyhood. Sometimes I’d run along the pedestrian walk on the Brooklyn Bridge, one of the most dazzling spectacles in the country, gazing out at the Liberty Statue, the Twin Towers, and down at the gray river coursing out to sea. In awe of such moments, one felt genuine patriotism and pride in a country in which it wasn’t always easy to lay claim to such unfashionable feelings.

To be poor in New York is to be forever looking in at a rarefied and glittering bubble, a gilded shelter; but the vantage of the poor can sometimes afford the greater prospect, I like to think: the perspective of a threadbare god. The booth of the movie theater where I worked faced 7th Avenue; from this angle a ticket seller would look out at the steady procession of pedestrians strolling by, some of whom would stop and talk to us through the intercom. The wealthy, the destitute, the lost… the intercom amplified their voices over the street’s jabber and strife, as if petitioning a convenient deity. One guy, a regular, a small conspiratorial man in a suit jacket three times too big for him and his few remaining teeth situated far back in his mouth, had been, he said, a trumpeter in a famous jazz combo decades ago. Hard times had befallen him, he didn’t have to say. He’d regale us with stories of long-defunct jazz clubs, Chet Baker, Ellington. Then you’d see him around town sometimes, telling the same stories to people who could turn their backs to him.

A coworker of mine, the son of an actor you’d recognize from tv and a few movies, was always bowled over at characters like this. He’d grown up in New York, presumably, but for some reason the New York scenes and characters he must have been around since birth remained forever novel, his capacity for astonishment perennially refreshed. Look at that guy, he’d say, clamping his forehead with his hand. Can you believe it? Over and over again. Look at that guy. He was right, of course. There were characters in New York. There were always people of all kinds to look at. One night after the movie had been playing a while, Bob Dylan came in with Merry Clayton, the singer of the indelible Rape, murder… line in the Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter. Dylan must have been in a down phase, musically speaking; he looked like he was trying to keep up, fashion-wise.

Still, there are few people more universally Dylan-like than Dylan; and in the middle of the movie he wandered into the lobby, his eyes even in repose had a wary, quicksilver flash of a fox’s with a chicken in its jaws. I thought to say something to him, talk to him like I was talking through the window in the ticket booth, but didn’t see the point.

Everything you had to know about him, I figured, you already got from the songs and the cowboy boots he was wearing. Before the movie finished, he and Merry Clayton slipped out. Susan Sontag, Bill Murray, other music and literature and movie people also came in sometimes, but my life was peripheral to all that then, it was starting out on its own course, and would, I hope, find its way too.

My boss at the cinema later became a pretty well-known film critic. The two of us would go together to broken-down theaters near Times Square, the Upper West Side and the Village. They smelled in those days, universally, of dereliction and pee, and showed scratched-up prints of old John Wayne westerns, Bergman, the standard Fassbinder or Goddard or Buñuel repertory. The ticket takers, seen-it-all boys my age, or gray Beat eminences, ran fingers down their lists before admitting us. In one such palace, around 42nd Street, a glum joint that sometimes screened porn, we watched a movie that was to become a personal favorite. The Last Picture Show. If you haven’t seen it, do. The Last Picture Show (1971) yielded a thousand vicarious thrills, mostly to do with the romance of watching lives decompose in a simulacrum of real time. On the screen, the textured Texas wastelands, on the periphery of civilization, showed an America forever endangered, intended to be plowed under. It was in The Last Picture Show that I heard Hank Williams for the first time, singing “I Can’t Help It If I’m Still In Love With You” as if from a new grave. In Picture Show’s landscape, doors were always rattling on loose hinges. Tumbleweeds cartwheeled in dust-blown streets. In one scene, arguably one of the most affecting in the history of American cinema, a gym teacher’s wife (Cloris Leachman) confronts her high-school age lover (Timothy Bottoms), who scarcely knows how or where his decency got lost. His eyes hold out hope for redemption he knows can’t be given. Hers is a quintessentially and exclusively American face, like one in a Walker Evans picture, its frayed edges abounding in patriotism. Hurling a coffee pot against a wall, Cloris herself abounds in gestures of love and regret. We wait. Wracked. Rooting for her but thinking, too late, too late. Hank Williams sings. A boy is killed—a narrative jolt that feels precisely right in its recognition that life owes nothing. The lights of the theater come up. We stretch our legs and leave. Outside a glorious spring afternoon. New York suddenly seems small, provincial, its bluster something disagreeable and gratuitous.

I stayed in New York a few months after that. I took another part-time job, tutoring a student on the Upper East Side. It was almost summer, a few nights a week I hopped the Lexington line to an apartment on York and the 90s, where I tutored the girl in English and history; but after a while it became apparent that the tutoring agency that had hired me was a con, I hadn’t received a single check. I left messages that weren’t returned, and ended up in court with a bunch of other duped tutors. The defendant didn’t show, of course; we tutors, having won our case, departed the courtroom single file, having spent yet another day chasing paychecks we knew we’d never get. It didn’t matter. It felt like New York was drifting away, its demonstrations familiar, its conclusions forgone. Since coming here, I’d adored the bleak dispirited cinemas, streets sweetly nourished by perfumes of uptown matrons. But the time was coming. The city had grown wary of sustaining the ambitions it had cultivated in the young people who’d come to it. Notice was being given—local scrip would no longer be redeemable.

Later, after the school year had worn to a close and the yeshiva students all went off to lives they’d be living thereafter, I quit both jobs. I left my roommate to keep the apartment for himself and took a Greyhound cross-country, to California, then flew to Hawaii. I’d only the vaguest plans, but the idea of getting a job somewhere in the tropical line offered the least resistance to castaway fantasies I’d semi-nursed since watching Swiss Family Robinson on tv as a kid. Eventually I got hired by a scuba and fishing shop on a harbor on the outskirts of Kailua-Kona, on the Big Island. South Pacific trades wafted from the ocean, criss-crossing lava fields and a too-ambitious parking lot that belonged to the strip-mallish conglomeration of buildings where I worked. Here I could write for long stretches, interrupted only by the few straggling tourists looking for recommendations on tuna and marlin rigs or cheap snorkel gear for the kids.

My novel of Thomas Leroix, the disaffected Confederate creature, was almost a thousand pages by this time. But still no closer to being finished, I was afraid. We’d been together, the obsessive, reclusive Leroix and I, two or three years, I was his eager valet, carrying his hat and dueling pistols. Responsible for his dinners and despairs. We’d both managed to find ourselves in unexpected precincts—him in Kansas, me in Kona—looking for denouement. In my Ali’i Drive apartment, geckos scaled the screens like mountain climbers, munching palmetto bugs, and I woke no roommate, disturbed no lovers in adjoining rooms. Only the nocturnal geckos were there to regard me—their skeptical eyes and chops that would have munched me too if they could.

Tropical nights, fragrant of banana plants, oceans, night-blooming jasmine, came and went in splendid uniformity. It rained only at night, so it seemed, great sky-cleansing tempests hammering the tin roofs of nearby houses. Then the mornings reposed in rainless luxury, the lava fields dried before the sun was fully risen. New York, half a world away, never did exist in Kailua-Kona’s consciousness, I thought. The islands were geological in reasoning, massive active volcanos plunging seven thousand feet to the bottom of the Pacific, and pressed no immediate demands upon a writer, culturally speaking, as Brooklyn had. The images I was trying to summon—the Civil War’s splurge of carnage, Thomas Leroix’s regiment trudging along a mountain ridge, half-buried corpses exposed by the rain—had no analog in the lava and banyan and coconut palms.

Stranded upon a shore far from the East River, staring out to another sea, I could work with little mental interruption. “God keep me from ever completing anything,” says Ishmael/Melville in Moby-Dick. “This whole book is but a draught – nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!” Aye, but the least one is ever offered is a draft of a life, a draft of a draft, before the words drift away upon the trades.

You might be interested in

Sojourning down American Highways via Thumb

It was a time of nicknames.

The Centaur’s skin, all moon-grained in an idle mirrorreminds him of an ailing heartdrawn out in sundry mortal quests.

And you whose face so famously winces . . .

Reconsidering the supreme stylist’s status in the canon.

I

n September of 2013, the Library of America issued canonical editions of John Updike’s collected stories, adding to the slim stand-alone volume, Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu, published three years earlier. Then in 2018 and 2020 respectively, the Library put out Updike’s novels (Selected Novels 59-65, and Selected Novels 68-75). With the exception of Hub Fans, of major American poets/writers in our lifetimes, John Ashbery, Phillip Roth, Saul Bellow, all had beat Updike in admission to the Library’s pantheon. Perhaps the omission was related to publishing rights or some other ungratifyingly arcane matter, but one might also have suspected a snub. Nevertheless, it is gratifying to find Updike, while celebrated in life as one of the most nuanced chroniclers of his generation, finally getting a seat at the afterlife-accredited writers table. Updike’s working life as a writer extended roughly from 1954, when he graduated Harvard College and his stories started appearing in the New Yorker, to the early twenty-first century, when the last novel, Terrorist, was published. Along the way came novels, stories, poetry, critical essays, personal reminiscences, incidental bits and pieces, in an unrelieved torrent, more words than a reader could possibly hope to keep up with in a lifetime of summer reading. For some, this was not a sign of a brilliant prolificness, but of post-war work ethic of a Pennsylvania autodidact, or a logorrheic pathology. Among prominent practitioners in the lit-crit business, David Foster Wallace, James Wood, Harold Bloom, had taken a rather dim view of Updike’s oeuvre. His facility, versatility, subject matter, were somehow signs of suspect gifts, like those of a speedy shortstop who hits fifteen or twenty home runs a season. Bloom included only Witches of Eastwick, surely a minor if popular novel, in his grab-bag compendium of canonization-worthy world literature, The Western Cannon, tacitly damning Updike with faint praise. Wood was even more dismissive. “If one is always blearily swimming towards the raison d’être of these stories, it is largely the prose which is slowing one’s passage. The sentences have an essayistic saunter; the language lifts itself up on pretty hydraulics, and hovers slightly above its subjects, generally a little too accomplished and a little too abstract.” Yet even as Updike’s immense powers inevitably tailed off (Terrorist is an attempt to graft the usual obsessions of sex and domestic roiling onto the contemporary scene, and almost every page has something clumsy and essentially witless in it), and exposed him as occasionally limited in emotional and thematic range, the true gift—of generosity, sly love, his canny aptitude at translating shapes and sounds to metaphor—remained, if you ask me, pulsating. Despite its essential miscalculation, in Terrorist we still encounter throwaway nuggets that approach prime Updike. “His grandfather had shed all religion in the New World, putting all faith in a revolutionized society, a world where the powerful could no longer rule through superstition, where food on the table, decent housing and shelter, replaced the untrustworthy promises of an unseen God.” It isn’t, as Wood suggests, dutiful prose, but a pulse that simultaneously contracts and expands through the prose like electric current. Updike’s bracing last poems, collected in Endpoint, are mostly shorn of fancy writing, and present lives that ignite and flare out in fractions of a second, the way lives do. The poems are existential missives, child-like in the declarative affection that animated his fiction at its best.

They’ve been in my fiction, both now dead,

Peggy just recently, long stricken (like

my grandma) with Parkinson’s disease.

But what a peppy knockout Peggy was!—

cheerleader, hockey star, May Queen, RN.

Pigtailed in kindergarten, she caught my mother’s

eye, but she was too much girl for me….

Dear friends of childhood, classmates, thank you,

scant hundred of you, for providing a

sufficiency of human types: beauty,

bully, hanger-on, natural,

twin, and fatso—

or, regarding his own life and posterity:

A life poured into words—apparent waste

intended to preserve the thing consumed.

For who, in that unthinkable future

when I am dead, will read?

Library of America has placed its bets that readers born in the latter twentieth and early twenty-first century will, finding sentences, characters, stories, worthy of their attention; that the ancient Protestant steeples, putting greens and suburbanites’ messy extra-marital couplings will continue to resonate in the America of, say, 2045.

The past recedes into a vanishing point. Some authors, almost before the body goes cold, are relegated to ash heaps of their time. I for one am frequently puzzled how readers of the mid-nineteenth century could have found much merit in the works of some of its most beloved writers. Longfellow, William Gilmore Simms, even Harriet Beecher Stowe seem to me tediously sentimental, superficial, possessing a sclerotic mannerliness that seldom transcends the prose conventions their own era. It can happen to the best of ‘em, I know. Recently I purchased Library of America’s edition of Henry James’ Notes of a Son and Brother, and A Small Boy and Others, which for decades had been available only in backroom library copies, or on the shelves of obsessive Jamesians. I worship the meticulously witnessed The Bostonians, Portrait of a Lady, Daisy Miller, and shorter tales (What Maisie Knew, Aspern Papers…), but struggled mightily to find a clear path into the late period James of A Small Boy. Its tics, throat clearings and genealogical obsessions seemed to coerce the reader into joining James in wandering the labyrinths of his own mind, or that of the amanuensis as he dictated in his cottage in Kent, with nary a helpful guide in sight. Likewise, one wonders if some of Updike’s novels might belong to the past’s un-resonant designs, the literary equivalent of a Dodge Dart, say: in the years between his graduation from Harvard and the post 9/11 collapse of politically heterogeneous but coherent-seeming America, Updike—increasingly, unfashionably, white, privileged, male—had become at risk of becoming an awkward counter to America’s twenty-first century polyglot growth spurt—not just in the academy but in popular imagination. His tales, like those of John Cheever or John O’Hara or Sinclair Lewis of earlier generations, might be read simply as the outrageous hijinks of a vanished tribe. Moreover, Updike’s fixations on the anatomical, his unrelieved male gaze, and tacit endorsement of social coherence over the wildly, vividly anarchic, were unfashionable even at their peak, as if he were the privileged passive recipient of all that 60s and 70s free love and protesting and cultural ferment, without himself bothering to make much contribution to it. Compared to, say, Mailer’s boisterous chronicling of his ramblings with Robert Lowell in midst of march on the Pentagon protests in The Armies of the Night, Updike’s tales of Joan and Richard Maple marching in a 60s Boston protest while their marriage dissolves, or his patronizing description of the African-American radical, Skeeter, in Rabbit Redux, as “finely made electric toy,” can be read as an enshrining of privileged liberal assumptions, valuing irony over earnestness, preserving the status quo through dabbling in radical chic.

Sometimes it’s hard to discern the line between Updike and his alter-egos. We’re not sure whose mind we’re in, or what side we’re supposed to take. When Rabbit declares, “‘I hate [taking the bus]… It stinks of Negroes,’” one wonders if one is supposed to reel in disgust at Rabbit’s casual racism, or nod in assent. Pleasure or pain can provoke —or barely elicit moral upheaval. When Jill Pendleton, the runaway teenager living with Rabbit and Skeeter, dies in a fire, it hardly registers an emotional tremor. A cop asks if she was a loved one, and Rabbit answers, “‘Not exactly.’” Her erotic value, her life, obliterated, Rabbit moves on. Her carnality may have been splendid, but once it’s gone, the memory leaves little emotional trace. One wonders if this is the chilly flip side of what David Foster Wallace meant when he claimed, “that for the young educated adults of the 60’s and 70’s, for whom the ultimate horror was the hypocritical conformity and repression of their own parents’ generation, Mr. Updike’s evocation of the libidinous self appeared redemptive and even heroic”?

It’s hardly Rabbit’s greatest moment, but Updike resists easy summing up, and Mr Wallace’s faint grumbling strikes one as an adolescent fantasy of tearing down daddy’s house. We root for Rabbit as a heroic figure, flawed but decent in a modern semi-corrupt way. Halfway decent people can be profound assholes. Assholes can have their little moments of redemption. But Updike often refuses to give easy ways out. In Couples, the Rabbit quartet, The Centaur, or a parcel of other novels and stories, Updike’s America never settles into convenient taxonomies. We have to do the work of separating the characters from the books. But—and this is what separates Updike from lesser mortals—in sentence after sentence, his prose enlists us in rapturous delight in the ongoing project of American democracy. Regardless of what you think of Rabbit’s boorishness, he shares with his creator a multi-sensorial observational quality, and his observations, filtered through a writerly consciousness, at least partly atone for a great appetitive, American-style sense of entitlement. As with Thoreau’s observations of the skirmishes of his beloved ants at Walden, we get a sense of Updike carefully superintending his characters’ behaviors, relishing them punching it out in a not-always accommodating world. In their corner, he nudges them onward.

It’s also worth noting that, although Updike’s books range in scope, geographically speaking, so many of his characters—the golfers, ministers, carpenters, professorial types, warlocks, car salesmen—toil in familiar Updike real estate: the cloistered suburbs of the Northeast. The suburbs often get a bad rap from denizens of urban, hipper precincts; but in Updike’s hands, they function as literary metaphor, and one of his more tantalizingly realized characters. Even suburban weather can be characteristic, signaling the presence of god, or a shadowed shabby-picturesque domestic doom: “Autumn is starting to show its underside: out of low clouds like a row of torn mattresses a gray rain is knocking the leaves off one of the trees. That lonely old maple behind the Chuck Wagon across Route 111.…” On these streets, we seek, along with the author, links between the dismal and sublime, the sacred and profane. Fallen or otherwise, such suburban paradises are the loci of eternal drama. Worn-in, worn-out lives often stir and peter out not in existential angst, but in a low-level worriedness. Sunny vistas contain essences of mortality: bodily disintegration is dissonantly unforeseen in the midst of the grassy, glitzy bounty.

Part of being a Big Man (perhaps less so, Woman) Writer is that you’re expected to be a colossus, not merely a reporter of the minutia of the passing parade. Melville, Mailer, Roth, Bellow, Faulkner, bestriding the empire, rip through whole towns and countries with insatiable appetites, their tomes rippling with Big Themes. “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme,” Melville says. “No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be who have tried it.” In his way Updike was indeed trying to write a mighty book on the flea, reporting minutia from the neighborhoods. As a would-be Big Man of American literature, however, his stature rests not upon a singular novel or two, but, like Balzac, upon a collected oeuvre spanning more than half a century. His individual books, with perhaps the exceptions of Rabbit is Rich or Rabbit at Rest, are not tour de forces, but carefully observed tableaus, sociologically and culturally engorged, bursting at the margins, but whaling trips are not undertaken, wars aren’t fought, there are no epic cross-country journeys of self-discovery. The Bigness comes from an accretion of detail that over fifty years develops into an American La Comédie humaine. Several years ago I reread the four Rabbit novels (and one short postscript included in Licks of Love, a short story collection) over the course of a couple months. I’d read all of them years before, but in a haphazard, rather casual manner. The experience of reading them in sequence, however, left me reeling: starting in 1960 with Rabbit, Run, Updike checked in with Rabbit roughly every decade, taking him from a young man who, like the post-high school hanger-on in Richard Linklatter’s in Dazed and Confused, dimly senses his own limitations, aware that he’s living a prolonged afterlife, but holds to it as long as he can because he knows, somewhere in his American soul, that that’s all his life has to offer, to an adulthood of some unexpected material and spiritual attainment, a self-indulgent but humbled oldster, hustling to keep up on a basketball court. Rabbit’s individual experiences are greater than their sum, as perhaps all of ours will be. He dreams, plots, feuds, parents disastrously, loves perhaps slightly less disastrously, plays some golf, hawks cars, goes somewhere but not where he intended. But the books are greater than their parts. To read them quickly is to witness the increments of a life, days accumulating as years, fads, fashions, politics, passing so quickly that you hardly recognize a summary is in the works.

Mr Wallace criticized Updike for his obsessions with sex and mortality, but these are the obsessions of the flesh—organic modalities with which we cling to existence. The usual bourgeois trappings (all those Chuck Wagons) may eventually eradicate the enduring maple, but in the meantime (that is, our existence) we find our way, coming to terms with tensions of earthly strife and strive. Updike’s shopping malls, beaches, afternoon football games, like James Agee’s hissing sprinklers on summer lawns, or Wallace Stevens’ “coffee and oranges in a sunny chair,” provided context from the Eisenhower administration through the Obama; it seems, however, a writer’s observational powers, like that of space telescopes, are trained upon a fixed quadrant of the sky. Writers serve their times and are served by them, and in their deaths take the era with them (Updike died of lung cancer in 2009). I have no doubt that, had he been born in 1530, Updike would have turned out perfectly formed sonnets, but, as a conscientious, orderly writer, perhaps would have been less fine a chronicler of near-mid-twenty-first century’s hectic mayhem. Still, the prose remains in its equipoise and aptitude, elevating the quotidian to the noble. “The shade of the brick pavement under the streetlamp was the purple of wine dregs,” a character in Couples observes on a late-night walk. “Piet noticed a small round bug scurrying along a crevice: a citizen out late, seen from a steeple. No voice to call him home. Motherless. Fatherless.” On Updikean turf, bugs and nocturnal wanderers alike are furnished a home

You might be interested in

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

Sojourning down American Highways via Thumb

The Klan in my backyard.

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

The porn star & the president. One nation’s not quite love story.

There’s an unruly tag poking out from behind the black bra strap, between the defined blades of her shoulders, and she bounces up onto the stage, two, three, wiping down the stripper pole like a scrub nurse. In one gravity defying motion, she—brunette, pimples, ponytail—shimmies up the pole, thighs like a vice, she’s high, now impossibly higher, bumping against the ceiling, smiling down upon us like a winged seraph. Then comes slamming down—a firefighter, or a loser in a country-fair greased pole contest—as the amplified music, an unholy alliance of Classic Rock and nuevo synth, beats beneath the voice of the MC. The crowd, vaguely piqued, vaguely under- eroticized, waves two-dollar bills, she tucks them in her thong and scampers off stage, met by the club’s handler with a towel and helping hand.

It’s Stormy Daniels night at TJ’s Showcase in Scarborough, Maine, part of her national Make America Horney Again tour, and locals pack the place. I’ve been here since eight, it’s ten, no ten thirty, still no sign of Stormy, still a panoply of young women in underwear, fishnets, as variously, vigorously tattooed as Queequeg, chatting up the patrons (“clients”) for twenty-five buck (plus tip) dances. There’s a milling of regulars who’ve come out on a Thursday night to share the room’s dwindling oxygen and the dancers’ singular perfume. My legs are getting stiff from not budging from the position I’ve staked out at the bar, my budget’s wearing thin from the seven dollar beers, and I turn to reading a biography of Mark Twain I’ve been trying to finish for days. I came to bear witness to what I thought could develop into a blood feud between reds and blues, a tableau of the country’s polemical woes played out in the unlikeliest of venues, but nothing of the sort seems to be developing. A couple days after tonight I read that indeed there’ve been sign-carrying Stormy supporters rallying outside other clubs on the tour, but if any liberals like me have shown up tonight to be sanctified in Stormy’s presence, there’s no evidence of it.

There’s not a single MAGA hat in sight either, no hoots of derision, no talk of impeachment or insurrection, no storming of the barricades. As meme measuring, my reportage appears a bust. Still—by ten thirty the place is filling. Some middle-aged guys who look like they’re back from a day’s charter fishing expedition congregate by the bar, chatting up the dancers, who sense money in the water. A posse of twenty-somethings shuffles in in matching t-shirts: a bachelor party of decent seeming guys on a mission. A smattering of housewives and househusbands on risqué date night, it looks like, extend bills toward a new dancer on stage, who accepts them between her breasts with a shrug and grin before slipping away. In light of Metoo, such congregational illusions, sustained by alcohol, perfume and suspension of disbelief, can seem a relic of the frathouse, retrograde male hegemony, and casual Trumpian indifference to any but the most superficial, utilitarian aspects of another’s existence. Pure transaction. But you can’t help thinking there’s also an element of high theatricality here, gymnastic attainment that might just be worth the price of admission. It’s genuine showbiz razzmatazz of a sort—purveying desire and desirousness as spectacle. The dancers are hustling entrepreneurs, making a living American style, winking at the fakery of the apparatus, like magicians with a twinkle in their eye before they saw the assistant in half.

I try interviewing people. The proprietor of a restaurant a few towns away tells me he just wandered in, and is miffed at having to pay ten bucks over the usual ten for admission. Another guy, Sean—late twenties, goatee, with the look of a recently retired decathlete—explains he’s here because he “misses someone.” The Someone, an ex- in Portland, dumped him a few months ago. In the history of burlesque and can-can and ankle shows there must be more than sufficient number of lonely guys who seek comfort in dancers and can-can girls to populate several large midwestern metropolises, but if you ask me it’s a poor bet that TJ’s Showcase will assuage the heartache of any of them; but Sean’s got a plausible schtick, a patter that he claims is effective in securing attention: the genuineness of his feeling, he tells me, gets him a discount on lap dances.

Dancers, he says, genuinely come to love him, and he wields a slick narrative.

Maybe so, I nod, trying to decipher cabalistic meaning in the disclosure. But then, apropos of nothing it seems, he tells me that maybe a caucasian couldn’t totally understand what he’s getting at. The position of a white man in America is always one of privilege, he says, leaning in for emphasis. Sean is African American. I’m not. But I believe in my perhaps privileged way that the commonality of human spirit trumps identity politics most of the time, and Sean’s is a diversion that has strayed from the point that we manipulate that emotion in an attempt to recapture something genuine. I scribble notes on my hand (my notebook having been impounded at the door), and, feeling emboldened, broach the subject of Trump. Sean declines the bait. He’s here for a good time. Not just forget his Portland sweetheart, I deduce, but in some way forget what it means to be black in America under the administration of an avowed, unrepentant bigot. Perhaps he’s right: the right to dwell for a moment in the half life of an American strip club is a way of getting out from under oppression in love or race.

I look around for more potential interviewees, when at once the crowd grows remarkably still. And here she is.

Collectively we hold our breath. We regard her with an awe afforded a lesser order deity but deity nonetheless. Stormy. Over the sound system, the disembodied MC proclaims, Stormy Daniels, Stormy Daniels, Stormy Daniels, like she’s a pro wrestler, or one of those trucks with enormous wheels that drives over a row of twenty Volkswagens. It’s the default mode of marketing, I think, denoting something transcendental, the pushy imperatives of our time. Her entrance music is Steve Miller’s Abracadabra (Reach out and grab ya—). She bounces up on stage wearing black tails, a jauntily bespangled top hat, which gets tossed to a lucky fan. She lifts her knees like a majorette, shakes her leonine mane, flashes a perfect smile, and gets down to business. In fifteen seconds her shirt’s off, twenty seconds tops. With sisterly camaraderie, she goes for the women flashing bills at her. If I were to guess, I’d guess that Stormy understands the construction of comedy as well as any stand-up in the country, tragedy-as-farce is her stock-in-trade.

What must she think of the fun-house mirror of her life? I wonder. In the liminal realm of politics and sex, does she take measure of how others see her? What would-be caricatures of herself threaten to subsume her? Raised in dumpy exburbs outside Baton Rouge, a teenage denizen of shopping plazas and incandescent-lit parking lots, slurping chocolate shakes in cars, you’d think she’d make an unlikely redeemer of our collective national nightmare. But she’s what we’ve received, take her for her all in all. Her seeming middling conventionality is what’s so thrilling. She’s an ardent and very good horseback rider, one learns, good mother, soon-to-be-divorced wife, savvy business operator, producer and writer and director of porn films of a certain quality. She considered a run for Senate, as a Republican no less. By all accounts, she’s defining herself as she wishes, and comes across as wholesome, a soccer mom with a g-string under a sensible skirt. She won’t be pushed into being a redeemer on anyone else’s terms.

Now, dancing, shimmying, working the spotlight, she spies, stage right, a guy with a goatee, dressed in Stormy drag, wig, miniskirt, inflated balloons for breasts. A burlesque of burlesque. Catching his eye, she seems enlivened, gratified by the funhouse impersonation, and kneels down to him, massaging her slightly more authentic breasts against his. The faux-Stormy’s girlfriend’s fingers glide along the real Stormy’s arms, as if trying to discern the difference. Then it’s over practically before it’s started. Stormy simulates auto-erotic pleasure, hoists her breasts, waves to the crowd, and makes her exit, scooping up stray bills along the way, making sure no money is left on the table. Hefty security guys hustle her off stage. And we, collectively, regain our breath, return to our beers, and wonder exactly what we’ve just witnessed.

I relinquish my spot at the bar, trying to see if I can beat out the Times for a revelatory quote at the meet-and-greet (an additional fee), but my legs are tired, it’s late, and a No Comment would make a depressingly intrusive coda to the night’s oddly introspective visions. I overhear the faux- Stormy say: “No matter what else happens to me, at least I’ll always have that.” Maybe that’s as close as I’m going to get for a quote, and maybe that’s what I have too. I glance at the notes scrawled on my hand (“Abracadabra,” “Fred Astaire,” “Miss Someone”), and return to the Mark Twain, re-immersing myself in the nineteenth century’s own scandal and disgrace. Another dancer is strutting across the stage now, and the republic of Lincoln, Jefferson, Frederick Douglass, still holds, and, with Stormy now at its disputatious center, we still believe, despite the odds, in the rowdy, quarrelsome, shambolic spirit of America.

You might be interested in

Charles Manson and his followers settled in at the Spahn Ranch, in Los Angeles County, in the summer of 1968.

In the spring of 2002, college art student Luke Helder set out to trace a Smiley Face pattern over the

The Klan in my backyard.

It was a time of nicknames.

Considering icons of different music worlds: two eulogies

Maybe rewrite history and David Cassidy shows up late for the Partridge Family audition, stoned, hair plastered to his skull, so the next guy, Walt Strohman or someone, ends up Keith Partridge, and somewhere down the line Walt runs for President, drives into North Korea with a USA flag pin in his lapel. David Cassidy, well, let’s just say he joins the Peace Corps, gets a corporate gig, divorces, bangs up his knee in a hang-gliding incident, spirals sideways, slurping solo appletinis at Olive Garden. You get the idea.

But the moment David Cassidy became Keith Partridge, he became fixed as Keith Partridge till the day he died, like Elvis kept on having to be Elvis, and Chaplin couldn’t stop being the Tramp, penguin walking even unto Swiss exile. Twenty years old when he got the job, David-cum-Keith lived blessedly in a California cul-de-sac (I think), riding to gigs on the funky Mondrian Partridge Family bus.

The bus was made for Keith—a proxy for America trying to outpace the Eisenhower suit, black-and-white tv. It’s hard to remember, but buses at one time were conveyances of transcendence. You know, not just sharing a smoke with a sad-sack in worn-out shoes, but Ken Kesey, Greyhounds to Montgomery, Fathead Newman blowing sax on the chitin circuit. To be sure, the Partridge Family was commodified, homogenized, Keith the epitomized product, the bus doubtless a product of much corporate dithering, but when the Partridge Family first aired, September, 1970, as school kids were getting back from summer vacations, maybe a school bus wasn’t just a school bus, it could be like an express ride to Valhalla. At the top of our lungs, my grade school friends and I sangshouted “I Think I Love You,” maybe it was, or “I Can Feel Your Heartbeat” or any of the catchy leave-nothing-to-chance Wrecking Crew tunes coming through the static on those waning summer days. David Cassidy/Keith Partridge with his earnest sloe eyes and hair like a fashion-forward Jesus’ had come to carry us to salvation. We were ready, willing, rapturous.

Grant Hart, songwriter/drummer in the seminal punk outfit, Hüsker Dü, died a week before David Cassidy—in comparative obscurity. I didn’t even learn about his death (liver cancer, Hepatitis C) till months after the fact. But like David’s, Grant Hart’s life would be summed up from a brief intensely packed period in his twenties. From 1979 to 1987 Grant sang from behind the kit like Gene Krupa and Judy Garland on everything, bare feet pumping the bass pedals, hair whipping off halos of sweat. Hüsker Dü had aspired to be punk rock’s answer to the Beatles, and succeeded to the extent that the band was once interviewed by Joan Rivers; but they never became the Beatles, or U2 or Culture Club for that matter. After the band’s inevitable breakup in 87 Grant, for all his vividness, became a cautionary tale, living a mashup afterlife of semi-addiction, puttering with classic cars, painting, sliding in and out of the alternative rock scene, releasing an underappreciated album here and there. Maybe some of us will always be ourselves, vectors of our genes’ power over us, while others are irrevocably exponents of chance. There was probably no alternative life for Grant Hart. Winning the lottery, a hang gliding incident, wouldn’t have knocked him off the course he was on.

People often assume, I think, America was pretty radically made over in the time between the cancellation of the Partridge Family tv show in 74 and the release of Hüsker Dü’s first album (Land Speed Record) in 81. But who knows, maybe things didn’t change that much. In the early 70s, tuning in Cronkite, helicopters cruising over Vietnam jungle, the choppers’ whack-whack contrasting to my bicycle chain’s metallic whirl as I pumped across neighbors’ lawns in suburban Massachusetts, optimism was still the default American mode. In time Vietnam ebbed, the choppers lifted off the embassy roof, and Reagan’s sunshiny jingoism creeped into the living room, the bedroom, the boardroom. USA! USA! Hüsker Dü was only one of the bands that signaled the 80s flowering angst, twists of irony, a counter to the optative mood, but the band also germinated its own sense of precarious hopefulness. Listen to “Celebrated Summer”—and tell me it doesn’t knock you into a state of anguished ecstasy.

You don’t have to be a soothsayer to discern the consistent currents flowing beneath changeable surfaces. It was the 80s. I was exploring different directions in music, literature, movies—chasing the highbrow in a suburban middlebrow way. I graduated college, hitchhiked around, moved to Hawaii to complete the novel I’d been working on, wrote some poetry, moved to Brooklyn. Sometime in the midst of this perambulating, I scrounged tickets for a Hüsker Dü show in West Hartford, Connecticut. The show was toward the end of the band’s run, but on stage, pounding his drums, Grant didn’t appear to be running out of steam at all. He wailed “Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill,” “Don’t Want to Know if You Are Lonely,” full-throatedly, mop hair whirling. I pogo’d like crazy in the front row. The crowd sang along in tribal solidarity and, so it improbably seems, joy. It reminds me now, in David Cassidy’s and Grant Hart’s coincidentally linked deaths, how we did sing in our collective euphoria, preteens and punks, without exclusionary pretense, and lived for those moments of pure aural bliss, living for the tunes, as if no other utterance could possibly add to the divine nonsense of being.

You might be interested in

Sojourning down American Highways via Thumb

Compulsory Patriotism: The National Anthem as Sports Ritual

It was a time of nicknames.

A brief history of being young & adrift in 80s New York.